|

THE CLIMBER'S CLUB JOURNAL London, England 1903 (Vol. V. No. 20, pages 159-167)

MOUNTAINEERING IN MEXICO.

By Oscar Eckenstein.

The higher Mexican mountains have, from the mountaineering point of view, one charm which nearly all mountains lack; and if that charm could only be extended to other mountainous districts, the lot of the mountaineer would indeed be a happy one. I refer to the practical certainty of the weather. There is a dry season, and there is a wet season. During the dry season there may be one, or even two bad days, but that is only in exceptional years. During the wet season (our summer and early autumn) on the other hand, the weather is always more or less unsettled, and storms are frequent. During all our climbing in Mexico (December 1900, to May, 1901,) we were not once troubled by bad weather. Indeed, on our Volcan de Colima excursion, wet weather would have been an advantage.

Not much information is to be found in English or foreign mountaineering literature on the subject of Mexico. There is an account of the second ascent of Iztaccihuatl by Mr. I. R. Whitehouse, in the Alpine Journal, Vol. XV., pages 268-272, and there is an account of some different ascents by Mr. A. R. Hamilton, in the same publication, Vol. XVIII., pages 456-461. A few notes in foreign publications are practically only repetitions of some of the same information. So that when my friend, Mr. E. A. Crowley, who happened at the time to be in Mexico, invited me to join him in some mountaineering there, I had only very vague ideas as to the possibilities of the country in that respect. When I arrived (December 1900), I found that he hardly possessed any more information than I did; the inhabitants generally seemed to take no interest in the higher mountains, and knew little to nothing about them. The only exception to this rule that we came across was Señor Ezequiel Ordoñez, of the State Geological Survey, who not only took a keen interest in the mountains of his country, and had ascended a number of them (including Iztaccihuatl), but who very kindly assisted us in every way, and did much to make our way smooth for us.

The chief mountains of Mexico are:—

1 Old survey. The mountain is frequently misnamed Orizaba, which is the name of a province and its chief town. Citlatepetl is not in the province, but is conspicuously visible from the town. 2 New survey. Determinations I made were in very close agreement. 3 This name is used rather indiscriminately. On the new map it is applied to the point 4740 (the group of towers which I ascended, January 22nd, 1901), but it is popularly applied to the south end of the snow ridge, which can hardly be considered a summit. Certainly "Feet" of the "White Lady," as seen from Mexico City, would appear to be formed by the end of the snow ridge. 4 Old survey. 5 Estimate. Approximate. 6 Boiling point determination. Old survey, 4330 metres. 7 Boiling point determination. 8 Height determined by the old survey. When we saw the mountain it must have been about 100 metres lower. It varies a good deal.

Our first expedition was to Iztaccihuatl, a noble mass, visible from Mexico City, and the only one in the country with well-developed glaciers on it. An additional inducement to visit it was the statement of Mr. Whitehouse, that "The arête we climbed would appear to be the only practical route to the summit. . . . I doubt if it would be possible to reach the summit or summits by any other route than the one we took, as on all sides, as far as I could discover, there were sheer ice walls and precipices."[1] As far as we could ascertain the main summit had only been ascended four times, each time by the route taken on the first ascent, and the other summits had not been ascended. Particulars of the new expeditions we made have already been published in the Climbers' Club Journal, Vol. III., pages 199 and 200). One interesting point was our speed in ascending, which was a good deal greater than any hitherto recorded at similar heights.[2] Thus in our expedition of January 28th, our rate of ascent (heights between 13,717 and 17, 343 feet), stops excluded, was 907 feet per hour, and stops included, 691 feet per hour; and this included some difficult and laborious ice work. The easier part, that from our camp to the col, which involved long traversing and the ascent of a small icefall, took just 2 hours; the difference of level being 2687 feet. Another point of interest was, that in my expedition of January 22nd, I came across a cavern, from 80 to 100 feet high, in a rock face under a glacier, which was filled with vast icicles, both of the stalagmitic and of the stalactitic class; many of them extended from roof to floor. In our expedition of January 24th, we found some of the worst walking we had ever encountered. It was a nearly level snowfield, with a smooth, unbroken surface. When we ascended it in the early morning the walking was excellent. But on our way back, when the surface had become softened, it revealed its most objectionable character. It had been formed out of ice avalanche debris, covered by a thin layer of snow which filled up the interstices. And walking over, or I may almost say through, it was a most joint-wrenching business.

Our next trip was to the Colima district. Nineteen hours by rail from Mexico City took us to Guadalajara, and then we had two days by diligence to Zapotlan, the town nearest the mountains. At Zapotlan there is a meteorological observatory, where records of the eruptions of the volcano are also kept. This volcano, the Volcan de Colima, is said to be the most active one on the Continent, a reputation which I am not prepared to dispute. The neighbouring mountain mass, the Nevado de Colima, has two summits situated approximately N.E. and S.W. of each other; we did not know whether either had been ascended, or which was the higher. Three days of rather rough travelling from Zapotlan took us to a hollow, about 12,400 feet high, and open to the north, enclosed by a sort of horseshoe formed by the Nevado ridges, and here we camped for a few days. On March 3rd we scrambled up the very broken up gully (chiefly rough scree and snow, also a little rock) coming down from the pass between the two summits. It took us 2 h. 5 m. to reach the pass (4,204 metres = 13,793 feet). From here a very jagged rock ridge, with numerous towers, leads up to the N.E. summit. The climbing was quite easy. From the pass to the top took 55 minutes; but then we climbed all the towers on the way. We found, much to our satisfaction, that our summit was a virgin one; but that satisfaction was somewhat tempered by the fact that the S.W. summit, was undoubtedly higher. Later on we ascended the S.W. summit, it was merely a scramble, and it had evidently been ascended before. We next determined to go on to the volcano, and ascend it if possible; it is some distance south of the Nevado. The approach to it was attended with much difficulty; water was exceedingly scarce, and we had to cut our way through chaparral. In two days we reached the crest of the ridge immediately to the north of, and facing, the volcano, and here we stopped for some 24 hours (height about 11,600 feet).

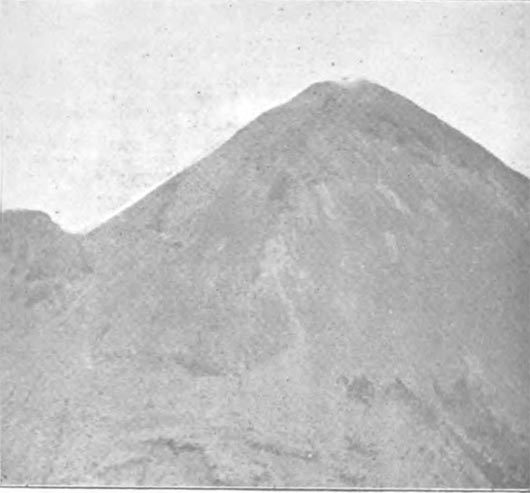

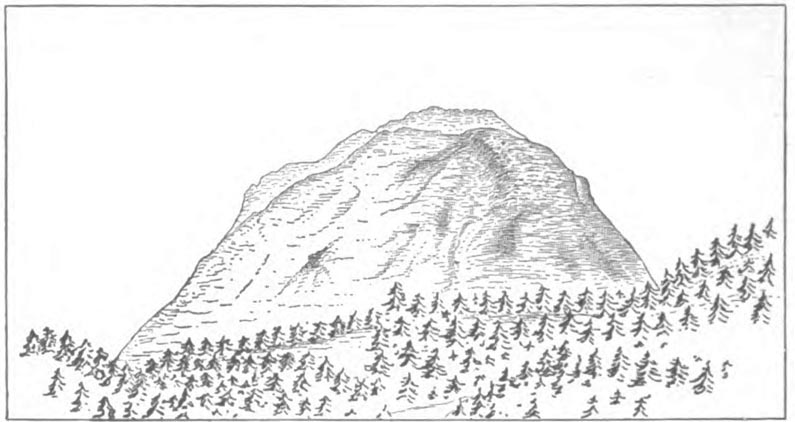

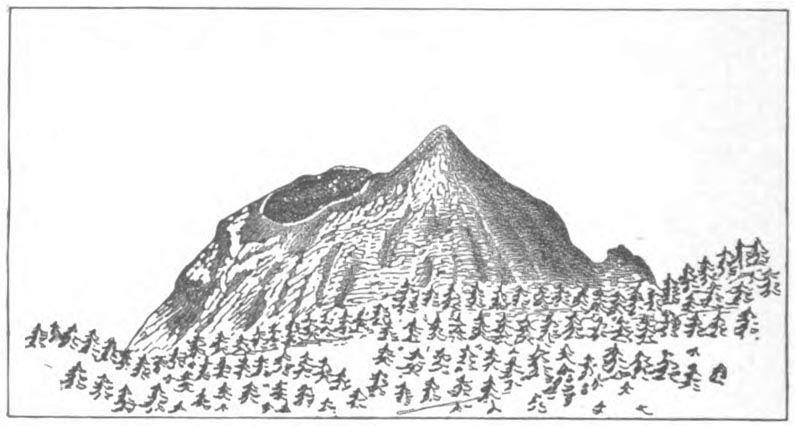

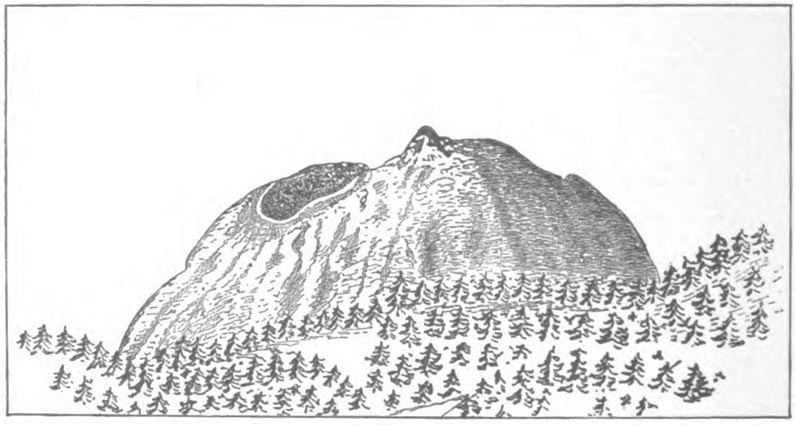

During this time there were over a dozen eruptions, and the earlier part of one of them I photographed (4 p.m., March 7th, 1901); these photographs are reproduced here. Figure 1 is the volcano in its quiescent state; figure 2 was taken 3 seconds after the eruption began; figures 3 to 7, at intervals of 3 seconds subsequently; and figure 8, 10 seconds after figure 7. Since the period of our visit, the volcano has been very active on several occasions, and its shape has undergone very remarkable changes. The appearance of the upper part of the mountain is well shown in figures 9, 10, and 11, which are reproductions of views taken, and very kindly sent to me by Señor Presbitero Severlo Diaz, the Director of the Zapotlan Observatory, who has published an account of the recent eruptions.[3] Figure 9 shows he appearance of the cone in December, 1902; figure 10 was taken after the eruption of March 2nd, 1903, and figure 11 after that of March 10th, 1903.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

The ascent of the volcano was clearly out of the question; it presented the cheerful alternatives of death by bombardment or by cremation.

On out other expeditions in the country we never had any difficulty in obtaining excellent men and good transport; but on this occasion we had to put up with inferior donkeys, and even more inferior men. As it was impossible to get them to go any further, we decided to send them back to Zapotlan, while we (i.e., Crowley and myself) went round the volcano, and made our way down to the south of the Mazanillo road. So we sent them off, and then started by ourselves. From our camp we should have descended at once straight down to the valley between us and the volcano (the slope was quite feasible immediately below us), but we made the mistake of traversing along the slope in an easterly direction to save height. As a result we became cut off by cliffs, and had to re-ascend and go a long way round till we could reach the edge of the lava field at the foot of the volcano. We then crossed the lava in a south-easterly direction; it was bad ground to go over, and the best description I can give of it is that it was like an icefall constructed out of volcanic debris. Fortunately we did not have much of it, and we soon reached the head of a valley, which appeared to run more or less in the desired direction. So we started down it. At first some chaparral gave us some trouble for a short distance, and then to our joy we struck a rudimentary but distinct track leading down the valley. But before long the track petered out, and so did the valley as a distinct valley, and our real troubles commenced. The ground consisted of a number of very narrow but deep ravines, filled with chaparral, and overgrown with big trees, and plenty of the latter had fallen down and were in every state of decay. In addition everything was covered with fine volcanic dust, and one's progress was attended with the formation of a thick and very irritating dust cloud. It was only with difficulty, and very slowly, that any progress at all could be made. At length, about 4 p.m., we struck a good path, which led down along the edge of a ridge, nearly in a straight direction. Down this we went for 65 minutes at a very great pace (rate of descent varying between 50 and 100 feet per minute). The path then turned sharply to the south-west and traversed along at a gentle falling gradient. We went on as long as the daylight lasted, and just as it was becoming too dark for satisfactory progress we found an open space, where we could stop and light a fire without danger of setting the whole hillside ablaze. So we lit a fire, partly for warmth and partly to keep wild animals off, til the moon rose some two hours later, and gave us sufficient light to go on by. Then we started again and at length, at 11 p.m., we reached water (there had been none the whole day), and we drank, and we drank, and we drank. Here we camped for the rest of the night. Subsequently we discovered that this spot is inhabited part of the year, and is known as the Durasno Ranch. The next morning two hours' easy walk on a good path took us to the San Marcos Hacienda, on the main road between Zapotlan and Mazanillo.

On April 3rd. we once more left Mexico City, and went by rail and tramway to Chalchicomula, the town nearest Citlaltepetl, and W.S.W. of it. We found, however, that the next five days being local and other saint's days, no transport could be obtained. Citlaltepetl is a mere scramble, and presents no special interest; its ascent is regularly made for sulphur collecting purposes. We therefore decided not to wait, and returned to Mexico City.

Our next expedition was to Toluca. The railway from Mexico City to Toluca City (72 kilometres) is a remarkable piece of engineering. Mr. Hamilton's statement, that it runs through "some of the finest scenery in the world" (Alpine Journal, Vol. XVIII., page 458), I am quite prepared to endorse. I do not know any railway which offers a finer display of scenery. From Toluca a light railway runs to Calimaya (17.7 kilometres), the village nearest the mountains. The whole mountain mass is known as the Nevado de Toluca; it consists principally of a large extinct volcano, called Xinanticatl, and there are a number of smaller hills around it. The crater of the volcano is of oval shape; there is a great gap in its eastern wall and there are two lakes in the floor of the crater. From Calimaya there is a good path to these lakes; it is about 5 1/2 hour's easy walk up to them. At these lakes we camped (height about 13,500 feet).

There are two summits on the ridge or edge of the crater, which are considerably higher than the rest, and it was rather difficult to see from our camp which was the higher of the two. The one on the north side is called El Fraile, and the one on the south side El Espinazo. On April 10th, Crowley and I determined to try El Fraile, which, however, turned out to be the lower by about 120 feet.

Starting from our camp, we worked our way up north on to the edge of the crater; the wall up which we went consisted of scree in very bad condition. We then walked along the top of the ridge over several intervening humps till we reached the foot of the rock ridge proper. This is the east ridge of El Fraile; it is broken up into a series of towers and pinnacles, up and over which we went to the summit. The ridge was very jagged, and all was climbing; but no extraordinary difficulties were met with. If desired, the difficulties can be altogether avoided, and the summit attained by leaving the ridge and traversing out on to the north face, which is mainly a scree slope. We descended by the west ridge (which gave us some easy rocks, and an interesting chimney which overhung at its lower end) till we reached the lowest point or col, and then went straight down the slopes (mainly scree) to the lakes. Times—camp to beginning of rock ridge, 1 hr. 30 m.; then to summit, 2 h. 30 m.; then to col, 25 m.; then to shore of lake, 30 m.; then to camp, 50m.

The next day, April 11th, I was rather upset in my inner works,[4] so Crowley went off by himself to El Espinazo, while I watched through my classes. From our camp he went in a S.E. direction up easy grass and scree slopes, till he reached the ridge which forms the edge of the crater, and then followed this ridge, which is easy walking till the first tower is reached. From this spot onward the ridge is very broken, with many towers and needles on it, and the rock climbing was of an advanced character. I found it very interesting to watch him as he slowly worked his way to the summit. From the summit he went down in a N.E. direction to the top of a couloir filled with snow, which reached down to the floor of the crater. He glissaded down this, and then cantered across to our camp (I had sent a horse to meet him at the lower end of the couloir). Times—camp to foot of first tower, 1 h. 10 m.; then to summit, 2 h. 45 m.; then to camp, 1 h.

All these Xinanticatl ridges had evidently and clearly not been climbed before; but both summits had been ascended previously.

Our next expedition was to Popocatapetl, which we ascended on April 17th, taking with us an American friend who was formerly on the staff of a Chicago paper. A humourous account of the expedition, written by him, has already been reproduced in the Climbers' Club Journal (Vol. III., pages 176 to 178). There is no climbing proper on this ascent, but only walking up very objectionable scree, or rather volcanic debris, lying at practically the critical angle. But coming down it is joy.

What was to me a matter of great interest on this ascent, was the fine display of nieves penitentes. This is the Spanish name—there is no English equivalent—for a very curious formation of snow and ice, but chiefly (on this occasion at least) of the latter. It consisted of flakes 2 to 4 feet high, and up to 18 inches thick and 3 feet wide at their base; these flakes were arranged in parallel rows bearing diagonally up the mountain, i.e., the rows ran up from N.E. to S.W., and the major axes of the horizontal sections of the flakes were in the same direction. The individual flakes were at an angle of about 20 to the vertical, and were leaning over to the S.W. They were not formed out of avalanche debris, but out of the snow which had fallen, in situ, and they covered a good many acres.

Most of the flakes were of pure ice, others were part ice and part snow, but none consisted of snow only. The way in which they are formed is as yet unknown. Sir W. M. Conway's theories on the subject (See Aconcagua and Tierra del Fuego, pages 65 to 70) are evidently quite wrong. I cannot help thinking that the action of the wind has something to do with their formation, but I am unable to formulate a satisfactory theory. We could see that on Citlateptl there were also nieves penitentes, but there were none on any of the other mountains we visited.

This ended our expeditions in Mexico. I may perhaps add that on all our climbs Crowley and I led alternately.

1—The easiest way is undoubtedly the one we took in descending on January 19th, and January 28th. 2—See Badminton, Mountaineering, 3rd Edition, pages 100-103. 3—"Las Ultimas Erupciones del Volcan Colima," Mexico, 1903. The views are taken from a greater distance than those taken by me. Mine were taken a point due N. of the volcano, those of Señor Diaz from a point E. of N. 4—We both had a good deal of trouble from our canned provisions on several occasions, and we gained some valuable experience on the subject. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||