|

THE WASHINGTON POST Washington, D.C., U.S.A. 26 December 1915 (page R2)

POET AND Magus Explains Magic On a Basis of Scientific Facts; Defends Yoga and Mystic Rites.

Another Who Set London Literary World Agog by Verses and Occult Exploits Stirs American Students of Mysticism by Visit Here— Rosicrucian Mysteries Revived Through His Facile Pen.

By L. F. Mines.

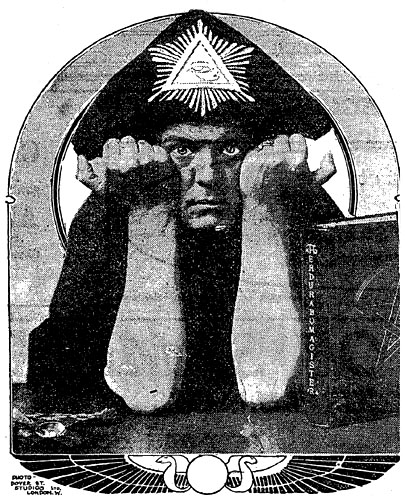

ALEISTER CROWLEY, POET AND MYSTIC.

Through the pages of history and of fiction alike glide the magi, men of miraculous knowledge, works and power, unmoved by the cares the ruffle the souls of ordinary mortals, and ever intent on the varied any mysterious tasks they have set out to accomplish. In history the few of these wonder workers that have come within the common gaze are shadowy and mythical when indeed they are not downright imposters. In fiction they are represented as impossible beings, extravagant magicians of superhuman powers. Yet always is there a strange fascination in their lives. One laughs at the very possibility of their existence, and in the same breath wonders, not a little wistfully sometimes, if such attainments may not lie within human accomplishment.

Much of the glamour which has marked the ancient magus and magician surrounds that most modern of the prophets of the concealed sanctuaries. Me. Aleister Crowley of London, whose present visit to America has awakened renewed interest of all groups of students of the occult in his lifework. But Mr. Crowley is not merely an exemplar of things occult. He is a philosopher as well as a poet into the bargain. Also, we have the word of no less competent a critic than Gilbert K. Chesterton, whose keen irony has mowed many meadows of would-be poetic blossoms, that Mr. Crowley “has always been a good poet,” and again “Mr. Crowley is a strong and genuine poet.” He is represented in the 1913 anthology of Cambridge poets.

Mysticism His Lifework.

Yet it is to the study of the unclassified or unexplained phenomena roughly grouped under the general heading “occult” that Mr. Crowley has devoted his life and his swift and graceful pen. Even his many volumes of richly harmonious verse bear evidence to the dominance of the mystic trend. Hailed as an adept by his students, an adept of the highest rank, if not the Gotama of the aeon, he is certainly the most remarkable man who ever laid hand to the almond rod of Abra Melin the Mage, or taught the secret symbols of the Brethren of the Rosy Cross. There is nothing of mystery about Mr. Crowley himself, however. He is the avowed foe of mystery-mongering and of charlatanism. Not a few of those whose claims to supernatural powers proved an easy method of lining their nests from the purses of their dupes have had their careers roughly interrupted through the activities of this English poet, who has been instrumental in sending some of the most brazen of these cheats into well-deserved punishment.

A biography—but to have the subject receive justice it should be an autobiography—of Mr. Crowley would prove far more interesting than the average modern novel, and certainly more useful if merely from the standpoint of the information it would impart. His travels in search of the secret learning jealously guarded from the profane in the tiled sanctuaries of the hidden orders of the Old World and the new have carried him twice around the globe.

Studies in the Far East.

He has traveled afoot in the desert of Sahara, where with one faithful scribe to record, he performed the astounding magical operations of Dr. Dee. Single handed he has fought the bandit tribesmen of India and China. Twice has he penetrated the forbidden fastnesses of the Tibetan plateau. With a little caravan he has made his way through unmapped regions of China, and in a dugout descended the treacherous rapids of the Red River. In Japan and Ceylon he studied at the shrine of Buddha and in a Buddhist monastery of Ceylon learned to concentrate on visions beyond the power of pen to describe. Amid the rugged mountains of Mexico he raised his mind to the Most High in quest of the Lamp of Inextinguishable Light, and in Egypt he fought the knowledge of those wise priests of old who reared pyramid and pylon and celebrated their rites in that wondrous hall at Karnak.

No Parlor Visionary.

Enough, these mystic experiences and strenuous travels, or almost any single one of them, to satisfy a man that his life was not wasted, yet they are but a few of Mr. Crowley’s explorations into the hazardous regions of the earth and the still more hazardous regions of the human consciousness. One learns with astonishment that these are but a few of his adventures, and when one reads of his Alpine and other mountain climbing exploits—he holds a few unbeaten amateur records in this field—it is easy to see that here is no parlor visionary, no rocking-chair philosopher. He is a man, a man of red blood and action, virile in everything—determined that whatever he purposes shall be accomplished. And with all this life of action and doing there stand to his credit some two score or more volumes, big and little. Even his enemies are forced to admit and admire his genius.

To the casual reader, as opposed to the student, it is description of Mr. Crowley as a magician that awakens deeper interest than all these weightier accomplishments. Can such a man don fantastic robes, take his stand in a circle scribbled about with mystic names and figures, lit with flashing lamps of strange import, and invoke or evoke, as the case may be, angels from the height or demons from the abyss? Of a truth he does, and the powers he summons seem at least to obey his command. Mr. Crowley would be the last man in the world to say that their coming proves that either angels or demons exist in the popular sense. To do so would be to cast a slur on his philosophy. Skepticism is his watchword. He warns his students not to attach philosophical validity to whatever they may see or hear in the rites of ceremonial magic. What he does say, and this applies to all his investigations, is this: “If you do certain things, certain others things happen.” Very well; and the task that Mr. Crowley has set for himself and his students is to discover the laws underlying such hitherto unexplained phenomena. Here is Mr. Crowley’s own defense of “Ceremonial Magic,” written a number of years ago.

Magic and Psychology.

“I am not concerned to deny the objective reality of all ‘magical’ phenomena: if they are illusions, they are at least as real as many unquestioned facts of daily life; and if we follow Herbert Spencer, they are at least evidence of some cause.

“Now, this fact is our base. What is the cause of my illusion of seeing a spirit in the Triangle of Art?

“Every smatterer, every expert in psychology will answer: ‘That cause lies in your brain.’

“This being true for the ordinary universe that all sense impressions are dependent on changes in the brain, we must include illusions, which are after all sense impressions as much as ‘realities’ are, in the class of phenomena dependent on brain changes.’

“Magical phenomena, however, come under a special sub class, since they are willed, and their cause is the series of ‘real’ phenomena called the operations of Ceremonial Magic.

Result of Brain Changes.

“These unusual impressions (1-5) produce unusual brain changes; hence their summary (6) is of unusual kind. Its projection back into the apparently phenomenal world is therefore unusual.

“Herein, then, consists the reality of the operations and effects of Ceremonial Magic, and I conceive that the apology is ample so far as the ‘effects’ refer only to those phenomena which appear to the magician himself, the appearance of the spirit, his conversation, possible shocks from imprudence, and so on, even to ecstacy on the one hand, and death or madness on the other. If then I say ‘the Spirit Cimieries teaches logic’ what I mean is:

“Those portions of my brain which subserve the logical faculty may be stimulated and developed by following out the processes called the invocation of Cimieries.

“And this is a purely materialistic statement. It is independent of any objective hierarchy at all. Philosophy has nothing to say, and science can only suspend judgment pending a proper and methodical investigation of the facts alleged.”

Odd Magazine of Occultism.

Five years ago the work of Mr. Crowley was brought prominently before the literary world of England through the publication called the Equinox. Issued twice a year at the equinoctial periods this magazine, in reality a volume of 300 to 500 pages was described as “the review of scientific illuminism” and the “official organ of the A.A.” The latter is defined as a society working under the leadership of certain adepts or “secret chiefs” who are nameless, but as whose spokesman Mr. Crowley acts. The issues ceased after ten numbers.

Mr. Crowley is also a high officer of the O.T.O., or Order of the Temple of the Orient, a semi-Masonic organization which flourishes in all civilised countries, especially in England and in Canada, and in the United States is represented by several lodges on the Pacific coast. This order also follows Rosicrucian lines, in that its teachings embrace occult knowledge, the magic of light, and all forms of Yoga. Its aim is to bring out of a man all that is best in him. Among other things it claims to possess the “lost” Rosicrucian secrets—the elixir of immortality, the stone of the wise and the universal medicine. A lodge of this order is in process of formation in Washington.

The instructions of the A.A., largely from the pen of Mr. Crowley, are along the lines he has followed, namely scientific skepticism. The work—this great work of these latter-day alchemists—is to find the clew to genius, the method of bringing about at will that momentous mental crisis which Prof. William James describes in his “Varieties of Religious Experience: and which the Hindus call samadhi and the Latin mystics ecstasy, or the “divine vision,” and which, as all authorities agree, transforms a very ordinary man into a very extraordinary man, indeed. Philosophically speaking, this result is the uniting of subject and object, or, to borrow from another symbolism, the development of four dimension consciousness.

Adopts Yoga Practices.

In doing this, Mr. Crowley has united a method that is unique in that it embraces all the great magical systems of the world, from ancient Egypt to the day of Dr. Dee, and even to the more recent followers of the Crucified Rose. He has adapted the systems of the East, tossing aside the chaff and threshing out the solid grain, so that his student may utilize the breathing exercises of pranayama, the accomplishment of asana, or the stilling of bodily sensation, the cultivation of mental concentration, and finally introspection. Thus, while these and other passive methods are being developed, and the student is freeing himself from the control of body and mind and is learning to control them instead, he is solving the same problem through the active magic of the West, and by ritual and ceremony, rite and ring, he seeks the same goal, the divine union.

As in a certain great order the enterer must leave all things behind him, clothes that mark rank, metal, the token of wealth and travel with breast bared to whatever sword may oppose his progress, so Mr. Crowley warns every one against the folly of mistaking names for things. He who enters this path must be free from all prejudice. Here is Mr. Crowley’s basic creed, as explained by an English writer:

Crowley’s Basic Creed.

Believe nothing till you find it out yourself.

Say not “There is a God” before you experience that there is a God.

Say not “I have a soul” before you feel that you have a soul.

You can never understand until you have experienced.

You can never experience until you get beyond reason.

In other words, know, or doubt, do not believe. “We are,” he says, “surrounded with an appearance of truth” and reason is our guide. To become part of the reason we must leave reason on one side if we would reach that place where, he sings.

“Paying no price, accepting naught, The giver and the gift are one With the receiver.”

It is true such mysticism promises much to those who persevere. It is also true that those whose feet have just entered upon this path say they have found it the hardest kind of toil. Yet, if the so great reward is really awaiting the faithful servant, is it not a temptation to try? |