|

WORLD REVIEW London, England July 1949 (pages 54-57)

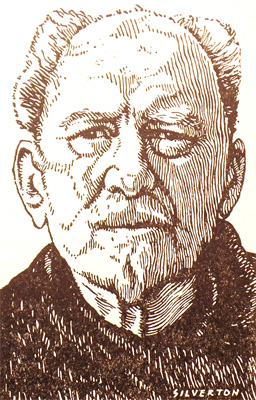

ALEISTER CROWLEY.

THE DEVIL’S CONTEMPLATIVE.

I first met Aleister Crowley when he was already old. He was living in retirement in a boarding-house on the outskirts of Hastings, a large and—to me—sombre house, standing in its own grounds, and hidden from the road by stalwart trees.

A year before, Clifford Bax had said to me: ‘You should meet Aleister Crowley. He will die soon and then you would have lost your chance.’ He added with a smile: ‘I will have him sent to London for you’, as if Aleister Crowley were some fine old vase or piece of carved ivory.

I didn’t bother Mr. Bax to pack up Crowley for me, but instead made the journey to Hastings, taking with me my friend, Rupert Gleadow, the astrologer and poet. ‘He will die soon and then you would have lost your chance,’ I said to him.

I did not think as much of Crowley’s achievements as Arthur Symons had thought of Verlaine’s when, as a young man, he made, in the company of Havelock Ellis, the journey which brought him face to face with the French poet. But I am sure that I felt every bit as keen. Whether I believed in magic or not, or thought Crowley a great poet or just one of the also-rans, I was going to meet a man who had devoted his life to kicking against the pricks, and about whom floated a hundred legends. And although an old man is not necessarily a wise one, the paying of one’s respects to an old poet is homage to all the past.

In addition, I had a personal reason for wishing to meet Crowley: I had been warned with a shudder by a lady in whose house I had lived, when I mentioned that I wanted to meet Aleister Crowley, not to do anything of the kind, for he had put a spell on her husband and it had taken her ten years of prayer to exorcise it.

The moment arrived at last. As he was about to enter the room, I drew back to take the full impact of him.

He was not much more than medium height, slightly bent, and shrunk into an old-style plus-four suit with silver buckles at the knee. In his eyes was a staring, puzzled, pained look. He had a little goatee beard and his hair, or what remained of it, was cut close. A large ring was on his finger and a brooch of the god Thoth on his tie.

‘Do what thou wilt, shall be the whole of the law,’ he said in a nasal and fussy tone of voice.

The ‘Wickedest Man in the World’, as Crowley had been called, did look a little wicked, but mostly rather exhausted—whether from wickedness, or from old age, I did not then know.

It was an awkward meeting in rather mediocre circumstances—the drawing-room of the average boarding-house is not, after all, either the most diabolic or the most romantic of surrounding.

I remember that when we began talking about astrology, a subject which Crowley said he hardly believed in. This opinion rather surprised me, in view of the fact that he had been casting horoscopes for himself and others all his life and could more easily tell you what degree and sign of the zodiac the sun was in, than whether the day was Tuesday.

But astrology is a good subject for strangers to get together over, and by the time we had dropped astrology and gone on to magic, we had begun to feel at home.

As lunchtime approached, he kindly ordered lunch for us and retired. He did not eat much now, apart from sweets and sugar (ten spoonfuls in a cup of tea) and drugs. He had a voracious appetite for heroin. Later I was to see him raise a skeleton arm and inject himself with this drug.

‘Do you mind?’

‘Not at all; can I help?’ I replied.

He explained that recently an army officer had shown such a distasteful face when he had prepared himself for the syringe, that he had gone next door to the bathroom. He added drily: ‘I left the bedroom door open, and from behind the bathroom door I bent down to the keyhole and began to squeal like a stuck pig. When I came out, I found my poor friend had almost fainted.’

Before we left, he gave us each a copy of his Book of the Law, which, he said, was dictated to him in Cairo in 1904 by a spirit called Aiwass. This work is the bible of a new religion for mankind, an orgiastic piece of writing containing two fundamental principles: that there is no law beyond do what thou wilt, and that every man and woman ‘is a star’ or, as Christians would say, has an immortal soul.

I saw Aleister Crowley on a few occasions after this. There was something about him which fascinated me. I cannot define what this ‘something’ was, but its explanation lies in the region where those symbols and archaic pictures cluster—that dark, almost impenetrable part of the mind called by psychologists the Unconscious. He was, after all, a magician, the modern Cagliostro; he had also been considered the devil himself or, at least, a man inspired by the forces of darkness. In his own eyes, he was just a god, one of the company of heaven.

At the end of 1947, Aleister Crowley, as Mr. Bax had predicted, died. The newspapers had found him good copy while he was alive, and they got out their files and rehashed his infamies for their obituaries of England’s famous ‘Black Magician’.

Amongst his papers I came across the strangest of documents: The Magical Record of the Beast 666. The Beast 666 was Crowley, a title he took when he attained the status of Magician. This Magical Record, or diary, is a day-to-day account, set down in the frankest way, of Crowley’s magical, or religious, activities, in which sex and drugs played a not inconsiderable part.

He was, indeed, the strangest of men. I realized how little I had known of him when I had sat beside him in his room in Hastings hung with his own uncanny paintings. Through these pages of his diary he returned in all his mature fascination and eccentric foolhardiness.

He had led a colourful life. In his youth he had published (at his own expense) volume after volume of poetry which, so far, the world has passed by. His mountaineering exploits have fared better, for he was considered a good rock climber. He was one of a party who made the first organized assault on the second highest mountain in the world, K-2, and, in 1905, he led the first attempt on Kanchanjanga, during which five men lost their lives. He wrote two (rather poor) novels. He drove a few women insane. But it is not for these activities that he asked the world to remember him. As a Cambridge undergraduate, he had decided that only magic could give him the fame that he thought he deserved, and by magic he meant the art which could teach him how to control the secret forces of nature. In those days the subject was handled by a little organization called the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, run by a tyrannical-minded gentleman of the name of Mathers [MacGregor Mathers]. The poet W. B. Yeats was a member of this organization. Crowley joined the Golden Dawn and speedily quarreled with its head. He then founded his own occult society which claimed to do better.

The stories about him are legion. Here is one of them:

The late Mr. Watkins, whose bookshop of occult and mystical works still flourishes off Charing-Cross Road, once invited Crowley to demonstrate his magic.

‘Close your eyes,’ said The Beast 666.

Mr. Watkins did so. When he opened them a moment later, all his books had vanished from the shelves.

Like the teachings of Karl Marx, Aleister Crowley’s creed is not found in one book, nor is it derived from one source. He took much from the ceremonial magic of the Golden Dawn; his sex-magic practices were derived from an Indian school of worshippers called the Tantrics. Upon this twin foundation he spread the personal revelation made to him by the spirit Aiwass. This is such a formidable array of technique and wisdom that one is not surprised that Crowley claimed so much for it. ‘Let the broken in spirit and the wayward genius come to me and I will set him on the right path,’ he cried. The stories of Crowley’s attempts, however, to help people find their true wills are disappointing: they frequently went mad or committed suicide instead, to the Master’s surprise and annoyance.

In saving the individual, society will, automatically, be saved too. Christianity is the name of society’s illness; it has held the world in bondage long enough. Fortunately a new aeon is looking round the corner, the ‘Aeon of the Crowned and Conquering Child of Horus’. Now this is an exceedingly abstruse part of Crowley’s teachings. I am by no means sure that I have grasped it, but as far as I can make out, after studying it for the absurdly brief period of only four years, I gather that the deity of this new religion is Crowley himself, and by Crowley himself I do not mean Aleister Crowley the man, but Crowley’s magical spirit in its eternal, transcendental and previously incarnated forms. Crowley was, in fact, only an old god (Pan) come down to earth, and he is due to appear again when the age of Crowlianity (or that of the worship of the Antichrist) commences.

He considered that his Abbey of Do What Thou Wilt [Abbey of Thelema] in Sicily was a model of the new society. What the world at large heard about it (in England through the pages of the Sunday Express and John Bull), it strongly condemned. In spite of Crowley’s belief in himself as one of the seven great men in the whole history of mankind, he was just dismissed by the incredulous public as an evil person—‘the demon Crowley’.

In 1929 he was expelled from France for a reason that has not been made clear. Because he was a spy for the Germans? A drug trafficker? Or just because he was someone the French were fed up with? He was, certainly, the head of an occult organization of which the German branch was the most active. In England and America Crowley had been denounced as a cannibal, but in Germany the Great Wild Beast 666, with his pagan gods and berserk law of doing one’s will, found his greatest response. Crowley’s law of Do What Thou Wilt seems to have been especially appreciated by the countrymen of Frederick the Great and Hitler. One of his German pupils, an old woman [Martha Küntzel] now dead, divided her worship between Crowley and Hitler, and believed that Hitler was her ‘magical son’ or pupil. She believed in the Book of the Law and agreed with Crowley’s opinion that the first nation which accepted this book would dominate the world. In 1925 she translated it and sent a copy to Hitler who was then trying to increase his powers by the occult arts. But I do not think that Hitler needed Crowley as a Master, or any lessons from his philosophy of doing one’s (true) will.

Crowley, like everyone else, was a product of his time in general, and of his upbringing in particular. His parents were religious fanatics, members of the Plymouth Brethren sect who believed in a literal interpretation of the Bible. They were ordinary people of the tradesman class who had made money and were able to send their son to a public school and to the university. Had they been more sensible parents, or had Aleister been less passionate and rebellious, they might have made a smug little Plymouth Brother out of him. The result, however, was the opposite of what they had imagined. His sympathies were entirely on the side of the enemies of heaven.

In rejecting his parents and their creed, he put in its place a myth about his noble birth (farcical to us, but only an exaggeration of the accepted Victorian snobbery), and, as he romped about the world, he called himself on different occasions and in different costumes, Count Svareff, Lord Boleskine, Sir Aleister Crowley and Prince Chioa Khan; and he turned the worship of Christ into the worship of Hidden Masters, ancient gods and demi-gods, and 328 demons of that system of magic which, according to those who are best able to judge, is supposed to work, ‘The Sacred Magic of AbraMelin the Mage.’

For a few hundred years Christian missionaries gad gone East; by the second half of the nineteenth century the Easy was paying us back. In 1875, the year Crowley was born, the Theosophical Society was founded in America by Helena Petrovna Blavatsky. She took butterflies out of the wintry air and expounded the principle of the single universal spirit. The sacred texts of the east were collected together and translated. A new technique for purity and power (yoga) was discovered by young men and women who lived in Bayswater bed-sitting rooms. Religions, including Christianity, were in the melting pot. Pan, slumbering since the Middle Ages, awoke and prowled around the capitals of Europe. One night he certainly met Aleister Crowley and converted him.

Since on one believes in magic today—it has, I think, been superseded by science—the magician Aleister Crowley presents an enigma: how was he able to exercise a quite unusual degree of fascination over people, some of whom, like the mathematician J.W.N. Sullivan and Professor Norman Mudd, were no mean intellects? The answer, I believe, is threefold: Crowley was a man who turned everything upside down. What others repressed, he wore as a mask and an outer garment. He was every man’s evil shadow—the demon Crowley with his black masses and orgies, drugs and Satanism. A quiet afternoon’s conversation with the Master Therion was a descent into the Unconscious.

Another reason is that Crowley, au fond, was not really, a terribly wicked man. He threw out Christ, but in Christ’s place he did not put some lukewarm agnosticism or blunt materialism. The Hidden Masters—he called them the Secret Chiefs—were set up instead; and he continued to seek wholeness through community and prayer. That is to say, he recognized a spiritual problem and spiritual means of solving it; but dispensing with the Christian conception of Grace, he believed man could overturn death by his own efforts and by means of a sexual-magical technique.

The third reason for Crowley’s appeal was simply in the fact that he stood for something which we have ceased to believe in. We can discard a disproved scientific theory, but an outworn cosmogony lingers on in our dreams. Crowley with his witches, vampires and familiar demons was accepted for the very reason that he was absurd—credo quia absurdum. He was the bogey-man who terrified the bourgeoisie—university undergraduates and old ladies who read about him in the Sunday papers. |