|

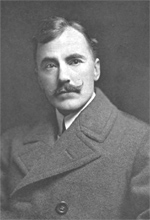

James Douglas

Born: 9 February 1867 in Belfast, Northern Ireland. Died: 1940.

James Douglas was a British critic, newspaper editor and author. He served as editor of the Sunday Express from 1920-27 and co-editor with John Gordon from 1928-1930. He was born in Belfast on 9 February 1867 into a God-fearing, relatively poor, and staunchly Orange family. Having left school at thirteen, he was for years an indentured apprentice in a linen factory until it was discovered that he was colour-blind and his indentures were cancelled. He then worked in a solicitor's office and took YMCA night classes, winning prizes for his Latin and Greek, before his mother 'scraped together enough money to pay for a coach' to enable him to matriculate at Queen's University, Belfast. Her dream was to make him a parson in the Irish Church. Instead, Douglas became private secretary to Sir Edward Harland, founder of the Harland and Wolff shipyard, who took the young man to London with him when he entered Parliament in 1889. Soon afterwards, Douglas married a woman from the same puritanical background as himself.

Douglas gradually made a name for himself in London's literary circles and became especially friendly with Swinburne, with whom he talked nearly every week. Given the sustained howl of moral outrage that had greeted the publication of Swinburne's Poems and Ballads, Douglas's admiration of the poet, like his ardent love of the theatre at this time, is hard to square with his subsequent apotheosis as the prude incarnate. The Douglas of this period come across as an altogether more fallible and appealing figure than the officious and overbearing smut-hound he would turn into. Although when Lord Beaverbrook was on the look-out for an editor for the Sunday News, it was less his emergent reputation as a prude that his established status as a cracker-barrel pundit for London Opinion and the Star that made him so attractive for the position.

Douglas announced his arrival as editor of the Sunday Express in an article of 14 March 1930 entitled 'Keen and Clean' in which he pledged that his newspaper would:

One of Douglas's broadsides was aimed at Aleister Crowley. 'Some time ago', Douglas wrote in November 1922:

Once again, however, Douglas had plumped for the wrong 'method' of dealing with a book he deemed objectionable. Before Douglas attacked it, The Diary of a Drug Fiend had been 'fairly widely and noncommittally reviewed' in the press, but, as was the case with The Flute of Sardonyx, Douglas's sensational account of it brought Crowley's book to far greater attention than a few literary reviewers could ever have done and it sold out its initial print-run.

Douglas's reviews of Crowley's book and other articles from the Sunday Express may be seen below: 19 November 1922 'A Book for Burning' 26 November 1922 'Black Record of Aleister Crowley' 25 February 1923 'New Sinister Relations of Aleister Crowley' |

circa 1909

1929

|