|

LITTLE POEMS

IN PROSE

at the sign of the black manikin

MADE AND PRINTED PARTLY IN GREAT BRITAIN, PARTLY IN FRANCE

Charles Baudelaire

LITTLE POEMS IN PROSE

TRANSLATED BY ALEISTER CROWLEY

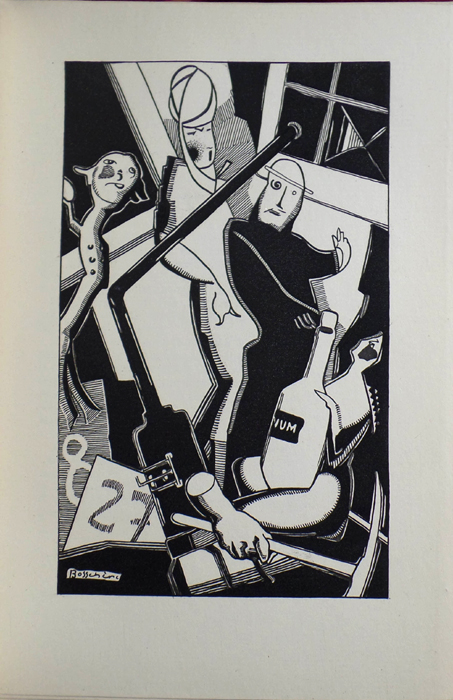

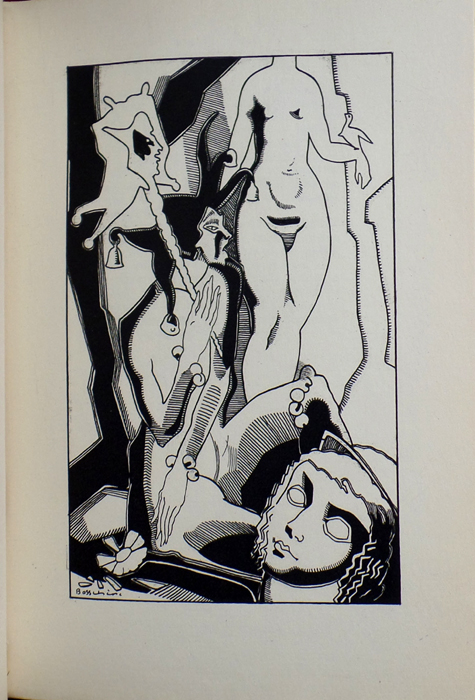

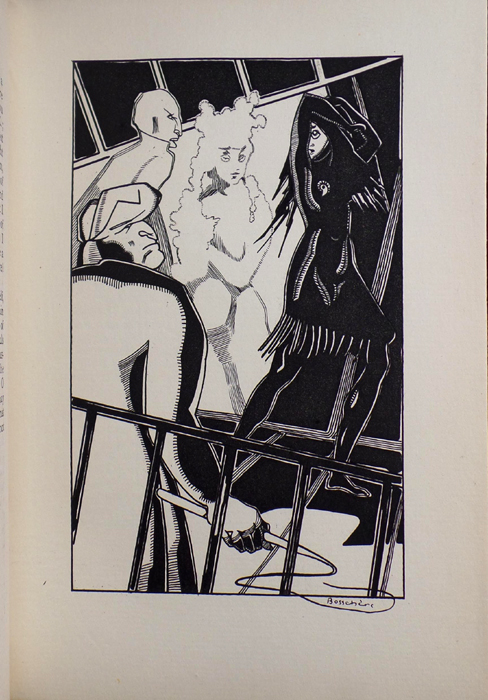

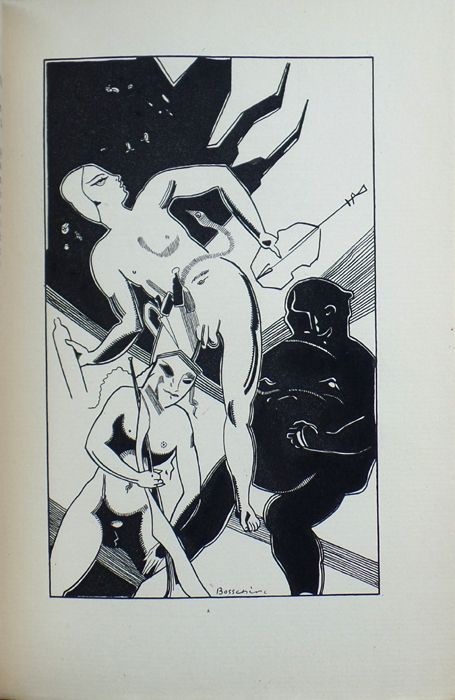

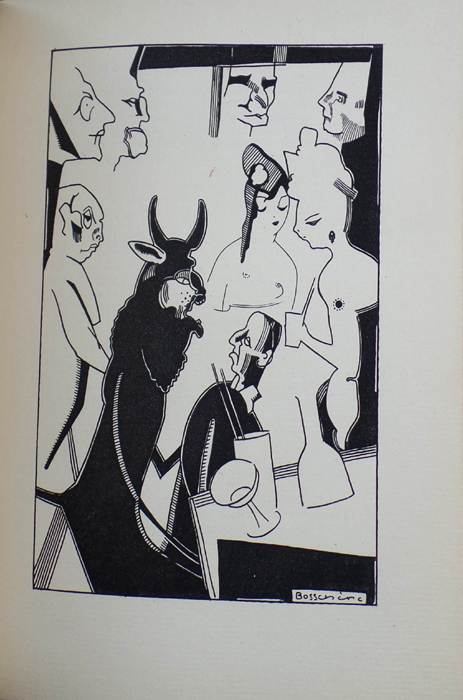

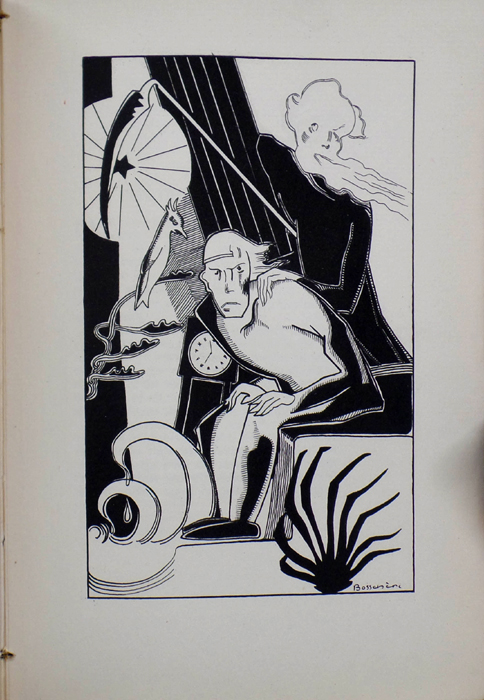

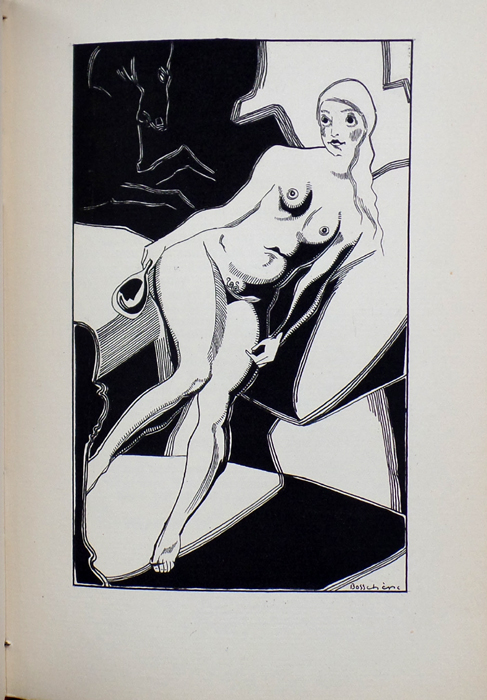

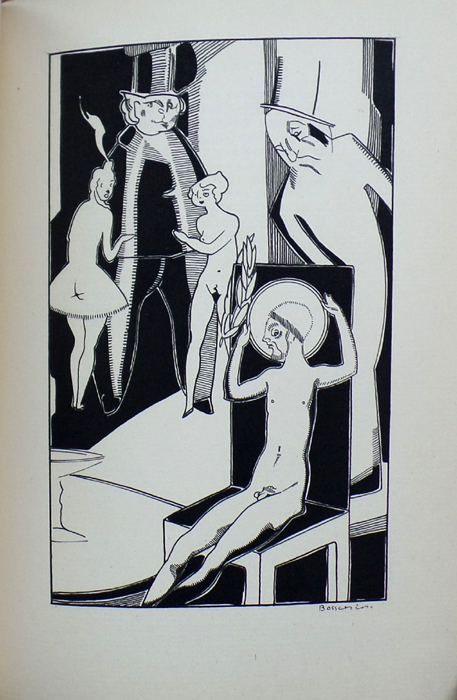

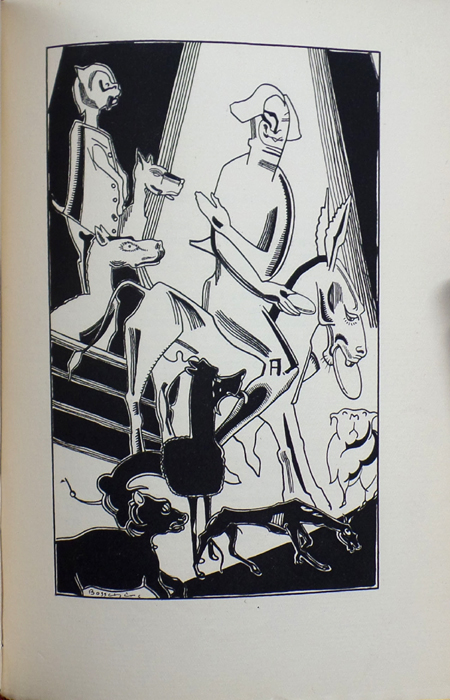

With several added versions of the Epilogue by various hands and twelve copper plate engravings from the original drawings by

JEAN de BOSSCHERE

EDWARD W. TITUS —— PARIS 4 RUE DELAMBRE

1928

Tous droits de reproduction, de traduction et d'adaption réservés pour tous pays y compris la Russie Copyright by Edward W. Titus

TRANSLATOR'S PREFACE

No bolder task can possibly be undertaken than the translation of prose so musical, so subtle, so profound as that of Charles Baudelaire. For this task I have but the one qualification of a love so overmastering, so absorbing, that in spite of myself it claims for me a brotherhood with him.

Charles Baudelaire is incomparably the most divine, the most spiritually-minded, of all French thinkers. His hunger for the Infinite was so acute and so persistent that nothing earthly could content him even for a moment. He even made the mistake—if it be, after all, a mistake!—of feeding on poison because he recognized the banality of food; of experimenting with death because he had tried life, and found it fail him.

The thought of Baudelaire has thus been universally recognized as highly unsuitable for the suburbs, as incompatible with any view of life which advocates spiritual complacency, mental and physical contentment. His writings are indeed the deadliest poison for the idle, the optimistic, the overfed: they must fill every really human spirit with that intense and insufferable yearning which drives it forth into the wilderness, whence it can only return charioted by the horses of Apollo and the lions of Demeter, or where it must for ever wander tortured and cast out, uttering ever the hyaena cry of madness, and making its rare meal upon the carrion of the damned.

This yearning has made all the saints and all the sinners; it severs man from his fellows, and sets his feet upon a lonely road, where God and Satan alone, no lesser souls, commune with it.

This yearning is the mother of all artists; in Baudelaire it reaches its highest and most conscious expression. It is for this reason that I tremble and weep, being as it were the bearer of his ashes into those smug lands where the noblest of al languages is prostituted to no other uses than those of gluttony, snobbery and greed.

The condition of England and America to-day makes it a profanation to translate Baudelaire; yet such is his virtue, and such the innate virtue of humanity, that if this volume only fall into the hands of the young, it may produce a crop of saints and artists even in those barren fields.

Aleister Crowley.

I AM DEEPLY INDEBTED TO FOR HER BRILLIANT AND INTOXICATING ASSISTANCE IN THE TASK OF REVISION.

A.C.

CONTENTS

I. The Stranger II. The Despair of the Old Woman III. The Artist's Confession IV. A Jester V. The Double Room VI. Everyone has his Chimera VII. The Madman and the Venus VIII. The Dog and the Flack IX. The Bad Glazier X. One O'clock in the Morning XI. The Wild Woman and the Spoilt Darling XII. Crowds XIII. Widows XIV. The Old Mountebank XV. The Cake XVI. The Clock XVII. A World in a Mane XVIII. Will You Come With Me XIX. The Poor Man's Toy XX. The Fairy Gifts XXI. The Temptations: or, Love Riches and Glory XXII. The Twilight of Even XXIII. Solitude XXIV. Plans XXV. Beautiful Dorothy XXVI. Poor Folk's Eyes XXVII. An Heroic Death XXVIII. Base Coinage XXIX. The Generous Gamester XXX. The Rope XXXI. The Joys of the Soul XXXII. The Thyrsus XXXIII. Intoxicate Yourself! XXXIV. Already! XXXV. Windows XXXVI. The Desire of Painting XXXVII. The Moon's Gifts XXXVIII. Whish is the True One? XXXIX. Thoroughbred XL. The Mirror XLI. The Harbour XLII. Portraits of Mistresses XLIII. The Polite Gunner XLIV. The Soup and Clouds XLV. The Cemetery and the Shooting Gallery XLVI. A Lost Halo XLVII. Miss Bistouri XLVIII. Anywhere, Anywhere Out of the World! XLIX. Death to the Poor! L. In Praise of Good Dogs Epilogue

Notes Versions of Epilogue by : Ralph Cheever Dunning Pierre Loving E. W. T.

THE STRANGER

WHOM do you love best, man of enigmas? Tell us:—Your father, your mother, your sister, or your brother? "I have neither father, nor mother, nor sister, nor brother." "Your friends?" "There you employ a word whose sense I have never understood." "Your country?" "I do not know its latitude." "Beauty?" "I would love it willingly, Goddess and Immortal." "Gold?" "I hate is as you hate God." "Ah, what then do you love, strange man?" "I love the clouds . . . . the clouds that float . . . down there . . . the marvellous clouds."

II

THE DESPAIR OF THE OLD WOMAN

THE little shrivelled-up old woman felt herself happy again in looking on the pretty child, to whom everyone was paying court, whom everyone was trying to please; a pretty creature, as fragile as the little old woman herself, and like her, too, without teeth or hair. And she approached it, wooing it with baby-talk and pleasing faces. But the frightened baby struggled in the arms of the hag, and filled the house with its screams. Then the good old woman withdrew herself again into her eternal solitude, and wept in a corner, saying to herself, "Ah, for us unfortunate old women the age is past when we can please even the innocent, and we frighten the little children that we wish to love."

III

THE ARTIST'S CONFESSION

HOW penetrating are the ends of autumn days! Ah, keen like pain! For there are certain delicious feelings whose vagueness does not prevent them from being intense, and no point is sharper than that of the Infinite.

How great is the delight of drowning one's look in the vastness of sky and sea; solitude, silence, incomparable chastity of the blue; one little sail shuddering on the horizon is like a reflection of my irremediable existence; the melodious monotony of the swell; all these things think by virtue of me, or I think by virtue of them (for in the vastness of the reverie the Ego is soon lost)—they think, I say, but musically and picturesquely, without quibbles, syllogisms, and deductions.

At the same time these thoughts, whether they arise from myself or dart forth from things external, soon become too intense. Energy in pleasure creates uneasiness and positive suffering. My nerves, too highly strung, no more give forth any but scolding and painful cries.

And now the depth of the sky affrights me; its limpidity exasperates me. The insensibility of the sea, the changelessness of the prospect, revolt me. Ah! must one eternally suffer, of fly eternally before the face of beauty? O! no, pitiless enchantress ever victorious rival, leave me alone' cease to tempt my passion and my pride! The study of the beautiful is a duel where the artist cries with fear even before he is conquered.

IV

A JESTER

THE New Year broke in a chaos of mud and snow, crossed by a thousand carriages, sparkling with joys and sweetmeats, swarming with greeds and with despairs; the official delirium of a great city in conspiracy to disturb the brain of even the strongest solitary.

In the midst of this topsy-turvyness and hubbub an ass was trotting smartly, tormented by a knave with a whip.

As the ass was about to turn the corner of a pavement, a fine gentleman gloved and groomed, in a glossy suit, uncomfortably fashionable, bowed ceremoniously before the humble animal, and said, taking off his hat, "A happy New Year to you," then went back to his comrades, whoever they were, with a fatuous air, as if to ask them to ass their approbation to his self-content.

The ass did not perceive this would-be wit, and continued to run zealously where his duty called him. As for me, I was seized suddenly with immeasurable rage against this magnificent imbecile, who appeared to me to concentrate in himself the entire spirit of France.

V

THE DOUBLE ROOM

A ROOM which resembles a reverie; a truly spiritual room, where the hushed atmosphere is faintly tinged with rose and blue.

The soul takes therein a bath of laziness, rendered aromatic by regret and by desire. It is something like twilight; somewhat blue, somewhat rosy. A dream of pleasure at the hour of the eclipse!

The articles of furniture have long, low, languid shapes; one would say that they dream; they seem endowed, as vegetables and minerals are, with a somnambulistic life. The coverings speak with the same silent language as flowers, skies, and sunsets.

On the walls no artistic abomination; as compared with pure dream, unanalysed impression, definite and positive art is a blasphemy. Here everything has the suffering clearness and the delicious obscurity of harmony.

An infinitesimal scent of the most exquisite kind, in which is mingled a very slight moisture, swims in this atmosphere, where the slumbering spirit is cradled by hot-house feelings.

Muslin weeps before the windows and the bed; it spreads itself in snowy waterfalls. Upon this bed is couched the Idol, the Queen of Dreams. But how is she here? Who has brought her here? What magic power has installed he on this throne of reverie and of pleasure? What does it matter?—There She is; I recognize Her.

Look! See those eyes whose flame shoots across the twilight; those subtle and terrible Mirrors-of-Venus that I recognize by their terrifying malice. They attract, they subjugate, they devour the glance of the rash man who contemplates them. I have studied them often, those black stars which compel curiosity and admiration.

To what benevolent demon do I owe it that I am thus surrounded with mystery, with silence, with peace and with perfume? Oh blessedness! what we ordinarily call Life, even in its happiest expansion, has nothing in common with this supreme life which I now hold, and which I taste minute by minute, second by second.

No, there are no more minutes, there are no more seconds. Time has disappeared; it is Eternity which reigns, an eternity of delight.

But now a terrible and heavy blow is smitten on the door, and, as in infernal dreams, it seems to me that I receive the blow of a mattock in the midriff.

And now a spectre has come in. It is a bailiff, who comes to torture me in the Name of the Law, an infamous harlot who comes crying pity, and to ass the frivolities of her life to the sorrows of mine, or the guttersnipe errand-boy of an editor who wants the continuation of my manuscript.

The heavenly room, the Idol, the Queen of Dreams, the Slyphide, as the great René calls her, all this magic has disappeared at the spectre's brutal knock.

Horror! I remember, I remember! This hovel, this dwelling-place of ennui eternal, is indeed my own. Here is the foolish, dusty, battered furniture, and here the fire-place without flame or ember, befouled with spittle; the sad windows where the rain has traced furrows in the dust; the blotted or unfinished manuscript, the almanack where the pencil has marked the disastrous days.

And this other-world perfume, in which, with a sensitiveness made perfect, I grew drunk—alas! is replaced by the smell of stale tobacco mingled with I know not what sickening damp; one breathes here now the rancid air of desolation.

In this world, so narrow, yet so filled with loathing, one single well-known object smiles on me,—the phial of laudanum; and old and terrible mistress; like all mistresses, alas! fertile in caresses and in treacheries.

Oh yes, Time has reappeared. Time lords it now, and with the ugly oldster has returned all his devilish rout of memories, regrets, spasms, fears, agonies, nightmares, rages, nerve-storms.

I swear to you that the seconds now tick off like a mighty and a solemn bell, and each one leaping from the clock cries: "I am Life, Life intolerable, Life implacable, Life!"

There is only one second in human life whose mission it is to announce good news—the good news which breathes into every heart an inexplicable fear.

Yea, Time reigns; he has resumed his brutal dictatorship, and he drives me on, as if I were an ox, with his double goad. On, then, thick-head!—Sweat, slave! live, damnèd wretch!

VI

EVERYONE HAS HIS CHIMERA

BENEATH the great gray sky, in a vast and dusty plain that hath no road nor grass, without one thistle, without one nettle, I met several men walking, bowed over.

Each of them bore upon his back an enormous chimera, as heavy as a sack of corn or coal, or the heavy marching of a Roman infantryman.

But the monstrous brute was not a dead weight. On the contrary, it wrapped round and oppressed the man with its powerful and elastic muscles. It clutched with its two great claws at the breast of its mount, and its fables head crowned the forehead of the man like one of those horrific helmets by which the warriors of old time hoped to add to the terror of the enemy.

I questioned one of these men, and asked him where they were going. He answered me that neither he nor the others knew anything of this, but that evidently they were going somewhere, since they were driven by an invincible need of going on.

A curious feature of the affair was that none of these travellers appeared to be irritated at the frightful beast hung at his neck, glued to his back. One would have said that he considered it as an integral portion of himself. All these weary, serious faces witnessed to no despair; under the splenetic cupola of heaven, their feet plunged in the dust of a ground as desolate as that heaven itself. They went on their way with the resigned look of those who are damned to hope eternally.

And the caravan passed beside me and hid itself in the atmosphere of the horizon, at that point where the rounded surface of the planet withdraws itself from the curiosity of man.

For some moments I obstinately strove to understand the mystery; but soon irresistible indifference settled upon me, and I was more heavily weighed down by it than they themselves were by their own crushing chimeras.

VII

THE MADMAN AND VENUS

WHAT an admirable day! The vast park swoons under the burning eye of the sun like youth under the dominion of love.

The universal ecstasy of things expresses itself by no noise; the very waters seem to sleep; how different from human festivals! Here it is an orgy of silence.

One might say that an ever-increasing light makes things glitter more and more: that the excited flowers burn with desire to rival the sky's blue by the vigour of their colour, and that the heat, making their perfumes visible, sends them up before the altar of the day-star like clouds.

Nevertheless, in all this enjoyment I beheld one suffering.

At the fool of a colossal Venus, one of those artificial madmen, one of those professional buffoons whose duty it is to make kings laugh when remorse or weariness sits heavy upon them, muffled in a startling and ridiculous costume, with the horns and bells of a fool's cap, hunched up against the pedestal, lofts tear-filled eyes towards the pedestal, lifts tear-filled eyes towards the immortal goddess.

And his eyes say: I am the least and the most solitary of men; deprived of love and friendship, and in that respect how far below the least of brutes! Yet I am made, I too, to understand and to feel beauty immortal. Ah, Goddess, have pity of my sadness, of my madness!

But the implacable Venus looks afar off upon I know not what, with marble eyes.

VIII

THE DOG AND THE FLASK

"HERE, pupsikins, good doggie, nice doggie! Come and smell this delicious scent; it is by the best perfumer in town." And the dog, wagging his tail, which is, I suppose, for these poor creatures the sign which corresponds to smiles and laughter, comes near and with great curiosity rests his nose upon the unstoppered flask; then, suddenly recoiling in fright, he barks at me reproachfully.

Ah, wretched dog, if I had offered you a parcel of ordure you would have sniffed it with delight and very likely eaten it up! Unworthy companion of this sad life of mine, how you resemble the public, to whom one must never present the delicate perfumes which only exasperate it, but carefully selected scraps of nastiness!

IX

THE BAD GLAZIER

THERE are natures which are purely contemplative and altogether unfitted for action, yet which, under a mysterious and unknown impulse, sometimes act with a rashness of which they would have believed themselves to be incapable.

One such, fearing to find some disappointing intelligence at the porter's lodge, hangs about for an hour without daring to go home; another keeps a letter for a fortnight without unsealing it, or only makes up his mind after six months to take some step which was necessary a year before: such feel themselves sometimes hurried brusquely into action by an irresistible force, like the arrow from a bow. The moralist and the doctor, who set up to know everything, cannot explain whence comes so suddenly so mad an energy to flood these lazy and self-indulgent souls, and how, incapable as they are of accomplishing the most simple and necessary things, they find, at a certain moment, an ecstatic courage to execute the most absurd and even the most dangerous acts.

One of my friends, the most inoffensive dreamer that ever lived, once set fire to a forest to see, he said, if it would catch fire as easily as people generally say, Ten times running the experiment failed, but at the eleventh it succeeded much too well.

Another will light a cigar close to a barrel of gunpowder in order to see, to know, to tempt Fate, to force himself to give proof of his energy; to ape the gamester, to know the pleasures of anxiety; and this incited by caprice, by idleness, by nothing at all.

This kind of energy springs from boredom and reverie, and those in whom it so obstinately appears are in general, as I have said, the most indolent and dreamy of all beings.

Another, so mightily timid that he lowers his eyes even before the glances of his fellows, so that he must pull together all his little will to enter a café or a box-office, where the clerks seemed to him clothed with the majesty of Minos, Aeacus, and Rhadamanthus, will suddenly throw himself on the neck of an old man who happens to be passing and will kiss him enthusiastically before the astonished crowd.

Why? Because . . . because this countenance was irresistibly sympathetic to him? Perhaps; but it was simpler to suppose that he himself did not know why.

I have been more than once a victim of these cries and impulses, which give ground for the belief that malicious demons may possibly be asleep within us and cause us to perform, unknown to ourselves, their maddest whims.

One morning I got up in a bad temper, sad, tired of idleness, and impelled, it seemed to me, to do something big, a brilliant action; and I opened the window. Alas!

(Observe, I beg you, that the spirit of mystification which, with some people, is not the result of a preconceived plan but of a chance inspiration, participates very much, though it were but through the intensity of its desire, in this humour which doctors call hysteric, and which those who have a little more sense than doctors call Satanic, which compels us unresisting towards a crowd of dangerous or inconvenient actions.)

The first person that I saw in the street was a glazier whose piercing and discordant cry came up to me through the heavy and contaminated atmosphere of Paris. It would be utterly impossible for me ever to tell you why I was suddenly seized with a hatred, as sudden as it was despotic, against the poor man.

“Hullo, hullo,” I called to him to come up. At the same time I reflected, not without some amusement, that my room being on the sixth story, and the staircase extremely narrow, that the man was bound to find it rather difficult to make the ascent, and to catch in many a place the corners of his merchandise.

At last he appeared. Having examined all his glasses with curiosity, I said to him: “What, you have no coloured glasses?—Rose glasses, red glasses, blue glasses, magic glasses, glasses of Paradise! You impudent fellow; you dare to walk about in the poor quarters of the town, and you have not even glasses which make life look beautiful!” And I pushed him vigorously towards the staircase, where he stumbled and swore.

I went to the balcony and seized a little flower-pot; and when the man reappeared in the doorway I let fall my engine of war on the back edge of his shoulder straps, and the shock overthrowing him, he broke beneath his back all his poor walking stock-in-trade, which uttered the crashing cry of a glass palace split by lightning.

And, drunk with my madness I cried to him furiously: “Let life look beautiful, let life look beautiful!”

These nerve-gambols are not without danger, and one may sometimes have to pay heavily for them; but what does the eternity of damnation matter to one who has found in a second the Infinity of enjoyment?

X

ONE O'CLOCK IN THE MORNING

AT last alone. One hears no more of anything but the wheels of some belated and exhausted cabs. For some hours we shall be lords of silence, if not rest. At last the tyranny of the human countenance disappears, and I shall not suffer except from myself.

At last! it is then allowed me to take mine ease in a bath of shadows. First let me double-lock the door. It seems to me that this turning of the key will intensify my solitude and strengthen the barricades that separate me from the world.

Horrible life; horrible town! Let us go over the day's work. I saw several men of letters, one of whom asked me if it was possible to go to Russia by land. He doubtless thought Russia was an island. I disputed enthusiastically with the editor of a review who replied to every objection: "This is an honest newspaper;"—implying that all other newspapers were edited by scoundrels. I saluted a score of people, of whom I do not know fifteen. I scattered handshakes in the same proportion, and that without taking the precaution of buying gloves. To kill time during a shower I ran up to the rooms of an acrobat who begged me to design for her a costume as Vénustre. I paid court to a theatre manager who said, on saying good-bye: "You would do well perhaps to address yourself to Z.; he is the dullest, the most foolish and the most celebrated of all my authors; with him you might perhaps arrive at some arrangement. See him, and then we shall see." I bragged (Why?) of several dirty actions that I have never done, and cowardly denied several other misdeeds that I joyfully performed; thus committing the fault of boasting and the crime of respecting man. I refused to a friend an easy kindness, and gave a written recommendation to a perfect ass. There! is that enough?

Discontented with everybody and with myself, I should like to rehabilitate myself and regain my pride a little in the silence and solitude of the night. Souls of those whom I have loved, souls of those whom I have sung, strengthen me, sustain me, drive far from me falsehood and the corrupting vapours of the world, and Thou, O Lord my God, grant me Thy favour that I may make some good verses to prove to myself that I am not the meanest of mankind, that I am not inferior to those whom I despise!

XI

THE WILD WOMAN AND THE SPOILT DARLING

"REALLY, my dear, you tire me without measure or pity! One would say, to hear you sigh, that you suffered more than sixty-year-old gleaners, or the old beggar women who pick up broken crusts at the doors of dirty inns.

"If at least your sighs expressed remorse, they would do you some honour; but they only interpret your satiety of well-being, and that you are overwhelmed with rest; and then, you go on for ever spreading yourself in vain words: "Love me well; I have so much need of it; console me here, caress me there." Come, I will try to cure you; we shall perhaps find the means for a brace of half-pence in the middle of a festival.

"Let us consider carefully, I beg you, this solid cage of iron. Within it, howling like a lost soul, shaking the bars like an orang-outang made furious by captivity, imitating—and how perfectly!—now the tiger's circular leaps, now the stupid waddlings of the polar bear, excites himself this hairy monster—whose shape imitates, vaguely enough, your own.

"This monster is one of those animals which one generally calls 'My angel'; that is to say, a woman. The other monster, he who, a stick in his hand, cries loud enough to break your head in, is a husband. He has put his lawful wife in irons like a wild animal, and he is showing her in the suburbs;—on fair days, needless to say, with a licence from the magistrate.

"Pay close attention. See with what voracity (perhaps genuine) she tears to pieces the living rabbits and the cackling fowls which her keeper throws her. 'Come,' says he; 'one must not eat all one's fortune in a single day'; and with this prudent speech he cruelly tears from her the prey whose torn guts remain for an instant clinging to the teeth of the savage brute. I mean of the woman.

"Come, a good whack to quiet her! for she darts eyes terrible with greed on the food that he has snatched away. Great God! the stick is not a fool's bauble; did you not hear the flesh smack, despite the hide? And now too, her eyes jump out of her head; she howls more naturally than before. In her rage she sparkles all over, as when one beats hot iron.

"Such are the domestic matters of these descendants of Adam and Eve; these works of Thine hands, O my God! This woman is incontestably unhappy, although after all perhaps the titillating pleasures of glory are not unknown to her. There are more irremediable misfortunes; there are misfortunes that have no compensation. But in the world into which she has been thrown she had never been able to believe that women could ever deserve another fate.

"Now, between ourselves, my affected darling; to see the hells with which the world is crowded, what do you wish me to think of your pretty hell? You who rest only upon materials as soft as your own skin; eat nothing but well-cooked food, carefully carved by a clever servant.

"And all these little sighs which swell your perfumed breast, what can they mean for me, great strong coquette that you are? And all these affectations that you have learned from books, and this indefatigable melancholy, fit to inspire who looks upon it with quite another sentiment than pity? In truth I sometimes feel that I should like to teach you what real unhappiness is like. To see you thus, my beautiful invalid, your feet in the mire and your eyes turned dimly towards heaven, as if you wanted a king to play with, one might compare you with great accuracy to a young she-frog invoking the Ideal. If you despise King Log (as I am at present, you know well) beware of King Stork, who will crunch you and swallow you and kill at his pleasure!

"Poet as I am, I am not the dupe that you would like to think; and if you weary me too often with your affected complainings I will treat you like a wild woman of the woods or throw you out of the window like an empty bottle."

XII

CROWDS

IT is not given to everybody to bathe in the man-ocean; to enjoy the crow is an art; and he only can revel in their vitality at the expense of the human race in whom, while he lies in his cradle, a fairy has breathed the taste for travesty and masquerade, the hatred of home and the passion of travel.

Multitude—Solitude: these terms are equivalent, and are convertible by the active and fertile poet. He who does not understand how to people his solitude is equally ignorant of the art of being alone in a crowd.

The poet enjoys this incomparable privilege, that he can be at his pleasure himself or another. Like those wandering souls which seek for an embodiment, he enters where he will into the personality of each. For him alone all houses are to let: and if certain places seem to be closed to him it is because in his eyes they are not worth the trouble of being visited.

The solitary and pensive stroller draws a singular intoxication from this universal communion. He who easily weds himself to the crowd becomes acquainted with feverish enjoyments, of which the egotist, closed up like a strong-box, and the idle man, shut up in his shell like a mollusc, are eternally deprived. He adopts as his own all the professions, all the joys, and all the miseries which chance brings under his notice.

What men call love is very small, very restricted, very weak compared with this ineffable orgy, this holy prostitution of the soul, which gives itself altogether, all its poetry, all its good will, to every unexpected object, to the stranger who passes by.

It is sometimes well to teach the happy of this world, were it only to humiliate for a moment their foolish pride, that there are pleasures superior to theirs, pleasures more vast and more refined. Those who found colleges, who teach peoples, missionary priests exiled to the end of the earth, without doubt know something of these mysterious intoxications, and in the bosom of the vast family which their genius has made for themselves, they must sometimes laugh at those who compassionate them for their troubled fortune and for their life so chaste.

XIII

WIDOWS

VAUVENARGUES says that in public gardens there are alleys chiefly haunted by disappointed ambition, unfortunate inventors, abortive glories, broken hearts; by all those stormy and imprisoned souls in which still groan the last sighs of a tempest, and who recoil from the insolent gaze of the joyful and the idle: these shadowy retreats are the meeting-places of life's cripples.

It is above all to these places that the poet and the philosopher love to direct their eager guesses, which find there an assured pasture. For is there is a place which they disdain to visit, as I insinuated in the last story, it is above all the gaiety of the rich. That turbulence of emptiness has nothing to attract them. On the contrary, they feel themselves irresistibly drawn towards all that is weak, ruined, saddened, orphaned.

An experienced eye never deceives itself. In those set or languid features; in those eyes, either hollow or dull or shining with the dying lightings of their struggle; in those deep and many wrinkles, in those steps so slow or so dragging, he instantly deciphers innumerable legends of love deceived, of devotion misunderstood, of effort unrewarded, of cold and hunger humbly and silently endured.

Have you sometimes noticed widows upon these solitary benches? Widows who are poor; whether or no they be in mourning, it is easy to recognize them. Besides, there is always in the mourning of poor persons something lacking; an absence of harmony which makes it more heartbreaking. Poverty is obliged to haggle over its sorrow; Wealth weeps, regardless of expense.

Which is the sadder and more saddening widow? She who drags, holding his hand, a brat with whom she cannot share her reverie, or she who is quite alone? I do not know. . . . Once upon a time it happened to me that I followed during long hours a mournful old woman of this type; stiff, straight, under a little word-out shawl; she bore herself in all her being with stoical pride.

She was evidently condemned by absolute solitude to the habits of a celibate of long standing, and the masculine character of her manners added something mysteriously piquant to their austerity. I do not know in what miserable café and on what she dined; I followed her to the reading-room, and I watched her a long while, while she sought in the newspapers with quick glancing eyes, long since burnt out by tears, some news of powerful and personal interest.

At last, in the afternoon, under a charming autumn sky, one of those skies whence descend the armies of regret and of remembrance, she seated herself in a garden, aside, far from the crowd, to listen to one of those concerts whose regimental music the people of Paris so enjoy.

That was doubtless the little debauch of this innocent old woman, or shall I say of this purified old woman; the well-earned consolation of one of these heavy, friendless days, conversationless, joyless, bare of intimacy, these days which God let fall upon her since many days which God let fall upon her since many years may-be; three-hundred-and-sixty-five times in the year.

And yet another. I can never prevent myself from casting a glance, if not wholly sympathetic, at least curious, upon the crowd of outcasts who press upon an enclosure of a public concert. Across the night the orchestra throws festival chants, chants of triumph or of pleasure. The dresses fall glittering, glances are interchanged, the idle, fatigued because they have done nothing, waddle about pretending an indolent enjoyment of the music. Here is nothing but riches and happiness, nothing which does not breathe and inspire carelessness and the pleasure which life takes in allowing itself to live. Nay, nothing, unless it be the aspect of this mob which leans down there upon the outer barrier, catching, without payment, at the will of the wind, a shred of music, and gazing upon the sparkling throng within.

It is always interesting, this reflection of the rich man's joy in the depth of the poor man's eye; but this day, among this populace clad in blouses and calico, I saw a being whose nobility made a startling contrast with all the surrounding triviality.

It was a tall and majestic woman, so noble in her whole bearing that I do not remember to have ever seen her equal in the galleries of the aristocratic beauties of the past. A perfume of haughty virtue emanated from her whole person; her face, sad and thin, was perfectly in keeping with the full mourning in which she was dressed; she too, like the Plebs with which she had mingled, and which she did not see, she too gazed upon that glittering society with a thoughtful eye, and nodding gently her head, listened to the music.

Strange vision! Surely, said I to myself, this kind of poverty, if poverty there be, would not tolerate sordid economy; so noble a countenance is the guarantee of that. Why then does she remain willingly in a set of surroundings where she makes so startling a stain?

But my curiosity leading me to pass close to her, I thought that I could guess the reason. The tall widow held by the hand a child, clothed like herself in black. However moderate might be the charge of admission, it might perhaps be sufficient to pay for one of the necessities of that tiny being, or better still, a superfluity, perhaps a toy.

And no doubt she went home on foot ever meditating, ever dreaming, alone, always alone; for a child is troublesome, selfish, without sweetness or patience; and could not even, as a dog or a cat could, serve her as the confidant of her solitary sorrows.

XIV

THE OLD MOUNTEBANK

EVERYWHERE spread and moved and frolicked the holiday folk. It was one of those festivals on which, since long, mountebanks, trick performers, menagerie proprietors, and pedlars count to make up for the slack seasons of the year.

On such days it seems to me that the people forgets everything, both sorrow and toil; it becomes as children are; for the children it is a holiday, for the frown-ups it is an armistice concluded with the maleficent powers of life, a respite in the universal strife and struggle.

The man of the world himself, and the man engaged in mental labour, escape with difficulty from the influence of this popular jubilee. They absorb, without wishing it, their part of this happy-go-lucky atmosphere. For myself, like a true Parisian, I never miss passing in review all the booths which flaunt upon these solemn occasions.

They were in truth trying to outdo each other in hubbub; they chattered, bellowed, howled; it was a confluence of cries, opposing detonations, and sharp explosions; the 'Merry Devils' and the clowns twisted up the features of their weathered faces, hardened by the wind, the rain and the sun. They flung forth, with the confidence of trained comedians, witty sayings and jests as solidly and heavily comic as those of Molière. The strong men, proud of the size of their limbs, without either forehead or cranium, like orang-outangs, were strutting majestically beneath the tights which they have washed on the previous evening for the grand occasion. The dancing girls, beautiful as fairies or princesses, leaped and skipped under the lanterns whose flame crowds their petticoats with spangles. All was light, dust, cries, joy, tumult. One set was spending money, another making it; both equally happy. The children clung to their mothers' skirts, begging for sugar-sticks, or climbing on to their fathers' shoulders so as to get a better view of some juggler who seemed as dazzling as a god, and everywhere, dominating every other scent, was wafted an odour of frying, which was as it were the incense of this holy festival.

At the extreme end of the range of booths, as if, ashamed of himself, he had pronounced his own exile from all these splendours, I saw a poor mountebank, with bowed back, infirm, decrepit, a ruin of a man, leaning against one of the posts of his cabin: a cabin more wretched than that of the most brutish savage, and whose two candle-ends, guttering and smoking, yet lighted only too well his distress.

Everywhere joy, money-making, debauch; everywhere the certainty of to-morrow's bread; everywhere the frenzied explosion of vitality. Here only, absolute wretchedness; wretchedness dressed, to crown its horror, in comic rags, where necessity, far more than art, had introduced the contrast. He did not laugh, poor wretch! He neither leapt nor danced, nor gesticulated nor cried. He sang no song, either merry or sad; he made no supplication. He was dumb and motionless. He had given up the game; he had abdicated: his fate was come upon him.

But what a gaze (how profound, how unforgettable!) he cast upon the crowds and the lights, whose moving flood stopped a few paces from his repulsive wretchedness. I felt my throat caught by the terrible hand of hysteria, and it seemed to me that my gaze was dimmed by these rebellious tears—which would not fall.

What could I do? What good would it be to ask of that unfortunate one what curiosity what wonder he had to show within his stinking shadows, behind his torn curtain? In sooth I did not dare, and, though the reason for my timidity will make you laugh, I will avow it: I feared to humiliate him. At the end I brought my courage to the sticking point; I resolved, as I passed, to lay some money on one of the boards, hoping that he would divine my intention, when a great eddy of people, caused by I know not what disturbance, bore me far away from him.

And, on my homeward round, obsessed by this sight, I sought to analyse my sudden sadness; and I said to myself: I have just seen the image of the old man of letters who has survived the generation which he so brilliantly amused; of the old poet, without friends, without family, without children, degraded by his misery and by public ingratitude, into whose booth the forgetful world will no longer come.

XV

THE CAKE

I WAS travelling. The landscape which spread around me was irresistibly great and noble. Something of it doubtless passed at that moment within my soul. My thoughts flitted with a lightness like that of the atmosphere; vulgar passions, such as hate and profane love, seemed to me as far away as the clouds which defiled at the bottom of the abyss under my feet. My soul seemed to me as vast and as pure as the cupula of the sky which covered me. The memory of earthly things reached my heart weakened and diminished, like the sound of the bells of the unseen cattle which were feeding far, very far, on the slope of the opposite mountain. Upon the small unstirred lake, black by reason of its immense depth, there passed sometimes the shadow of a cloud, as if it were the reflection of the cloak of some giant of the air that flew across the heaven, and I remember that this solemn and rare feeling, caused by a motion vast in its utmost silence, filled me with a joy which was not untinged with fear. In short, thoughts of the beauty with which I was surrounded filling me as it did with enthusiasm, I felt myself at perfect peace with myself and with the Universe. I even believe that, in my perfect happiness and my total forgetfulness of all terrestrial evil, I had arrived at no longer thinking so ridiculous those newspapers which pretend that man is naturally good; when, immedicable matter renewing its importunities, I thought I would repair the ravages of fatigue and quench the appetite caused by so lengthy an ascent. I pulled out of my pocket a big chunk of bread, a leathern cup and a flask containing a certain elixir which chemists at that time were in the habit of selling to tourists, to be mingled, as opportunity arose with snow-water.

I was calmly cutting up my bread when a very slight noise made me raise my eyes. In front of me was a little ragged, tousled creature whose hollow, fierce, and as it were supplicating eyes, devoured the piece of bread, and I heard him sigh in a low, hoarse voice the word "Cake." I could not prevent myself laughing at the big name by which he dignified my plain bread, and I cut off a large slice for him and offered it to him. Slowly he came near, never letting his eyes leave the object which he coveted; then, snatching the piece with his hand, re recoiled actively, as if he had feared that my offer was not made in earnest, or that I might already be repenting of it.

But at the same instant he was overthrown by another little savage, risen from I know not where, and so exactly like the first that one might have taken him for his twin brother. They rolled together on the ground, disputing the precious prey, neither wishing to give up half to his brother. The first, exasperated, seized the second by the hair, but the other caught his ear with his teeth and spat out a bleeding morsel of it, with a superb oath in his uncouth dialect. The lawful owner of the cake strove to dig his little claws into the eyes of the usurper; the other used all his force to strangle his adversary with one hand, while with the other he tried to slip the prize of the fight into his pocket. But, re-animated by despair, the bitten one got up again and sent his conqueror rolling to the ground by butting him in the stomach. But why should I describe the hideous struggle, which lasted indeed far longer than their puerile powers had led me to expect? The cake journeyed from hand to hand and changed from pocket to pocket at each instant, but alas! it changed also in size, and when at last, exhausted, panting, bleeding, they stopped for lack of strength to go on, there was not, to tell the truth, any longer the bone of contention. The piece of bread had disappeared, and was scattered in crumbs like the grains of sand with which it was mingled.

This sight hard darkened the landscape for me, and the calm joy, in which my soul danced before it saw these miniatures of men, had vanished utterly. On that account I remained sad for a long while, saying to myself over and over again, "There is then a sublime country where bread is called cake, and is so rare a delicacy that it may beget war between brothers."

XVI

THE CLOCK

THE Chinese can tell the time by looking in the eyes of a cat.

One day a missionary, while walking in the suburbs of Nankin, found that he had forgotten his watch, and asked a little boy what the time was. The gutter-snipe of the Flowery Kingdom hesitated at first, then, recollecting himself, he replied, "I will find out for you." A minute later he reappeared, holding in his arms a fine big cat, and looking, as the saying is, in the white of its eyes, he unhesitatingly affirmed, "It is just a little before noon." This turned out to be the case.

As to me, if I bend over towards my beautiful Féline, so well named, who is at once the glory of her sex, the pride of my heart, and the incense of my spirit, whether it be night, or whether it be day, in broad daylight or thick darkness, in the abyss of her adorable eyes I always read the hour most clearly. This hour is always the same; vast, solemn, wide as space, without division into minutes or seconds; a motionless hour which is not marked on clocks, and yet is light as a sigh, swift as a glance. And if some importunate person where to come and disturb me while my gaze rests on this delicious dial, if some false and intolerant spirit, some demon of unlucky accident, were to come and say to me, "What are you looking at with such intensity? What do you seek in the eyes of this being? Do you see there the time? Ah, spend-thrift and do-nothing mortal!" I should reply unhesitatingly "yes, I see the time; it is eternity."

Now, Madam, is not that a really meritorious madrigal, and as pompous as yourself? In good sooth, I have taken so much pleasure in embroidering this pretentious piece of gallantry that I shall ask you for nothing in return.

XVII

A WORLD IN A MANE

LET me breathe long, long, the scent of thine hair; let me plunge my whole face into it as a thirsty man does in the water of a spring; let me stir thy tresses with thy hand like a perfumed kerchief to wave memories in the air!

If thou couldst know all that I see, all that I feel, all that I hear in thy hair! my soul goes journeying upon the wings of perfume like that of other men upon the wings of music.

Thy hair contains a world of dream, full of sails and masts; it holds great seas whose winds bear me to charming climates, where space is bluer and deeper, where the atmosphere is scented with fruit, with leaves, and with the skin of man.

In the ocean of thy man I see a harbour, bust as an ant-heap with melancholy songs, with vigorous men of every nation, and with ships of every style, whose fine and complicated architecture is silhouetted on a vast sky where stalks forth the eternal heat.

In the caresses of thy mane I find once more the langours of long hours passed on a divan, in the cabin of a tall ship; hours rocked by the imperceptible roll of the cradling harbour, among jars of flowers and cooling fountains.

In the blazing hearth of thy mane I breathe the scent of tobacco mixed with opium and sugar; in the night of thy mane I see glitter the infinity of tropical azure; upon the swan-soft banks of thy mane I intoxicate myself with the mingled odours of tar, of musk, and of the oil of coconut.

Let me bite long, long, thy black and heavy tresses; when I nibble thine elastic and rebellious hair it seems to me that I am eating memories.

XVIII

WILL YOU COME WITH ME?

THERE is a superb country; a country of Cockaigne, they say, which I dream of visiting with an old friend. Singular country, drowned in the fogs of our northern marches, which one may call the east of the west, the China of Europe, so much does warm and capricious fancy there take the bit in its teeth; so much has it been patiently and obstinately made illustrious by its wise and delicate flora.

A true country of Cockaigne, where all is beautiful, rich, quiet, straightforward. Where luxury takes pleasure in admiring itself in the mirror of good order; where life is easy and may be softly breathed; from which disorder, turbulence, and the unforeseen are shut out; where happiness is wedded to silence; where the food itself is at once poetical, rich, and exciting; where everything resembles you, dear angel.

You know the feverish malady which takes possession of us in times of wretchedness and cold; this homesickness for unknown countries; this pang of curiosity; it is a land which resembles you, where all is beautiful, rich, quiet, straightforward; where Fancy has built and adorned a Western China; where life may be softly breathed, where happiness is wedded to silence. It is there that we much go and live, it is there that we must go and die.

Yes, it is there that we must go and breathe, dream, make long the hours by reason of the infinity of sensations that they hold; a musician has written, "Will you dance with me?"; who will compose "Will you come with me?" That one may offer it to the beloved one, the soul's sister!

Yes, it is in this atmosphere that life is good—down there, where the slower hours contain more thoughts, where the clocks strike happiness with a deeper, a more meaning solemnity.

Upon glittering panels or upon gilded leather, darkly rich, live pictures; pictures blesséd, calm and deep as the souls of the artists which created them. The setting suns which so richly colour the dining-room or the 'drawing-room are sifted by fair stuffs or by high windows of stained glass; the furniture is vast, curious, bizarre, weaponed with locks and with secrets, like refined souls. Mirrors, metals, stuffs, jewelry, porcelain, play a silent and mysterious symphony for the eyes; and from all things, from every corner, from the cracks of drawers and from the folds of the curtains escapes a strange perfume—a "Come-back-to-me" from Sumatra—which is as it were the soul of the place.

A true country of Cockaigne, I tell you, where all is rich, clean, glittering like a beautiful conception, like magnificent plate, like splendid gold-work, like a mosaic of jewels. All the treasures of the world flow to it as in the house of a man who has well toiled and has deserved well of the whole world. Strange country, superior to all others, as Art is to Nature, where nature is re-formed by dream, where she is corrected, beautified, re-moulded.

Let them seek, let them still seek; let them ever push back the limits of their happiness, these alchemists of gardening; let them propose their prizes of sixty and one hundred thousand florins for whoever shall solve their ambitious problems; for me, I have found my black tulip and my blue dahlia.

Incomparable flower, re-discovered tulip, allegorical dahlia! It is there, is it not, in this lovely country, so calm and so dreamy, that we must grow, live, and flourish? Are not you framed in your analogy, and can you not admire yourself, to speak as the mystics do, in your own correspondence?

Dreams, always dreams! and the more ambitious and delicate is the soul, the more its dreams bear it away from possibility. Each man carries in himself his dose of natural opium, incessantly secreted and renewed. From birth to death, how many hours can we count that are filled by positive enjoyment, by successful and decisive action? Shall we ever live, shall we ever pass into this picture which my soul has painted, this picture which resembles you?

These treasures, this furniture, this luxury, this order, these perfumes, these miraculous flowers, they are you. Still you, these mighty rivers and these calm canals! These enormous ships that ride upon them, freighted with wealth, whence rise the monotonous songs of their handling; these are my thoughts that sleep or that roll upon your breast. You lead them softly towards that sea which is the Infinite; ever reflecting the depths of heaven in the limpidity of your fair soul; and when, tired by the ocean's swell and gorged with the treasures of the East, they return to their port of departure, these are still my thoughts enriched which return from the Infinite—towards you.

XIX

THE POOR MAN'S TOY

I SHOULD like to tell you of an innocent amusement. There are so few amusements that are not guilty ones!

When you go out in the morning with the intention of lounging in the streets, fill your pockets with halfpenny toys, such as the flat Punch, moved by a single thread; blacksmiths beating the anvil; the horseman and his steed whose tail is a whistle. And, as you walk by the inns below the trees, make presents of them to poor stranger children that you may meet. You will see their eyes grow great out of all knowledge. At first they will not dare to accept; it will seem too good to be true; then their hands will fasten lively on the present, and they will dash off as cats do, who go far away to eat the morsel you have given them, having learned to distrust man.

On a road, behind the pale of a large garden, at the end of which shone the whiteness of a pretty house bathing in the sun, was a beautiful, fresh-looking child, dressed in those country clothes which are so full of coquetry.

Luxury, freedom from care, and the custom of seeing wealth on all sides of them, make these children so pretty that one might think them made of another clay than the children of the middle or the poorer class.

Beside him lay in the grass a splendid toy, as fresh as its master; varnished, gilded, dressed in a purple robe and covered with plumes and beads; but the child was paying no attention to his chosen toy. And here is what he was looking at. On the other side of the pale, on the road, among the thistles and nettles, there was another child, dirty, puny, soot-begrimed; one of those outcast brats, whose beauty an unbiased eye would discover, if, as the connoisseur's eye divines an ideal painting under a coachmaker's varnish, he were to clean it from the repugnant rust of wretchedness.

Across these symbolic bars that keep apart these two worlds—the main road and the castle—the poor child showed the rich child his own toy, which the latter greedily examined as a rare and unknown object. Now the toy which the little gutter-snipe was teasing, worrying, and shaking in a wire box, was a living rat. His parents, doubtless for economy's sake, had chosen his toy from life itself, and the two children laughed together brotherly, and their teeth shone white, the one's no whiter than the other's.

XX

THE FAIRY GIFTS

THE Fairies had met in solemn session to distribute their gifts among all the new-born, children who had come into life in the last twenty-four hours.

All these old-fashioned and capricious sisters of Fate, all these bizarre mothers of joy and sorrow, were of many different kinds; some had a gloomy and sombre expression, others, a mischievous and clever one; some were young, who had always been young; others old, who had always been old.

Every father who believed in fairies had come, each one carrying his new-born child in his arms.

Their gifts, aptitudes, good luck, armouries of circumstance, were heaped up on one side of the Judge's box like prizes upon the platform at a school feast day; but this case was different in this particular respect, that the gifts were not the reward of any effort, but quite on the contrary a favour accorded to him who had not yet lived, a favour able to determine his fate and to become as well the source of his misfortune as of all his happiness.

The poor Fairies were extremely busy, for the crowd of clients was great, and their middle kingdom, placed as it was between man and God, is like us ruled by the terrible law of Time, and of its infinite posterity,—days, hours, minutes, and seconds.

In good sooth they were flurried as are ministers on a reception day, or the assistants in the Government pawn-shop when a national festival allows redemptions without interest. I even believe that from time to time they watched the hand of the clock with as much impatience as human judges who, in session since the morning, cannot prevent themselves from thinking of dinner, of their families, and of their comfortable slippers. If in supernatural justice there is a little hastiness and luck, let us not be surprised that it should sometimes be the same with human justice, for in that case we ourselves should be unjust judges.

Thus some blunders were committed on this day, which one might consider very strange if prudence rather than caprice were the distinctive and necessary character of the fairy folk.

Thus, the power of drawing fortune magnetically to himself was given to the sole heir of a very rich family, who, not being endowed with any sense of charity or with any greed for the visible goods of life was doomed to find himself one day terribly embarrassed by his millions.

So, too, a love of beauty and poetic power were given to the son of a dirty rascal, a quarryman by trade, who could not in any manner assist the development of the gifts, or supply the needs of his unlucky offspring.

I forgot to tell you that the distribution in these solemn cases is without appeal, and that no one may refuse a gift.

All the Fairies rose, thinking that their spell of hard labour was at an end, for there remained no more presents, no more bounties to throw among all this human trash, when a brave fellow, a poor little tradesman I think, rose, and catching her by her robe of many-coloured smoke the Fairy who was nearest to him, cried, "Ah, dear Lady, you are forgetting us, there is still my little child; I should be sorry to have come here for nothing."

The Fairy might have been embarrassed, for there remained no longer anything at all; however; she remembered in time a law very well known, though rarely applied in the supernatural world inhabited by these impalpable deities, friendly to man, and often constrained to yield to his passions, such as the Fairies, the Gnomes, the Salamanders, the Sylphides, the Sylphs, the Nixies, the Undines and their women-folk,—I mean the law which allows the Fairies in such a case as this, when all the gifts are gone, the power of giving yet one more additional and exceptional, provided always that she have sufficient imagination to create it on the spur of the moment.

The good Fairy then replied, with a self-possession worthy of her high rank, "I give your son—I give him—the gift of pleasing."

"But please how?—To please?—Why to please?" the little shop-keeper obstinately asked, for he was doubtless one of that very common class of reasoners who are incapable of rising to the height of the logic of the absurd.

"Because, because!" replied the incensed Fairy, turning her back upon him, and rejoining her companions, she said to them, "What do you think of this empty-headed little Frenchwoman who wishes to understand everything; and who, having obtained for his son the best of all gifts, still dares to ask questions and to discuss the inscrutable?"

XXI

THE TEMPTATIONS:

OR,

LOVE, RICHES AND GLORY

TWO superb Satans and a She-Devil not less remarkable than they, last night climbed the mysterious staircase by which Hell emerges to assault the weakness of a sleeping man, and secretly communicates with him. In their glory they came as it were erect upon a platform and stood in front of me. A sulphurous splendour emanated from these three mighty Beings, cutting them from the thick darkness of the night. So proud and so masterful was their manner that at first I took them to be indeed gods.

The face of the first Satan was epicene, and he had also in every line of his body the softness of old Bacchus. Lovely were his eyes, and languishing, of a shadowy and undecided colour, resembling violets still wetted with the heavy tears of the storm, and his half-opened lips seemed like warm caskets of perfume, whence he exhaled a subtle scent, and every time he signed, musk-scented butterflies gat light, on their winged way, from the ardour of his breath.

Around his purple tonic was twisted as a belt a gleaming serpent, who, with raised head, turned languorously toward him eyes that were like glowing coals. From this living girdle were suspended alternatively phials full of deadly liquids, shining knives, and surgical instruments. In his right hand he held another phial, filled with a luminous red liquid, and which bore these strange words: "Drink, this is my blood, the perfect cordial." In the left hand he bore a violin, which he used, no doubt, to sing his pleasures and his sorrows, and to spread the contagion of his folly on the nights of the Witches' Sabbath.

From his delicate ankles dragged some rings of a broken chain of gold and when the constraint which this occasioned him made him lower his eyes to the ground, he contemplated vaingloriously the nails of his feet, brilliant and polished like well-worked stones.

With his inconsolably sad eyes he looked upon me, with his eyes whence flowed an insidious intoxication. And he intones these words: "If thou wilt, if thou wilt, I will make thee the Lord of Souls, and thou shalt be the master of living matter, more so even than the sculptor can be of his clay, and thou shalt know the pleasure, ceaselessly re-born, of leaving thyself to forget thyself in another, and to draw other souls, until thou dost confound them with thine own."

And I answered him, "Thank you for nothing. What should I do with this parcel of beings, who doubtless are worth no more than my poor self? Though I have sometimes shame in remembering, I wish to forget nothing. And even if I did not know you, old monster, your mysterious cutlery, you ambiguous phials, the chains with which your feet are cumbered are symbols which explain clearly enough the inconveniences of your friendship. Keep your presents to yourself!"

The second Satan had not that air at the same time tragic and smiling, nor those insinuating manners, not that delicate and scented beauty. It was a hulk of a man, with coarse, eyeless face, whose heavy paunch hung over his thighs, and all whose skin was gilded and as if tattooed with the images of a crowd of little moving figures to represent the innumerable forms of universal wretchedness. There were little lank men who had hung themselves from a nail; there were little misshapen gnomes, exceeding thin, whose pleading eyes demanded alms even more than did their trembling hands, and then there were old mothers carrying abortions slung at their wasted breasts, and many another was there.

The great Satan knocked with his fist on his enormous belly, whence came a long, resounding clangour of metal, which ended in a vague groan as of many human voices, and he laughed, showing shamelessly his decayed teeth in an enormous and imbecile guffaw, just as do certain men in every country when they have dined too well.

And he said to me: "I can give thee that which obtains all that which is worth all, that which replaces all;" and he beat upon his monstrous belly, whose sonorous echo made the commentary on his coarse utterance.

I turned aside with disgust, and answered him: "In order to enjoy myself, I have no need of the wretchedness of anyone, and I refuse a wealth saddened like a soiled tapestry with all the misfortunes represented on your skin."

As to the great She-Devil, I should lie if I did not admit that at the first sight I found a bizarre charm in her. To define this charm, I know nothing better to compare it to than to that of very beautiful women who, though in their decadence, no longer grow older, and whose beauty has the penetrating magic of ruins. Her air was at once imperious and loose; and her eyes, although heavily ringed, were full of the force of fascination. What struck me most was the mystery of her voice, at whose sound I recalled both the most delicious contralto singers, and also a little of that hoarseness which characterizes the throats of very old drunkards.

"Wilt though know my power?" cried the false goddess with her charming and paradoxical voice; "Listen!" and she put to her mouth a gigantic trumpet covered with ribands like the reed-pipe, on which were written the titles of all the newspapers in the world, and through this trumpet she cried my name, which thus rolled across space with the noise of a hundred thousand thunders, and came back to me on the echo of the most distant of the planets.

"The Devil!" cried I, half conquered, "there is a precious thing!" But, in examining more closely the seductive Amazon, it seemed to me vaguely that I remembered having seen her drinking with some fools of my acquaintance, and the raucous sounds of the brass bore to my ears I know not what remembrance of a venal trumpet.

So I replied with all my scorn: "Be off with you; I am not the man to marry the mistress of certain persons whom I will not mention."

Certainly, of so courageous a self-denial I had every right to be proud; but unfortunately I awoke, and all my strength deserted me. "Indeed," said I to myself, "I must have been very soundly asleep to show such scruples. Ah, if they could return now that I am awake I should not play the prude."

And I called aloud upon them, beseeching them to pardon me; offering to give up my honour as often as must be to deserve their favour; but I had doubtless bitterly offended them, for they have never returned.

XXII

THE TWILIGHT OF EVEN

THE day falls; a great relief comes over the poor minds that are wearied with the day's toil, and their thoughts now take on the tender and uncertain colours of the twilight.

Nevertheless, from the level of the mountain to my balcony across the transparent clouds of even there comes a great howl, composed of many discordant cries, which space transforms into a mournful harmony like that of a rising tide or of a tempest which awakes.

Who are these unfortunate ones to whom evening brings no calm, and who, like the owls, take the coming of the night for the signal of their sabbath? This sinister ululation comes to us from the black asylum perched upon the mountain side, as I invoke the evening, smoking and contemplating the repose of the great valley dotted with houses whose every window says "Here now is peace; here is domestic joy." When the wind blows from above, there can I cradle my thought, that wonders at this imitation of Hell's harmony.

Twilight excites the mad. I remembered that I myself have had two friends that twilight positively afflicted; for the first, he lost understanding of all the relations of friendship and politeness and ill-treated the first-comer as a savage does. I have seen him throw an excellent fowl at the waiter's head because he thought he saw in it some insulting hieroglyph—how should I say what? The evening, forerunner of profoundest pleasures, spoilt the most toothsome things for him.

The second, a man of wounded ambition, became, as the day fell, more bitter, more gloomy, more teasing; indulgent and sociable enough all day, in the evening he was pitiless, and it was not only upon others, but upon himself also, that his twilight mania was wont to wreak its rage.

The first died insane, unable to recognize his wife and child; the second bears in himself the inquietude of everlasting little-ease, and though he were dowered with all the honours that republics can bestow, I think that the twilight would still inflame in him a burning desire of imaginary distinctions. The night which brings shadows, which brought shadows into their minds, makes light in mine. And though it is not so rare to see the same cause beget two contrary effects, I am always puzzled and alarmed by it.

Oh Night, Oh refreshing shadows! You are for me the signal of an internal festival, you are deliverance from anguish. In the solitude of plains, in the stony labyrinths of a great city, twinkling of stars or outbursting of lamps, you are the fire-work of the Goddess Liberty.

Twilight, how sweet thou art and tender! The rosy lights which linger still on the horizon like the death-spasm of Day trampled by the victorious car of Night; the torch-like flames which stain with their dull red the expiring glories of the setting sun; the heavy curtains which some invisible hand draws from the depths of the East:—these are but imitations of all the complex feelings which struggle within the heart of man in the solemn hours of his life.

Or lone like liken thee unto one of those strange dresses that dancing girls wear, where a dark transparent gauze lets glimmer the slain splendours of a shining skirt, as through a black present pierces the delicious past, and the vacillating stars of gold and silver with which it is sown represent those flames of fancy which do not truly kindle save under the deep mourning of Night.

XXIII

SOLITUDE

A PHILANTHROPIC journalist tells me that solitude is bad for man, and, to support this thesis, quotes, like all unbelievers, the sayings of the Fathers of the Church.

I know that the devil gladly haunts barren places, and that the spirit of murder and of lust inflames itself miraculously in solitudes; but it is just possible that this solitude is only dangerous for the idle and dispersed soul, which peoples it with its passions and chimeras.

It is certain that a wind-bag whose supreme pleasure consists in speaking from a platform or a rostrum would run serious trouble of becoming a furious madman on Robinson Crusoe's island. I do not demand from my journalist the heroic virtues of that adventure, but I do ask that he should not pass sentence upon those who love solitude and mystery. In our chattering race there are individuals who would accept with less repugnance the last penalty of the law if they were allowed to make a lengthy speech from the scaffold free from the fear that Santerre's drums might cut off their talk untimely.

I do not pity them, because I can see that their oratorial effusions procure for them pleasures equal to those which others draw from silence and contemplation; but I despise them.

I wish above all that my cursed journalist would allow me to amuse myself as I like. "You never feel then," says he to me, with a slightly apostolic snivel, "the need of sharing your enjoyments with others?" Look what a subtle form of envy is his; he knows that I disdain his pleasures, and he wishes to sneak into mine, the ugly spoilsport!

"This great misfortune of not being able to be alone," says somewhere La Bruyère, "as if to shame those who run to forget themselves in the crowd, fearing doubtless that they will be unable to tolerate their own company."

"Nearly all our misfortunes come to us from our not having the sense to remain in our chamber," says another wise man, Pascal, I think; thus summoning back into the cell of meditation all these wrong-headed persons who seek happiness in movement and in a prostitution which, if I were willing to speak the beautiful language of my epoch, I might call fraternitatal.

XXIV

PLANS

HE used to say to himself as he walked in a vast and lonely park, "How beautiful she would be in a Court dress, complicated and luxurious in the lovely evening air, coming down the marble steps of a palace opposite the broad lawns and the fountains; for she has naturally the air of a princess."

Passing by a little later in a city street, he stopped in front of a print-seller's shop, and finding a print representing a tropical landscape, he said to himself, "Ni, it is not in a palace that I should like to possess her dear existence; we should not be at home there; besides, those walls are so cumbered with gold that there would be no place to hang her picture. In those solemn galleries there would be no corner for intimacy; decidedly it is there, in that landscape, that one ought to dwell, to dream one's life-dream with due worship."

And, analysing the details of the engraving, he continued in himself, "At the edge of the sea a beautiful pleasure-house of wood, surrounded with all these strange and shining trees whose names I have forgotten; an intoxicating, indefinable perfume in the air; a powerful scent of rose and of musk in the house, and further, behind our little estate, tall masts swinging on the swell; around us, at the end of the room lighted by a rosy light filtered by blinds, decorated with fresh mats and heady flowers, with seats here and there in Portuguese rococo style of a heavy dark wood, where she would rest herself, so calm, so well at ease, smoking tobacco slightly flavoured with opium; beyond the compound, the noise of light-intoxicated birds, and the chattering of little negresses, and at night, to accompany my dreams, the plaintive song of musical trees, the melancholy filaos; yes, indeed, there is the surrounding which I looked for; what do I want with a palace?"

And further, going down a broad avenue, he saw a tidy little inn, where, from a window made cheerful by curtains of many-coloured calico, two laughing heads leaned out. At once he said to himself, "My thought must indeed be a vagabond to go so far to look for what is so near me. Pleasure and happiness live in the first inn one comes to; in the chance inn; is not chance the great mother of pleasures? A big fire, gaudy porcelain, a passable supper, rough wine, and a great bed with linen, a little coarse, but clean; what better is there in the world?"

But returning alone to his house at that hour when the advice of wisdom is no longer suffocated by the roar of the exterior world, he said to himself: "I have had to-day in dream three dwelling-places, which have given me one as much pleasure as the other; why inflict the trouble of travelling upon my body since my soul does it so easily, and why carry out plans, since planning is itself a sufficient pleasure?"

XXX

BEAUTIFUL DOROTHY

THE sun overwhelms the town with its direct and terrible light; the sand dazzles and the sea glitters; the tired world has given up its work and is taking its siesta; a siesta which is a kind of sweet-savoured death, where the sleeper, half awake, tastes the pleasures of his annihilation.

Dorothy, however, as strong and as bright as the sun, walks in the deserted street; at this hour she is the sole living being under the mighty vault of blue; she makes a startling black blot upon the light.

She moves forward, softly swaying her delicate torso on her broad hips; her robe of clinging silk, bright rose in colour, makes a lively contrast with the darkness of her skin, and moulds exactly her tall figure, her hollowed back and pointed breasts. Her red umbrella, filtering the light, throws on her dark face the blood-red tint of its reflections.

The weight of her forest of hair, almost blue in shade, draws back her delicate head and gives it an air at once triumphant and idle. Heavy earrings tinkle secretly at her dainty ears.

From time to time the sea-breeze lifts her floating skirt by the corner and shows her splendid shining leg, and her foot, like the feet of the marble goddesses that Europe puts into museums, makes a faithful print of its shape on the fine sand, for Dorothy is so prodigiously coquettish that the pleasure of being admired is more to her than the pride of the freed-woman; and although she is free, she walks bare-foot.

Thus she moves on, a harmony; happy in living, smiling an ivory smile as if she beheld afar off in space a mirror reflecting her movement and her beauty.

At the hour when the very dogs groan with pain under the biting sun, what powerful motive can have sent the idle Dorothy, beautiful and cold as bronze, upon her journeyings?

Why has she left her coquettishly arranged little house, whose flowers and mats make so cheaply so perfect a boudoir; where she takes so much pleasure in combing her hair, in smoking, in fanning herself or in looking at herself in the mirror of her great feathered fans, while the sea, beating on the shore a hundred yards away, makes its powerful and monotonous accompaniment to her vague reveries, and while the iron pot, where a dish of crabs with rice and saffron is cooking, sends its exciting perfume from the bottom of the courtyard.

Perhaps she has a tryst with some young officer, who, on distant shores, has heard his comrades speak of the famous Dorothy; no doubt the simple-minded girl will beg him to describe the Opera ball to her, and ask him if one may go there bare-foot, as one may on the Sunday dances, when the old Kaffir women themselves get drunk and furious with joy, And then again she will ask if the fair ladies of Paris are all more beautiful than she.

Dorothy is admired and petted by everyone, and she would be perfectly happy if she were not obliged to put aside copper after copper so as to buy the freedom of her little sister; who has all of eleven years and who is already a woman, and so beautiful. She will succeed, no doubt, this good Dorothy; the child's master is so miserly, too miserly to understand any other beauty than that of gold.

XXVI

POOR FOLKS' EYES

AH, you would like to know why I hate you to-day; it would doubtless be less easy for you to understand than for me to explain, for you are, I think, the finest example of feminine denseness that one might meet in a long day's march.

We had passed a long day together which had seemed short to me; we had promised ourselves that we should have all our thoughts in common, and that thenceforward our two souls should be no more than one. A dream which has nothing original about it, after all, unless it be that, imagines by all men, it has been realized by none.

In the evening you were a little tired, and wanted to sit down in front of a new café at the corner of a new boulevard; still full of rubbish, and already proudly displaying its unfinished splendours. The café sparkled; the gas itself flamed with all the enthusiasm of a first night, and lighted up with all its power the walls blinding with whiteness, the glittering surfaces of the mirrors, the gold of the rods and the cornices; the plump-cheeked pages dragged along by leashed dogs, the ladies laughing at the falcon perched upon their wrists, nymphs and goddesses carrying fruits, pastry and game on their heads, Hebes and Ganymedes offering with outstretched arms a little vase of soothing drinks, or the two-coloured pyramid of mixed ices, all history and all mythology dragged into the service of gluttony.

Directly before us on the pavement stood fixed a fine fellow of forty years old, with tired face and beard gone grey, holding by one hand a little boy, and carrying upon the other arm a little creature too weak to walk. He did a servant's office and took his children to taste the evening air. All were in rags. These three faces were strangely serious, and these six eyes looked fixedly upon the new café with equal admiration, but coloured differently by age.

The eyes of the father said: "How beautiful it is, how beautiful it is; one would say that all the gold of the poor world has come to plaster itself upon these walls." The eyes of the little boy: "How beautiful it is, how beautiful it is; but it is a house where people like us cannot enter." As to the eyes of the smallest, they were too fascinated to express anything less than a deep, dull joy.