|

THE EXPEDITION TO CHOGO-RI Leaves From the Notebook of Aleister Crowley

Published in the U.K. Vanity Fair London, England 8 July 1908 (pages 51-52)

The expedition roughly described in the following pages was intended, first, to capture for amateur climbers the last of the mountain records of the world; second, to vindicate humanity from the charge of being unable to climb above 23,000 feet. A failure it was; but interesting enough.

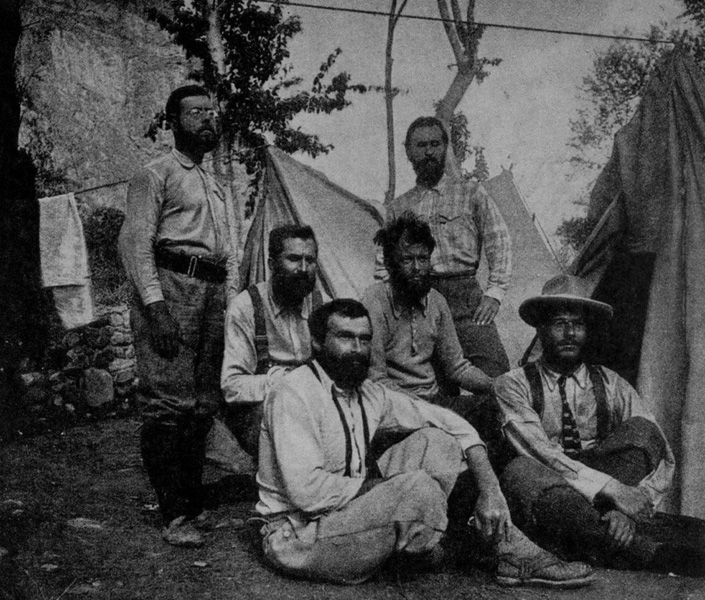

The Party. [From left to right, Victor Wessely, Oscar Eckenstein, Jules Jacot Guillarmod, Aleister Crowley, Heinrich Pfannl, and Guy Knowles.]

Besides Eckenstein [Oscar Eckenstein] and myself there were four new members: Knowles [Guy Knowles], an Englishman, who had rowed in the first boat for First Trinity, and was consequently, although a stranger to me, the best companion I could have wished. The others were foreigners; two of them were Austrians; Dr. Heinrich Pfannl, a judge; and Dr. Victor Wessely, a barrister; the last member was Dr J. Jacot-Guillaimod [Jules Jacot Guillarmod], a Swiss doctor. With regard to the Austrians, perhaps the less said the better. It will be sufficient if I mention that Pfannl, superb climber as he was, was totally incapable of realising the magnitude of the task we had set out to perform. He kept himself in the pink of athletic condition from the very start! On the 30th March I entered a prophecy in my pocket-book that if he collapsed it would be complete. However he continued to train. After a 15-mile march he would have a little tiffin, and then go off in the afternoon up the mountain side to keep himself in condition! On the 14th July he got ill; on the 15th he was worse; on the 16th the doctor fetched him down; on the 19th he was delirious; found himself with the illusion of triple personality, one of himself being in the form of a mountain, and anxious to kill him. During the 19th and 20th he was under morphia, and on the 21st he was taken down on a sleigh. As to Wesseley——— But enough of the Austrians!

In the Swiss doctor, however, we found an excellent companion and a medical advisor of sound good sense. From a mountain point of view, he was sadly lacking in experience, but he was certainly worth his place in the party, and more, for his constant cheerfulness and the fun we could always have with him. He did not mind being laughed at at all. He was not only good for our own harmony, but kept the natives in a good temper, and prevented them from desponding quite as much, or more, than the rest of us could do. They even invented a proverb: "Jahan Doctor Sahib tahan tamasha." "Wherever the Doctor Sahib is, there is amusement." Of all his tireless kindness to me I cannot speak sufficiently highly. Owing to various circumstances, I was thrown a good deal into his company.

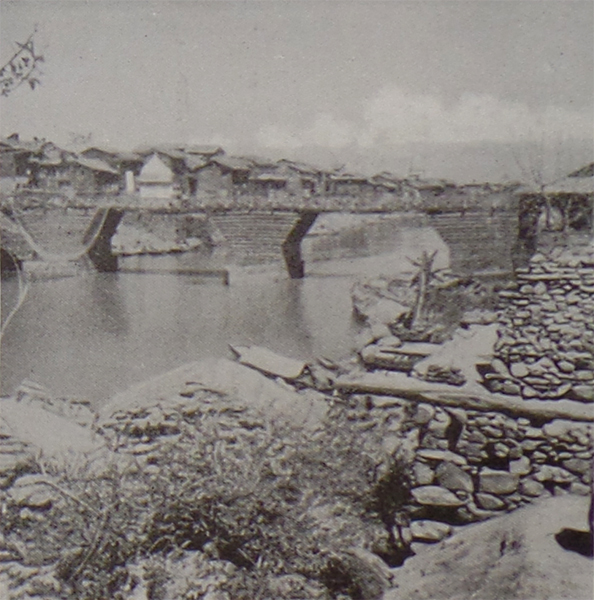

The Bridge at Simigar.

On the 24th March we got out at Rawal Pindi, and were held up there, owing to the non-arrival of our luggage. The Lime Tree Hotel was quite full, but they gave us tents outside, where we were very comfortable. The next morning I went shopping with Knowles, and we took the opportunity of discussing the finances of the expedition. As to this, I will only say that, had I known previously what the arrangements were, I should have entirely declined to have anything to do with the affair. One word of advice to anyone who intends going on an expedition with other Europeans. Either he has to pay everything and treat the others in every respect as servants, or the expenses to the last farthing ought to be shared equally by every member. If you pay more than your share, or less than your share, you are in an equivocal position; and if you pay for a man and yet treat him as an equal, the very fact that he is your guest prevents you speaking your mind. Nothing is more difficult after all than to lay down conditions which are not liable to misinterpretation. A good deal of the income of British lawyers depends on the difficulties which are met with in this respect by even the skilled legal draftsmen employed by the Houses of Parliament. But I suppose it is a ring!

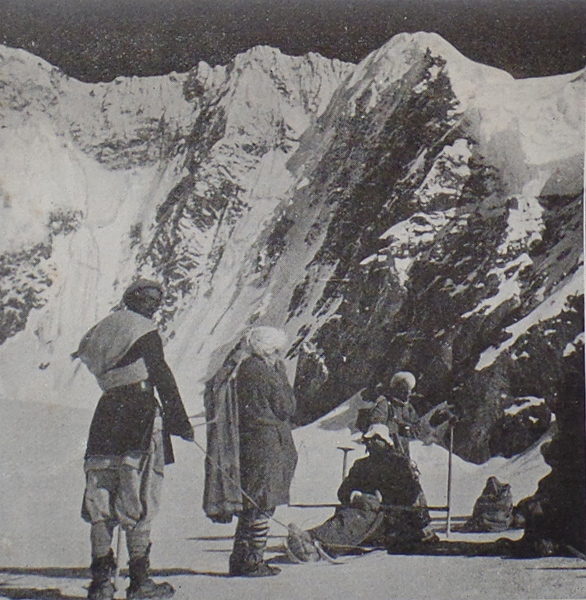

A Sleigh Ride.

The next few days at Rawal Pindi were spent in unpacking those cases which were too big to load on an ekka. An "ekka" is a vehicle drawn by one horse; in the back of the vehicle is room for a good deal of luggage, and more yet can be piled on top, leaving only a small place for the driver. The ekka, however, is of such a nature that, while it will accommodate seven of eight natives in apparent comfort, it does not show the same pleasing quality towards even one European.

Our Ekkas at Rawal Pindi.

The magnitude of our expedition may be gauged by the fact that our sea- borne and previously dispatched cases alone weighed over three tons. On the 29th March, after endless cursing, by dint of much physical force, we managed to get our baggage on to seventeen ekkas, and to start at 3 o'clock in the afternoon. We reached Tret the same night, a little before half-past ten, Knowles and I bringing up the rear to prevent any ekkas straggling; for if once an ekka is allowed out of sight it is likely to turn up three of four days later than you expect. No sooner had we reached the first night's stage—Tret—than an urgent summons forced Eckenstein to return to the plains, as it turned out, for over three weeks. We had some dinner, by no means before it was wanted, and went off to sleep in blissful ignorance of the catastrophe that was even then poised and about to strike us to the dust. |