|

THE EXPEDITION TO CHOGO-RI Part II Leaves From the Notebook of Aleister Crowley

Published in the U.K. Vanity Fair London, England 15 July 1908 (pages 71-72)

Knowles [Guy Knowles] and I did not go on with the main party, as we had to go off in a chikara (a sort of punt with pointed ends and an awning) to the Nassim Bagh, where we saw Capt. Le Mesurier and arranged one or two final details. The Nassim Bagh is a most charming spot, more like an English park than anything else. The sward is level and covered with grass, while everywhere are stately and vigorous trees. We hurried back to the town, where a dunga was waiting for us. A dunga is a very large flat-bottomed boat which can be and is used as a sort of inferior house-boat. It is divided into compartments by "chiks"—that is, curtains of bamboo or grass. In this boat we went off to Gandarbal, engaging coolies to tow us all night, so that we reached this village at daylight on the morning of the 29th.

I found Eckenstein [Oscar Eckenstein] under a tree holding durbar with Mata Kriba Ram, the Tehsildar of this district. When we had settled with him we strolled gently off to Kangan. I found myself somewhat thirsty and footsore, as I had taken no exercise for so long. The following day we went on to Gundisarsingh. We got off the coolies, 150 in number, as ponies were not to be had at this stage without any great difficulty.

I should explain here the system on which we worked. With such a large party of men it was impossible to keep the same men for more than two or three days; in any case it is impossible to know them all by sight, the more so that one is changing repeatedly. We therefore gave each man a ticket with his name and the number of his load, on the production of which and the load in question he was paid. Had we not done so, of course, every man in the neighbourhood would have hurried up like vultures scenting the carcass and claimed his pay as a coolie. Some of these naïve persons actually travelled four days in order to collect one day's pay which they had not earned!

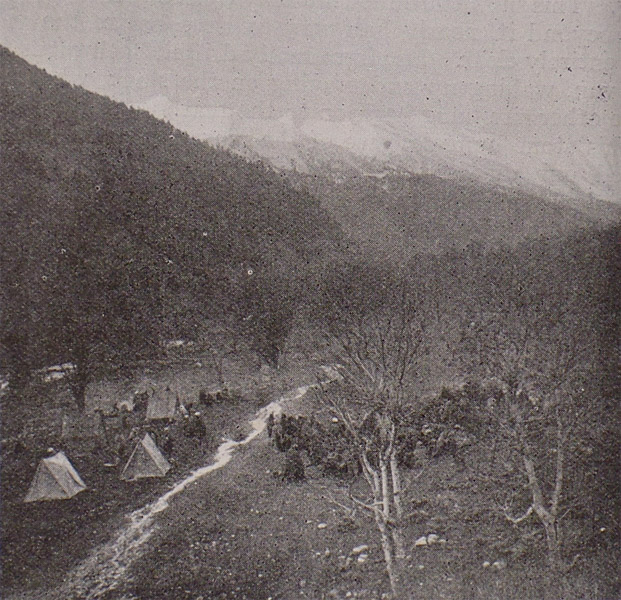

Gandarbal.

Though this stage is only 14 miles I arrived in a complete condition of collapse, a state which I always reach after doing a very little work. On May 1st we got on to Gagangir. The coolies tried to make us stop a good deal short of the proper stage. I was in the lead, however, and suspected that they were not telling the truth. I sent back a message to Eckenstein, and between us the conspiracy was overthrown. After getting to camp it began to rain hard and we had to put up the tents.

The next day we went on to Sonamarg through a most marvellous mountain gorge. The valley is exceedingly narrow and the path winds at the base of tremendous cliffs. Opposite, peaks, insignificant in themselves, tower to what seems a tremendous height, and their shapes and colouring are of very great beauty. Also on the opposite side of the river were the remains of vast snow avalanches, some of them broken off and kept under by the torrent. About half way the valley opens out, still affording fine views, however; Eckenstein and I were behind with the doctor [Jules Jacot Guillarmod], acting as rearguard. We passed a small village, crossed the stream below, and came across a lot of our coolies surrounding one of their number, who was lamenting his woes at the top of his voice. It seems that Abdulla Khan had hit him with a stick. He showed us a very insignificant bruise on his wrist and a big lump on his head; but the doctor was equal to the occasion. With regard to the arm, he touched him several times in places which would have hurt had the wound been genuine, and he remained calm; the doctor reversed the operation, when he screamed like a maniac. As to the lump on his head, it had been there 15 years! So we told him to shut up and go on.

Sunrise at Gagangir.

At Sonamarg they came to us in a body with a somewhat threatening aspect and refused to go if Abdulla Khan was allowed to hit them. This was the sort of occasion where hesitation would have been fatal, so I walked up to them and told them that I would discuss the question after tiffin, and in the meanwhile there were to go off and not worry us. Of course they went away. Eckenstein and I agreed to settle the question by taking charge of the rearguard ourselves, an arrangement which was accepted eagerly, as they had already learnt to trust us. The following day we sent Pfannl [Heinrich Pfannl] and Wesseley [Victor Wessely], whose exuberant energy had hitherto been so useless, to go up the Zoji La to prospect. The Zoji La was, of course, the one difficulty we were likely to meet. It is a pass about 11,000 feet high and snow-covered till late in May. We reached Baltal at the foot of the pass about noon. There was already snow in the valley at this place. There is no village, but a strong and sheltered house of stone, very convenient and indeed necessary for the dak-runners and travellers.

Pfannl and Wesseley returned in the afternoon. Their report consisted of three principal statements—(a) They could not see; (b) the pass was very steep at the Matayun side; (c) there was no snow on the Matayun side. Ignorant as I was of the topography of the place, such geographical knowledge as I had, and such geological data as I could get, forbade my believing the last two statements. To the first I gave my implicit adhesion.

Sonamarg.

A good deal of the afternoon was given over to a general inspection of the coolies by the doctor. Dark spectacles were given out to those whose eyes were weak or already inflamed. It was very amusing to watch the attempts at malingering on the part of perfectly sound men who wanted to get goggles, though, of course, we only lent them for the passage of the pass. Each coolie moreover who received a pair had a mark put against his name in Eckenstein's note-book. At four o'clock the next morning we had got everyone started. Pfannl and Wesseley had been sent ahead to cut steps if necessary. The doctor and Knowles formed the rearguard, while Eckenstein and I were to keep running up and down the line of coolies and see that there was no shirking. The duties of rearguard, however, became very heavy, and Eckenstein soon fell back to help them. About one o'clock they caught me up at a stone bungalow, which I imagined to be somewhere about the end of the stage. Yesterday's reconnaissance by the Austrians had been worse than useless. So far from the descent being steep it would have been difficult to locate the actual summit of the pass within two or three miles, and everything was deep in snow, as we found out before long. This snow continued not only right down to Matayun but beyond it, nearly half way to Dras, before the valley was entirely clear. I had gradually drifted backwards from the van, waking up and moving on the slack, who would have otherwise hung back on to the rear. After some rest at this stone bungalow, we of the rearguard, having transferred our duties, which had been extremely arduous, to Salama and Abdulla Bat, wandered slowly on. We kept together for a good deal of the way, though Knowles lost about two miles through trying to avoid getting wet. By this time the snow was abominably deep, and the walking utterly tedious. I sat down to wait for Knowles, and when he arrived after a long time, he was, if anything, in a better condition than I. We went on together some distance, but my knickerbockers had begun to chafe my legs and my marching became a very painful process. I arrived eventually at about five o'clock completely worn out. I must warn everyone that "Pattu" is a most unpleasant material. It is in no sense equal to the best English tweeds. I was unfortunately compelled to wear nothing else during the whole expedition, and the roughness and coarseness of the material entailed a good deal of suffering. Still worse is the stuff of which they make shirts. These are simply impossible. The hair shirt of the Asiatic is a bed of roses in comparison. Fortunately Knowles was able to get me have a shirt of very sound Welsh flannel, which lasted me for more than four months of continuous wear night and day, and was even then only worn thought at the elbows. On arrival at Matayun I simply rolled into my valise; drank half a bottle of champagne; ate a little food, and went to sleep like a log. I was very doubtful, indeed, as to whether I should be able to go on the morrow.

Approach to Zoji-La.

On the 5th we moved on to Dras, a very pleasant march, though rather long. We consoled ourselves, however, with the idea of a day's rest there, as we thought it very unlikely that coolies or ponies would be at our disposal. When we got in, however, we found 50 ponies waiting for us, and after a short consultation we decided to go on.

I gave orders for a saddle pony for myself, and Knowles followed my example, though Eckenstein did not altogether approve, for some reason that I have not been able to understand. If Knowles and I had known it was possible to ride nearly all the way to Skardu, we should have brought our riding-breeches; but Eckenstein, when he found it possible, seemed still unwilling, though in a very few days he came round to our views. The foreigners would not consent to ride; they were in that stage when hardship has its fascinations, and they thought there was something rather grand in making things as unpleasant for themselves as possible. I need not waste time in remarking on the fatuous imbecility of this idea.

(To be continued.) |