|

THE EXPEDITION TO CHOGO-RI Part III Leaves From the Notebook of Aleister Crowley

Published in the U.K. Vanity Fair London, England 22 July 1908 (pages 106-107)

As it was, I think we made a great mistake in not doing the whole of the journey, at least as far as Askoli, with large tents, beds, tables and chairs. Of course, our transport would have been largely increased. It was already beyond the ordinary capacity of the country, and this is no doubt the reason why Eckenstein [Oscar Eckenstein] did not make such arrangements. The truth was that a party of six was too large, especially as at least three of us had no capacity whatever for aiding the arrangements of valley travel. Knowles [Guy Knowles] and Eckenstein soon picked up enough Hindustani to make themselves understood, though I had to do the interpreting most of the time whenever it came to discussing any question which meant more than the giving of a simple order. Of course, Eckenstein remembered a little Hindustani from his previous journey, which soon came back to him; Knowles knew none, but he picked it up with wonderful cleverness and quickness. The foreigners seemed rather to avoid learning anything. The doctor [Jules Jacot Guillarmod] got over the difficulty by addressing the men volubly and at length in Swiss slang. Wesseley [Victor Wessely] used to talk German to them, and to lose his temper when they failed to understand him.

The next morning we found that ten of our ponies had been carried off by the shikaris of two English officers who were travelling on the same stages. The march to Karbu was very long and dull. I should certainly never have got there without the pony. When we arrived we found a polo match with musical accompaniments proceeding in our honour. Though very tired Eckenstein and myself sat down for a quarter of an hour, as politeness demanded, and having distributed backshish proceeded to the dak-bangla. On the 7th we again rode on to the appropriately-named Hardas. The road on this march became frightfully hilly. It must have been designed by a mad steeple-jack with delirium tremens.

Eckenstein had humorously observed at Matayun that "now it was all down hill to Skardu except local irregularities," but these local irregularities varied from 300 to 2,000 feet in height and followed one another rapidly with only a few yards of comparatively level ground between them. The whole of the valley on this side of the Zoji La presented a remarkable difference from that of the Kashmir valleys. There was literally no natural vegetation. The mountains were vast and shapeless, utterly lacking in colour or beauty of any sort.

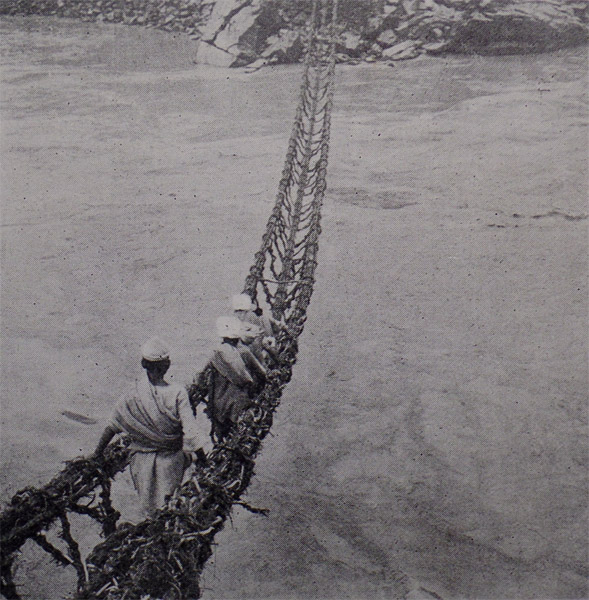

A Rope Bridge.

We were received at Hardas by the Rajah, with whom we had a lengthy conference about nothing. We eventually got rid of him by a present of some coloured pocket-handkerchiefs and a tip of five rupees. In this part of the country one did not need to be a republican to perceive the absurdity of kings.

On the 8th we proceeded to Olthingthang, a pretty long march. The road was a little more reasonable than the previous day, but a good deal of it was still very mad and bad. One stretch of several miles over a pari was exceptionally trying. It was broiling hot, and there was not a drop of water to be had anywhere; while the sun's heat came off the rock until one seemed as if in a furnace. But there was a delight to the eye marvellously marked on this day. In the midst of the naked hideousness of nature, wherever there had been a piece of ground sufficiently level, and a supply of water, cultivation had changed the ugliness of the Creator's design into an unconscious masterpiece of beauty. Imagine to yourself the tropical fervour of the heat, the dull drab of the rocks, the monotonous blue of the sky, and the sullen ugliness of the Indus with its dirty water running below your feet; then imagine yourself as if turning a corner and seeing in the midst of a new mass of rock a village. Ledge by ledge it would stretch down, clad in a brilliant and tender green, while cutting the horizontal lines of the irrigation channels, soared into the sky the magnificent masculine forms of poplars, and at their feet spread out the feminine and blossoming beauty of apricot trees. Village after village one passed, and was thrown every time into a fresh ecstasy of delight. There is a bitter disappointment, however, in store for the person who travels on this stage for the first time. The last pari is over; one sees a village in front nestling close to the Indus and watered by a large side stream which comes down in a succession of charming little cascades through a beautiful and verdant gorge -- but unfortunately it is not the stage! Just as one is certain that the weary march is over one finds that nothing is further from the truth. One has to ride up again more than a thousand feet from the valley before one reaches Olthingthang.

Our Reception by the Rajah of Tolti.

On the 9th we went on to Tarkutta. The "local irregularities" were again very severe. About half an hour from the start one joined the Indus Valley proper, though the river which we had been so long following was little less large than the main stream. The valley was also much grander though still very desolate. On the 10th we went on to Khurmang, another long march. I was again very ill, and found the air of the valley very filthy and stifling. The road was, however, a little more amenable to reason. At Khurmang is a wood fort very picturesquely perched on a steep rock. We were entertained on arrival by another beastly king. It was rather an amusing fact, though, that this king's complexion was a good deal lighter than any of us could boast of.

Ever since leaving Srinagar I had worn a pagri, which is perhaps the most comfortable form of headgear in existence, as it is good both against heat and cold. It is, of course, no good for rain, which it absorbs rapidly, becoming very heavy and clumsy; but in these rainless countries it is by far the best headgear that one could wear. For the first day or two it seems to afford little protection to the eyes, but one soon gets used to it.

The next day we went on to Tolti after defeating the plots of the Rajah's munshi. This ingenious person told us that it would be a very difficult matter to procure 150 coolies; but that if we advanced him five rupees he would send out messages to the outlying villages. Eckenstein, however, instead of doing this, asked the coolies who had come with us if they would go on another stage. They jumped at the chance, and made a regular stampede for the loads, going off that afternoon so as to avoid the heat of the following mid-day; but as soon as the munshi saw that they were well off he produced his 150 men (whom he had had in waiting all the time) and demanded to be paid on account of them. I cannot be sure whether Eckenstein did or did not give him a small installment of the kicking he deserved, as I was asleep in my tent during the whole of this commotion; but of course we reported his conduct to the authorities.

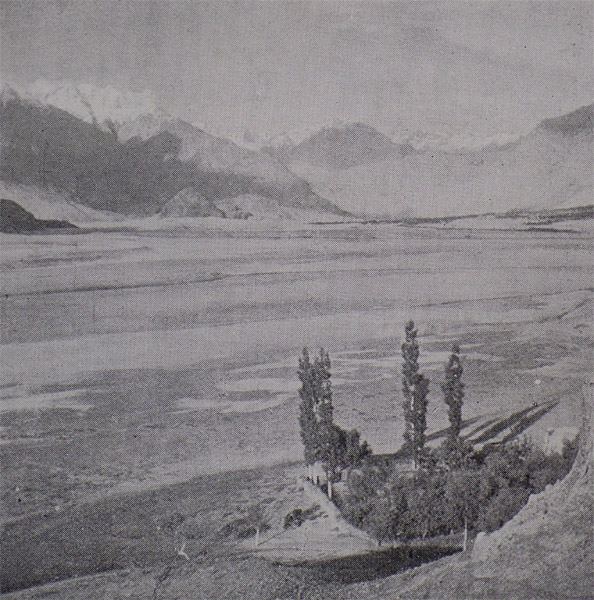

The Indus Valley.

The road to Tolti was less mad and bad than before, but still very bad and sad. We were met by yet another king, and the usual durbar took place. We went on to Parkuta. The road was now pretty good, and there was quite a length of the valley opening out. On the 13th we went on to Gol. The road was not capital for horses, except in the villages and over one or two pari. At Parkuta there must be five or six lineal miles of cultivated land, and we passed through many avenues of trees which afforded very welcome shade. On the 14th we finished the first stage of our journey, riding twenty-one miles into Skardu. There was a pretty good road nearly all the way and only two pari of any size to cross. I got in about noon, and we all settled down in a dak-bangla as we intended to rest at Skardu three or four days to get information about the possibility of crossing the Skoro La. About half an hour before nightfall a man was brought in who had had his leg cut open by a falling stone. The doctor immediately attended to it, but the darkness came on and the bulk of the operation was done by candle light. The doctor would not give an anaesthetic, and expected the boy to faint under the pain; but this did not by any means happen, though he was suffering as anyone must suffer under the circumstances. The leg was cut down to the bone from the knee to the ankle. He did not evince any signs of great pain, and only at one point did he open his lips and ask in the most casual way for some water.

The next morning we received a visit from the Rajah. This ruffian had been stripped of his power for his conspiracies, but he still enjoyed the title and a certain income. We got rid of him as soon as possible with one or two presents. Eckenstein and I then interviewed the Tehsildar who came to pay his respects, and to make arrangements for our further journey. Later a great wind sprang up and great storms of sand were to be seen in every part of the valley, some of them 3,000 feet in height. The valley was here very wide, it was rather like a great circular opening in the mountains than a valley, for the widening was not gradual but sudden, and soon closed in again.

Parkuta.

The next day two or three of us went off to fish, but caught nothing of any size. All the time, of course, we were overwhelmed with presents of one sort or another in the eatable line; while big pots of tea prepared in two different fashions were brought to us at nearly every stage. The first kind was made of Yarkand tea, sweetened and highly spiced; it was drinkable and even pleasant. The other was a mixture of tea, salt, and butter; and was an unspeakable abomination, though Eckenstein and Knowles pretended to like it. In the afternoon three brothers of the Rajah came and worried us. The next day nothing happened at all, and was consequently pleasant. On the 18th I went off with the Austrians to climb the fortress rock, which we ascended by the east ridge. It gave interesting and varied climbing; in the afternoon Eckenstein and I visited the Tehsildar and made the final arrangements. On the 19th we resumed our journey. About noon we reached Shigar, and made a delightful bivouac under a big tree. We were received by yet another Rajah! I had the bad luck to come in first; and was talking to him and the various lambadars for some time before the relief party turned up. In the Shigar Valley, not far from the village, are three fine carved Buddha-rupas in bas- relief on a big rock. After lunch I went off and shot some pigeons, and when I returned found that a guest was coming to dinner in the shape of the local missionary. We had a very pleasant dinner-party, and I entertained my companions by appearing first in the character of an earnest well-wisher to missionary work, with a gentle undercurrent which was quite beyond the comprehension of our friend; and subsequently in assuming the character of a prophet, demanding his allegiance. I proved to him my authenticity from the Scriptures, which, as it happened, I knew pretty well by heart; and put him down as one of those Scribes and Pharisees whose stiff-neckedness and generally viperine character prevented them from knowing a really good thing when they saw it! This man had been living in Shigar for seven years, and had not yet got a convert. Of course the Mohammedan regarded him as a very low type of idolater, and said so. He complained a good deal of his hard life; but as he was living in a most charming valley with a wife and all complete on a salary of which he could not have earned the fourth part in any honest employment, I do not quite see what he had got to complain of. Of course he laid stress on the absence of white men, but this was worse than no argument, as the possessor of such mediocre attainments, spiritual and intellectual, was not likely to receive anything but contempt in an educated community.

On the 20th we went on to Alchori, a short and pleasant march; I did a little pigeon shooting on the way. The Shigar Valley is broad and open, and the mountains on either side are delightful, though the bases are mostly uninteresting. The peaks in many cases have a fine pyramidal formation. The whole structure is thus rather of the type of the Wetterhorn seen from Grindelwald. One mountain, at the head of the valley, bears a striking resemblance to Mont Blanc, from Courmayeur.

(To be continued.) |