|

THE EXPEDITION TO CHOGO-RI Part VI Leaves From the Notebook of Aleister Crowley

Published in the U.K. Vanity Fair London, England 2 September 1908 (pages 310-311)

On August 1st the storm was more violent than ever. We heard from the Austrians, who were now at Bdokass, that cholera had broken out in the Bralduh Valley, and that it had consequently been closed by order of the Government. This was a very serious piece of news, as for all we knew it might imply difficulty (if not with regard to ourselves with regard to our baggage) in getting back to the Indus Valley.

After a long council on the subject it was unanimously decided that we had no option but to go down. Even had the weather cleared up at once the vast snow plateaux of Chogo Ri would have been impossible to traverse for at least a week. We had only a bare fortnight's provision remaining, and some of that was necessary for the return journey.

Chogo-Ri.

So the next fairly decent morning we finished the packing and struck camp. As, however, there were a good many more loads than we had coolies, we were obliged to resort to the sleigh, which was all right for a down-hill journey. We got off in the course of the morning and went down to Camp 9, stopping for half an hour or so at Camp Misery to extract sugar, milk and chocolate, together with a few of our permanent goods from the kiltas there. At Camp 9 we found our dakwale and got a very welcome mail.

The sleigh had broken down shortly below Camp Misery, as there was little or no snow on the ice here. The slope was much steeper than above, and the constant furious valley winds had blown all the new snow up to the big plateau outside Camp Despair. The sleigh had consequently gone to pieces, and the extra loads had been dumped. We sent men up to fetch them, and spent the day in idleness.

Striking Camp.

The following day we marched to Camp 7, Doksum: a very long march and much more tedious than the ascent had been, as there was now no snow whatever on the ice. The crevasses were large, and had occasionally to be circumvented; while the surface of the ice itself was honeycombed and consequently rather bad going. We had not expected this state of affairs, and got pretty hungry before we arrived.

We then sent men back for the extra loads, while two men went down to Bdokass for more coolies and flour. The last two days had been fine as far as we were concerned, but we could see the eternal storm still raging on the high peaks. This 7th of August was a very red-letter day. I washed, a thing I had not done for exactly nine weeks.

The following day I found myself very ill with a cold in my head from my imprudent conduct, and my digestive organs had again gone out of order. The Doctor [Jules Jacot Guillarmod] was better. I forgot to mention that he had been suffering severely from influenza for a week.

On August 10th we arrived at Camp 5. It was a long march, and I barely managed to arrive. We found the sandy glacier bed on which this camp is situated almost entirely covered with water. In the afternoon a violent rain storm arose.

The Retreat.

I had another very bad attack of sickness; but managed to start, the Doctor keeping with me till after mid-day, when I got a good deal better and was able to go down to Bdokass in comparative comfort. The route was entirely different to that I had taken in the ascent, as the old road from Camp 3 to Camp 4 was now a roaring torrent. In any case I should recommend this march, though a double one, to a future party. For quite a long way the glacier was reasonable level, and made walking quite a pleasure. This level part was almost bare ice, covered only with a thin layer of soree, which is of lovely rainbow hues. At Bdokass we found the Austrians waiting, and another mail; but there were no sheep, the Austrians having managed to eat eight in sixteen days, in addition to fowls, etc.! This is the more remarkable, as Pfannl [Heinrich Pfannl] had eaten but little owing to his illness.

We held a durbar in the rain to investigate the cause of the disappearance of our emergency rations; a large number of our self-cooking tins having disappeared from Camp Despair at a time when that camp was already short of food. A more mean and contemptible theft it was difficult to imagine. At night I had another bad attack of sickness. I am ashamed to say that it was largely my own fault. The taste of bread and fresh meat, revolting as it would have been to a civilised person, was so delicious after two months or more on tins that I over-ate myself. I had been very foolish staying out in the wet to attend the durbar, but the occasion was so serious that there was no alternative.

The Austrians left for good. They had some wild idea of going off to Darjeeling at that late date, and climbing Kinchinjanga; for which purpose they bought from the expedition a Munnery tent, their sleeping bags, valises, and other necessities. Of course such a scheme was totally absurd. The weather was still very wet, and the Doctor kept me in bed all day.

A Snake Charmer.

On August 14th marched to Liligo, which took us ten hours. Below Chorbutsé the marching was terribly bad. In coming up I had kept nearly all the way between the glacier and the hillside, which was good walking; but the stream had much increased, and quite half of the march lay over the glacier. For me indeed all of it did, as I left Chorbutsé later than the others, and a somewhat curious incident prevented me following the best route. The fording of the stream was only practicable in one place. As Eckenstein [Oscar Eckenstein] was crossing this a great deal of stuff broke away with him, and though Knowles [Guy Knowles] managed to get over immediately afterwards by Eckenstein's help, the way was subsequently impossible: so I had to wander along over the glacier itself for nearly two hours, cutting steps in a good many places for those of the coolies who like myself had been cut off. It snowed all the following night, but in the morning we were able to march to Paiyu. On the glacier I was prostrated with a sudden attack of fever, which kept me on my back for about three hours. I managed to crawl into camp in the afternoon. I had been altogether sixty- eight days on the glacier.

When we reached Bardomal I was obliged to stop there with the Doctor, while the others went on. Eckenstein, through some misunderstanding, left no food with us, and we had to dispatch a messenger. On this day the remainder of the party tried to cross the Puma Nala as we had done on the ascent. Eckenstein and four coolies got across roped with some difficulty; Knowles attempted to follow, but the people who were managing his rope let it trail in the water, with the result that he was swept away. Luckily he escaped with a couple of rather sharp knocks from stones, one on the thigh and the other on the neck, which latter very nearly rendered him unconscious. He very pluckily wished to try again; but the nerve of the others had been shaken by his misadventure, and they would not go; so he went round to the rope bridge, which, after all, was only a couple hours' détour, Conway's map being quite untrustworthy, and they reached Korophon that day.

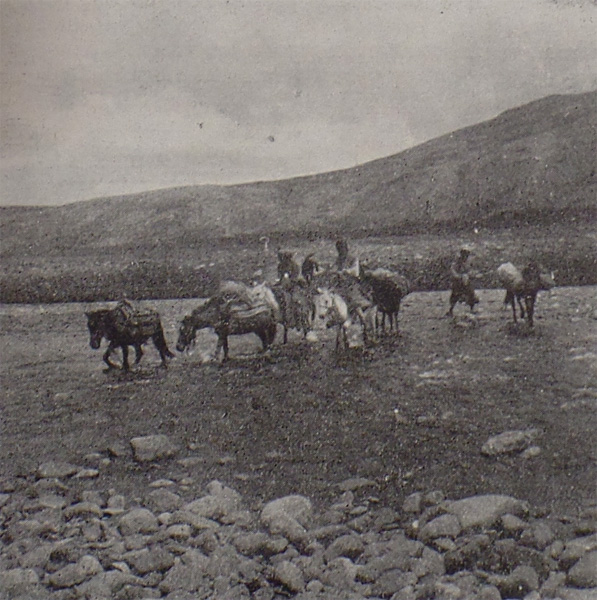

A Quaint Procession.

I felt a bit better and marched with my coolies to the hot spring, avoiding Askoli on account of the cholera. I may as well say here that this cholera business was a most mysterious affair. The officials at Skardu denied absolutely that there had been any epidemic at all or even any single case of cholera in the Valley during the whole summer, but the natives were unanimous that some sixty men had died in Askoli; and it is certainly unlikely that the lambadar to whom we owed money should not have turned up for payment if we was alive! A still more striking incident is that of the Chaprasi at Paiyu. This man was interviewed separately by Eckenstein and myself. To Eckenstein he told a long yarn about the cutting off of the Valley and the difficulty we might find in removing the property we had left at Askoli, while to me he said there was no difficulty. Further Eckenstein succeeded in bringing his Askoli coolies to Shigar, and was informed that the order permitting this had only just been issued. I, however, descended by the Valley route; and not only had no trouble whatever, but heard that a few days before a British officer who had been shikaring in one of the nulas had descended in front of me also without trouble. Knowles and Eckenstein in presence of the reputed epidemic completely lost their heads. Instead of taking the Doctor's advice to go and have a general clean up at the hot spring, they declined with horror "to remain in the affected district an hour longer than was necessary," but all the Askoli men were allowed by them to mix with our own coolies and the men of Sté Sté, the village opposite Askoli on the other bank of the Bralduh. The doctor believed in cholera as much, or as little, as I did, but, as a matter of form, he disinfected all the luggage we had left behind. Even this did not satisfy Eckenstein. He threw all our tea into the river, as well as a good many other things which we needed seriously afterwards. As soon as I arrived at the camp, which we pitched actually on the borders of the lake, I made a regular rush for the water, and had my first bath for eighty-five days!

(To be continued.) |