|

ON A BURMESE RIVER FROM THE NOTEBOOK OF ALEISTER CROWLEY

(PART IV)

Published in the U.K. Vanity Fair London, England 24 February 1909 (page 232)

I ought to have told you when talking of Ceylon, the delightful story of Allan's [Allan Bennett] adventure with a krait. Going out for a solitary walk one day with no better weapon than an umbrella, he met a krait sunning himself in the middle of the road. Most men would have either killed the krait with the umbrella or avoided its dangerous neighbourhood. Allan did neither; he went up to the deadly little reptile and loaded him with reproaches. He showed him how selfish it was to sit in the road where someone might pass, and accidentally tread on him. "For I am sure," said Allan, "that were anyone to interfere with you, your temper is not sufficiently under control to prevent you striking him. Let us see now!" he continued, and deliberately stirred the beast up with his umbrella. The krait raised itself and struck several times viciously, but fortunately at the umbrella only. Wounded to the heart by this display of passion and anger, and with tears running down his cheeks, at least metaphorically speaking, he exhorted the snake to avoid anger as it would the most deadly pestilence, explained the four noble truths, the three characteristics, the five percepts, the ten fetters of the soul; and expatiated on the doctrine of Karma and all the paraphernalia of Buddhism for at least ten minutes by the clock. When he found the snake was sufficiently impressed, he nodded pleasantly and went off with a "Good-day, brother krait!"

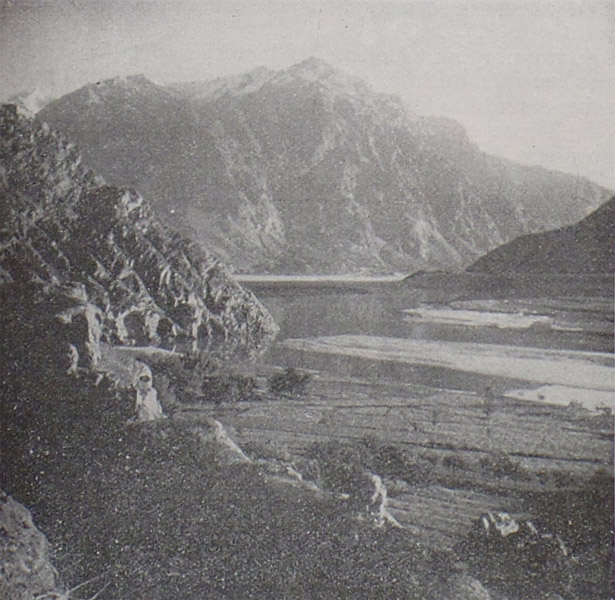

The Birthplace of Avalokiteshvara.

Some men would take this anecdote as illustrating fearlessness, but the true spring is to be found in compassion. Allan was perfectly serious when he preached to the snake, though he is possibly a better man of science than a good many of the stuck-up young idiots who nowadays lay claim to the title. I have here distinguished between fearlessness and compassion; but in their highest form, they are surely identical.

They managed to give me some sort of a shake-down, and I slept very pleasantly at the monastery. The next morning I went off to breakfast on board to say good-bye to the Captain, who had shewn me great kindness, and afterwards took my luggage and went to Dr Moung Tha Nu, the Resident Medical Officer, who welcomed me heartily, and offered me hospitality during my stay in Akyab.

He was Allan's chief Dayaka; and very kindly and wisely did he provide for him. I walked back with Allan to the Temple and commenced discussing all sorts of things, but continuous conversation was quite impossible, for people of all sorts trooped in incessantly to pay their respects to the European Bhikku. They prostrated themselves at his feet and clung to him with reverence and affection. They brought him all sorts of presents. He was more like Pasha Bailey Ben than any other character in history.

"They brought him onions strung on ropes And cold boiled beef and telescopes,"

and at any rate gifts equally varied and not much more useful. The Doctor looked in in the afternoon and took me back with him to dinner. Allan was inclined to suffer with his old asthma, as it is the Buddhist custom (non sine causa) to go out of doors at six every morning, and it is very cold till some time after dawn. I wish sanctity was not so incompatible with sanity and sanitation!

The next day after breakfast Allan came to the Doctor's house to avoid worshippers, but a few of them found him out after all, and produced buttered eggs, newspapers, marmalade, brazil nuts, bicarbonate of pot-ash, and works on Buddhism from their ample robes. We were able, however, to talk of Buddhism, and our plans for extending it to Europe, most of the day. The next four days were occupied in the same way.

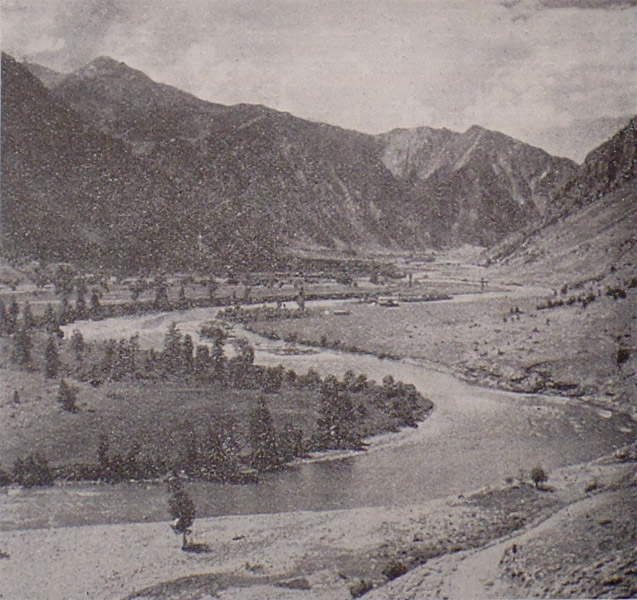

The Serpent Stream.

On Sunday I went aboard the S. S. Kapurthala to return to Calcutta. The next day we anchored outside Chittagong, a most uninteresting place. I was too lazy to land. Two days later I got back to Calcutta. Getting my mail, I busied myself in preparing for the great journey.

It was now definitely settled that our expedition should meet at Rawal Pindi. I only took one day off, when I went to Sodpur snipe-shooting with a friend of Thornton's, with whom I was now staying; Lambe [Harry Lambe] having gone off to Australia.

I left Calcutta late at night and arrived at Benares the next day. On Sunday I went to the Ganges to see the Ghats, and I also inspected the "Sex Temple," which after all compares unfavourable with the more finished productions of the late Mr. Leonard Smithers. The Temple of Kali, was, however, very interesting. Three months earlier I should certainly have sacrificed a goat (in default of a child), and I suppose by this time I may consider myself a pretty confirmed Buddhist, with merely a metaphysical hankering after the consoling delusions of Vedanta.

I however visited no less a person than Sri Swama Swayan Prakashan Raithila, a Maharaja who has become Saunyasi. After some conversation, he promised me that if I would return the next day he would show me a Yogi. He made a curious prophecy on the spiritual plane which was in a certain sense fulfilled without the torturing language which he used too much; but the prophecy which he made on the physical plane went somewhat astray.

(To Be Continued) |