|

|

(Joe and Pamela working as

the Scene rises. She is half dead with fatigue.

He is walking up and down, smoking. His march is

like an elephant on parade. It is 1:30 a.m.) |

|

Joe. |

(dictating) . . . . . a

clean-cut merchandising proposition on a basis

of genuine value. Point 14: the holders of the

preferred stock . . . . . |

|

Pamela. |

Preferred or deferred, Mr.

Davies? |

|

Joe. |

Preferred, of course. How

could deferred make sense? How often have I told

you to use your mind? |

|

Pamela. |

I'm sorry, Mr. Davies. It's

rather late tonight. |

|

Joe. |

And I'm paying for

overtime. Get on, please. The preferred of

preferred . . . |

|

Tim. |

(at window) Hullo, Joe! |

|

Joe. |

What's up? |

|

Tim. |

Oh I've been working at the

pit; accounts due tomorrow, I had to finish it

up. |

|

Joe. |

Sort of a dog's life, eh

Tim? |

|

Tim. |

Sure it is. If I could only

save a thousand dollars I could start something. |

|

Joe. |

Never in those trousers,

Tim! You aren't the sort. |

|

Tim. |

What's wrong? |

|

Joe. |

Nothing my boy, that's the

trouble. You've got all the virtues. See that?

(points to Pamela who has fallen asleep). That's

costing me one fifty per hour. Sleep begins now.

(snaps his watch). No work, no beer. |

|

Tim. |

Have you no heart, Joe? |

|

Joe. |

Haven't met the right kind

of girl. |

|

Tim. |

I didn't mean that, but now

you say it I think love will make another man of

you. |

|

Joe. |

(considering) Have a cigar,

Tim? |

|

Tim. |

You know I don't smoke or

drink? |

|

Joe. |

I know, you poor fish. I

forgot there were people like that. Girls now,

well, the girl for me . . . |

|

Tim. |

Why not Miss Gopher and her

five million bucks? |

|

Joe. |

Well said, my lad. I think

that's my ticket . . . Jove!—Tim, I wish I had a

million to grubstake me; I bet I could get her.

But a poor man—small chance in that racket! |

|

Tim. |

Yes, I can hardly imagine

"Sharper" Harper giving you his blessing. |

|

Joe. |

Damn the old fool! He's

pushed the market way up again for all his

stuff. I bet he cleared a million yesterday, the

bears were running to cover like damned rabbits. |

|

Tim. |

And where were you? |

|

Joe. |

So rotten short, you

couldn't see me with a microscope. It's all

Harper's personal magnetism; they daren't buck

him. But Longstaff and Workman are coming into

the ring tomorrow; it'll need all his guts to

beat 'em off. His stocks fell a quarter of a

point on that news, just before closing time. |

|

Tim. |

I understand they recovered

on the curb. |

|

Joe. |

Just a bit. But oh my God!

to be in that scrap tomorrow, with a million in

cash! |

|

Tim. |

Wishing won't bring it,

Joe. |

|

Joe. |

Willing, will, Tim. Here, I

must get this letter done. (shakes Pamela)

Sorry, but we must get point 14, and you can go

home, and bring me the transcript in the

morning. |

|

Pamela. |

Yes, Mr. Davies. |

|

Wilbur. |

(looking through the

window, his hand on his shoulder) Aha! So we

three meet again. There's something more than

natural in this if our philosophy could find it

out, which it can, for I'm just out for a

midnight stroll to see the moonrise, saw your

light, thought I would pass a festive minute.

Come, fill the bowl. |

|

Joe. |

The fact is, I'm fearfully

busy, Bill. |

|

Wilbur. |

So'm I, Joe. Busy like

hell! Can't sell a picture: want a dollar. |

|

Tim. |

Why that's funny; it

reminds me of that day we had the hallucination

about the fairy, and Joe and I . . . |

|

Joe. |

Yes, by gum! We did just

repeat our wishes . . . |

|

Wilbur. |

All hands present—except

the big fire—and my dollar. |

|

Joe. |

Tut! You chaps are wasting

my time. Sorry, but . . . |

|

|

(They turn away) |

|

Wilbur & Tim. |

Night-night, Joe! |

|

Joe. |

(firmly) Point fourteen! |

|

Wilbur. |

(returning) Curious

coincidence. There is a big fire tonight—looks

like Harper's place. Fine old house, and lovely

garden. Got leave to paint 'em once last summer,

and the old donkey never bought a canvas. Yes,

she's fairly ablaze. |

|

Joe. |

Oh, he's insured to his

last box of cigars. |

|

Tim. |

It's afire I tell you, the

house is afire! |

|

Joe. |

Well, we can't put it out,

can we? |

|

Tim. |

We can HELP! (he rushes

off). |

|

Wilbur. |

Nothing much lovelier than

a house on fire, or a ship! I should like to see

a ship, one with lots of powder aboard. Whoof! |

|

Joe. |

Lord! how you fellows waste

time. |

|

Wilbur. |

Well, may I earn that

dollar? Let me use your 'phone and ring up the

Post while you get on with Point

Fourteen. |

|

Joe. |

All right, use the hall

'phone. (Wilbur goes out). It's no use, Pamela,

my mind's upset. You can go home and I'll finish

in the morning. Nine sharp! (She says goodnight

and goes out). I got to get this thing clear in

my mind. Wonder if that's a trick of Sharpers. I

don't believe a cuss like that would ever have

an accident. Could it make any difference to the

market? (He is pacing the floor and smoking

savagely fast). No, I guess not. (He subsides

into beatific calm). |

|

Wilbur. |

(returns) A rotten day,

Bill. |

|

Wilbur. |

Not so, I've earned that

dollar. Hope for you by the same token. |

|

Joe. |

Can't figure it, Bill, no

how. Tim's got a better chance of that thousand. |

|

Wilbur. |

Oh cheer up! isn't that

blaze magnificent? Two scarlet steeple of flame,

and a purple wave of amethyst, like a cathedral

of our Lord the Devil. I wish I had my paints. |

|

Joe. |

I wish I was on the other

side of the market. It gives me a pain to think

how hopping mad the old boy will be; and he'll

take it out of us! |

|

|

(Neighbours bring in Mrs.

Harper, in hysterics, howling. They lay her on a

couch—one runs for water, another for salts,

etc.) |

|

Joe. |

(aside to Wilbur) Is this

place a hospital? |

|

|

(Presently Mrs. Harper

grows calmer, and faints away). |

|

Joe. |

Leave he lay! Don't fuss,

you fools. Never seen hysterics before? |

|

|

(Tim rushes in bearing

Blanche, in a dressing gown, on his shoulder). |

|

Blanche. |

Damn you, let me down. I

can walk. Where's my maid? |

|

Joe. |

Welcome to my poor house, I

fear there is no maid available, but anything I

can do . . . |

|

Blanche. |

Let me use a room to tidy

up, there's a good sport, then. Why, there's

aunt, fainting as usual. Say, Mr.—— I don't know

you're name—what is it? |

|

Joe. |

Joseph Davies, at your

service. Let me show you the way. (He goes out

with her and returns at once). |

|

Tim. |

It's horrible, horrible.

Poor old Harper—burned alive! |

|

Joe. |

(shouts) What! Say that

again! |

|

Tim. |

(stolidly) Poor old

Harper's burned alive! |

|

Joe. |

(shaking him violently) You

saw it—you saw it? |

|

Tim. |

I saw his face as I see

yours now, but his body was mostly cinders. |

|

|

(Joe turns away, masters

himself, lights a fresh cigar, walks up and

down). |

|

Tim. |

I must get back, there may

be more work to do. (rushes out). |

|

Joe. |

Wilbur—help me out! Get

these people out of the room; I've got to be

alone for five minutes. Come on, put 'em all in

my bedroom. |

|

|

(They clear the room. Joe

goes to the 'phone and sits thinking, takes off

receiver). |

|

Joe. |

Long distance, please Miss

. . . . . Is that long distance? . . . New York,

4319 Autumn . . . All right, be quick. (he sits

looking at his watch and saying "Damn" every ten

seconds or so.—The bell rings). That you, Blake?

Never mind what the hell; get your clothes on

and beat it to the Cable People. Don't trust the

'phone. Wire London in code to sell all Harper's

stuff short on our account—no, I'm not crazy, I

said SELL. Sell then cover; more wouldn't be

safe. Sell, sure. Never mind why; I don't trust

'phones; you get in on it for your last cent.

Matter with the street? Oh, get a move on; it's

nearly nine o'clock in London now and the whole

world will have my news in a couple of hours.

For Christ's sake, don't lose a second. (he puts

down the receiver). Thank God! if only I could

stop the news from leaking here. |

|

Wilbur. |

(returns) Well, Joe, what's

the joke, all alone at this witching hour?

Conjuring demons of the pit, or is this mystic

moment sacred to D-e-reams of Her? |

|

Joe. |

(trembling with excitement)

Just a small business detail; Bill. (He leans

back on couch, exhausted). |

|

Tim. |

(returns—he is badly

burnt). Oh, what an awful, awful thing. |

|

Joe. |

All right for you, old

chap. Rescued the blonde heiress, wedding bells,

what ho! |

|

Tim. |

(earnestly) Joe, don't say

such a thing. It's too terribly shocking. |

|

Joe. |

What is? The dressing gown?

Suited her, I thought. |

|

Tim. |

I don't know if I ought to

tell you. |

|

Wilbur. |

That means you want to—out

with it. |

|

Tim. |

(beckons them, talks in a

tragic whisper) When I climbed up into her

bedroom— |

|

Wilbur. |

Oh, you gay Lothario. |

|

Tim. |

Hush, Bill, it's too awful.

There was a man's clothes all over the room, and

he was running out of the door all undressed. |

|

Wilbur. |

Tut, tut! who was it? |

|

Tim. |

It was Rocco, the

chauffeur. |

|

Wilbur. |

Well, he won't talk, and we

won't talk, and the clothes are burnt, so

where's the harm? |

|

Joe. |

(with sudden anger). Mind

you don't talk! |

|

Tim. |

I hope we are all

gentlemen. (A pause). |

|

Joe. |

I've had enough excitement

for one night. Beat it, boys, and be around in

the morning to see these people somewhere; I'll

be busy. |

|

Wilbur. |

Goodnight Joe, sleep well;

may no ill dreams disturb thy rest, nor powers

of darkness thee molest! |

|

Tim. |

Goodnight, Joe! |

|

Joe. |

(gruffly) 'night. |

|

|

(He sits up, thinking hard,

while the Scene drops). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(The same Morning). |

|

|

(ENTER a doctor. Joe still

sitting, though asleep). |

|

|

|

|

Doctor. |

Morning, Mr. Davies!

Dropped in for another look at my patients. |

|

Joe. |

(yawns) Oh yes! |

|

Doctor. |

That chap Tim Jones is a

hero if ever there was one. He had some shocking

burns. Wasn't content with rescuing Miss Gopher;

pulled out Emily, under-housemaid, and was

caught badly. However, he'll do. |

|

Mrs. Harper. |

(ENTERS, very proud and

dignified and self-possessed despite her

attire). Good-morning, Mr. Davies. I presume I

ought to thank you for your kind hospitality. |

|

Hoe. |

Not at all, Madam, glad if

I have been of service. |

|

Doctor. |

I'll see to my other

patients—nothing wrong with you. |

|

Mrs. Harper. |

I wonder if my companion,

Miss Grey, is all right. She is a perfect

treasure. |

|

Joe. |

I believe she may be in the

next house. No one was burnt but your husband. |

|

Mrs. Harper. |

O yes, poor Samuel. I must

catch the noon limited for New York for my

blacks. Do you think his stocks will go down,

Mr. Davies? |

|

Joe. |

Indeed no, Madam, just a

point or two today and tomorrow, perhaps—but

they're sound, they'll recover. They're based on

genuine value. This bear attack of ours—I say

ours, Madam—has been

fundamentally——ah——factitious. |

|

Mrs. Harper. |

Oh! I'm so glad. Now

where's Adela? I must give her some

instructions. |

|

Joe. |

I think I hear footsteps.

It is possibly her. (Goes to window). A slight,

carroty girl? |

|

Mrs. Harper. |

That must be she

(very strong on the "she"). |

|

Joe. |

(opens door) Come in,

everybody. |

|

|

(Tim, bandaged, with Emily

on his arm, comes in. Following them are the

Editor of the Phippsville Post, a

voluble, nosey, sniffy old man with the popular

touch, and Adela Grey). |

|

Editor. |

Ah! Mrs. Harper, so glad to

see you so well. Terrible, terrible,

bereavement, leading citizen, recent activities

in the market, terrible. Three column splash. I

have been questioning Miss Grey about some of

the details, wished to avoid harrowing your

feelings, Mrs. Harper. Ah! good morning, Mr.

Davies, how's business? Great news this morning

for the bears, eh? Now Mrs. Harper perhaps—do

recline, Madam!—perhaps you might give me a few— |

|

Mrs. Harper. |

Please ask Miss Grey in her

spare time! Adela, send someone at once to town

for some clothes; book a section of the Noon

Limited for New York; call up my hairdresser and

have an appointment made as soon as she opens;

tell Rocco to bring a car out here from the

garage—the Rolls Royce—the black, of course. Why

didn't you think of all this yourself? |

|

Adela. |

I did, Mrs. Harper,

everything will be here in a few minutes. |

|

Mrs. Harper. |

(to Joe) There, I told you

she was a treasure. |

|

Wilbur. |

(ENTERS by window) Treasure

seekers! Wrecked on Joe Davies, Pirate

Island—Hullo! (he breaks off, astounded at

seeing Adela). |

|

Mrs. Harper. |

I don't know who you are,

sir. Do you know Miss Grey? |

|

Wilbur. |

This—(goes to Adela) Never

saw her before. Miss Grey, no! Miss Madder Lake

and Cadmium Orange! |

|

|

(Adela goes impulsively to

him, they shake hands). |

|

Editor. |

(feeling he's losing the

stage) Ahem! Ladies and gentlemen, I think this

the propitious moment—I say it in no spirit of

idle camouflage—the propitious moment, I say to

give expression to your very right and very

natural feelings in the matter of our local

hero, Timothy Jones. I need not dilate upon the

magnificent services which he rendered in view

of the total and most lamentable—and I say it

with all due reserve—most reprehensible failure

of the local fire brigade politics! how many

crimes are committed in the name-leader on that

by the way. Timothy Jones, I repeat, the gallant

rescuer, the wounded soldier of humanity, the

merciful knight, the stainless chevalier sans

peur et sans reproche. Now as I say, such men

should have statues, should be sung by poets,

painted by painters— |

|

Wilbur. |

(interrupting) God forbid! |

|

Editor. |

Don't interrupt, sir. You

gave me the first news of the fire, and here's

the dollar I promised you. (Flings it at him).

And now begone. Ladies and Gentlemen, I feel all

too deeply the unworthiness, the inadequacy, of

any words of mine to do justice to Timothy

Jones. I can but propose that our admiration

take the ah . . . highly practical form of a

testimonial collected on the spot. Now then,

everybody. |

|

|

(He goes around, getting

offers quietly. Mrs. Harper shrugs shoulders). |

|

Mrs. Harper. |

What a bore these persons

are. |

|

Blanche. |

(entering) There seems to

be quite a crowd. I came to Phippsville for

peace, too. Horrid place! Oh, Mr. Davies, good

morning. (very supercilious). |

|

Joe. |

I trust you slept well,

Miss Gopher? |

|

Blanche. |

(ignoring him) Where's that

nice painter man?—Whew. |

|

|

(She sees Wilbur, who has

gone into a corner with Adela. They are

kissing). |

|

Mrs. Harper. |

(turns and sees them) Miss

Grey, what on earth does this mean? Quit my

service this instant. |

|

Adela. |

I did, Mrs. Harper. I am

going to Paris to live with Mr.—Mr.—this

gentleman. |

|

Mrs. Harper. |

What! |

|

Editor. |

Now, Miss Gopher, what may

I put down for—? |

|

Blanche. |

I make it up—whatever it

is—to a thousand dollars. |

|

Tim. |

Then Emily will be mine. |

|

Mrs. Harper. |

Emily! are you all mad? |

|

Emily. |

Begging your pardon, Ma'am,

this gentleman saved my life, and the least I

can do is to make him happy. So, when he asked

me to marry him, I said I would. |

|

Mrs. Harper. |

Good gracious—two

marriages! What next? |

|

Adela. |

Excuse me, Mrs. Harper, but

Wilbur and I do not mean to get married. |

|

Wilbur. |

It's just an ordinary love

affair. The regular thing. |

|

Mrs. Harper. |

Mr. Davies! am I to be

subjected top these insults in your house? |

|

Joe. |

(bewildered) I think it

must be a joke, Mrs. Harper. |

|

Mrs. Harper. |

And abominably bad taste! |

|

Joe. |

You don't take stock in

anything but pictures, do you, Bill? |

|

Wilbur. |

You said it. This is my

favourite Titian. This is Rembrandt's wife, and

Rosetti's, this is Leonardo's ideal, and

Whistler's mistress. This is colour and form

incarnate for a second in one image of love. I

only live for love; I am love's servant, gentle

page of Lady Aphrodite foam-born, glaucous,

inaccessible for ever to all men, but most of

all to those who have possessed her! |

|

Adela. |

This is—just—my—man. I've

been looking for one, strange as it may appear

to you. |

|

Mrs. Harper. |

Please turn these creatures

out! |

|

Joe. |

Here is your car, Mrs.

Harper. |

|

Mrs. Harper. |

In high time. |

|

|

(Wilbur and Adela go off

dancing. The Editor, overwhelmed by events,

stumbles out, helping Mrs. Harper. Tim follows

arm-in-arm with Emily.) |

|

Blanche. |

Coming, Aunt (To Joe.) I

must thank you for your hospitality, my good

man; I shall endeavour not to forget it. |

|

|

(Joe smiles impudently). |

|

Blanche. |

Well, what is it? |

|

Joe. |

Four words with you. |

|

Blanche. |

That's four. |

|

Joe. |

Four more, then. |

|

Blanche. |

You're a presuming person.

(calls) Drive home, Aunt, and send Rocco back

for me. I've something to say to Mr. Davies. |

|

Mrs. Harper. |

(without) All right; in

about forty minutes. |

|

Blanche. |

Well now? (Bell rings) |

|

Joe. |

Excuse me a moment, Miss

Gopher, but I know what the call is, and I've a

hunch it's all right. (Goes to 'phone). Pamela?

Yes, speaking . . . . . Good; I thought so. I'll

be down in an hour or thereabouts. (Rings off).

Sold Harper's stuff short on the first news of

his death; covered at once, cleaned up a million

dollars. |

|

Blanche. |

Is that what you had to say

to me? |

|

Joe. |

No. |

|

Blanche. |

What then? |

|

Joe. |

In four words—Will you

marry me? |

|

Blanche. |

You impudent puppy. Take

your million and buy yourself a shopgirl. |

|

Joe. |

No, it's you, Miss Gopher.

Yes or no? |

|

Blanche. |

In four words—No, no, no,

no, why did I wait to hear this nonsense? |

|

Joe. |

Four words more. Rocco has

confessed everything. (a pause). |

|

Blanche. |

Pah! How much do you want? |

|

Joe. |

Just you. |

|

Blanche. |

And my five millions. |

|

Joe. |

It will be useful. |

|

Blanche. |

You low dirty dog. |

|

Joe. |

Look here, Miss Gopher, no

more of that. It doesn't get anywhere; it's not

business. Now, Blanche— |

|

Blanche. |

Merde. |

|

Joe. |

I don't talk German. Here,

I told you a lie, and it's bad policy, always.

Here's the straight story. Timothy Jones told me

and Wilbur. Wilbur is off to Paris and has

forgotten it by now, and wouldn't talk anyway.

Tim won't talk; besides, I'll take him into the

house at a thousand a year. Rocco won't talk;

you can keep him on to run the cars, if you

like—d'you think I care, you low slut. But I

will talk, you bet your sweet life, unless you

marry me. Now, think it over; isn't that a

clean, sweet airtight, copper-riveted business

proposition? |

|

Blanche. |

(very slowly) You low dirty

dog. |

|

Joe. |

I warned you once. (he

takes her arm and begins twisting it. Slowly as

he twists) Will you marry me? |

|

|

(Blanche endures the agony,

biting her lips). |

|

Joe. |

Will you marry me? |

|

|

(Blanche begins to moan). |

|

Joe. |

Will you marry me? |

|

Blanche. |

(turns and strikes him in

the face with clenched fist) Yes, I will, you

swine. |

|

|

(Joe clutches her, kisses

her savagely, flings her on the sofa). |

|

Joe. |

(rings 'phone). Main 298.

That you, Pamela? Davies speaking. Ring up some

wide-awake church, will you, and have 'em send

round a minister quicker'n the devil. |

|

|

(Rings off, sits on sofa,

lights cigar. Both remain absolutely quiet while

the curtain falls very slowly). |

|

ACT II.

|

|

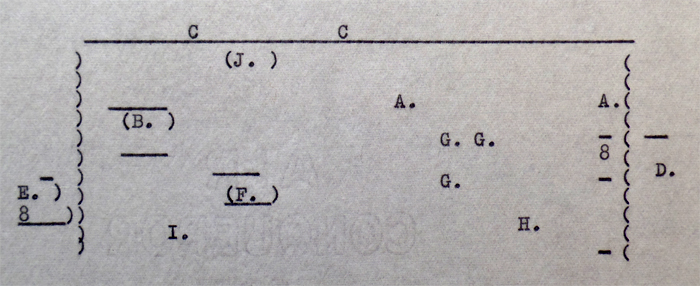

A. A. |

Stairs to gallery and

bedroom. |

|

B. |

Stove to warm models. |

|

C. C. |

Windows—top lights. |

|

D. |

Fireplace. |

|

E. |

Door. |

|

F. |

Easel. |

|

G. G. G. |

Divans beneath stairs and

before fire. |

|

H. |

Armchair. |

|

I. |

Stool. |

|

J. |

Dais for models. |

|

|

Rough chalk sketch begun on

easel; many canvases and a frame or two round

walls. No pictures of any sort to be shown. |

|

|

|

|

|

(Joe is in vigorous prime,

smartly dressed in a lounge suit. Age 35.) |

|

|

(Tim is fat, middle-aged,

looking more servile than ever. Age 35.) |

|

|

(Wilbur is hardly changed

from Act I. Age 35.) |

|

|

(Blanche is over-dressed

and bejewelled, in a very daring evening frock.

She is much painted, tending to over-plumpness,

but still of brilliant beauty. She is fairly

drunk.) |

|

|

(Emily is thin, fallen

away, faded, in middle-class, motherly dress.) |

|

|

(Adela is dressed in a

black frock, as worn by the market girls of

Paris. She looks no more than 25; radiantly

beautiful in the most perfect taste.) |

|

|

|

|

(Wilbur's studio in

Montmartre. A large room, a poor man's room, but

made cunningly comfortable. After dinner, Joe,

Tim, and Wilbur, with Blanche, Emily and Adela

Grey). |

|

Joe. |

Well, Bill, I'll say this:

I never ate a better dinner. |

|

Wilbur. |

Oh, yes you did! The food

wasn't specially good; what you enjoyed was

appetite, and that came from the walk up the

Butte, and the view! |

|

Tim. |

Yes, these are the

compensations of the poor. |

|

Wilbur. |

Rich, Tim, rich as Joe!

What can all this money show him finer that

Paris town? There, to the right, the Trocadero

and the Eiffel Tower; then the Invalides, the

greatest tomb in Christendom, crowned by the

Lion de Belfort, the unconquered of 1870, who

was to wake again and be avenged in 1918. Then

the eye catches the Observatoire, and the long

avenue and garden, like a poem of Verlaine's to

the Luxembourg and the Pantheon, where France

has laid her mightiest dead. There is the Latin

Quarter, where unknown great men live and love

their lives away. There's Saint-Sulpice, whose

architect threw himself in despair from the

tower of his unfinished master-work, and

Saint-Germain-des-Pres, God-house of ancient

cloistered fame. Now through it all the Seine

winds like a silver snake among dark pebbles,

and leads the eye to Notre-Dame, wonder and

glory of the world! |

|

Adela. |

You must excuse the bad

boy; he takes these fits at times. |

|

|

(Blanche is gazing at

Wilbur, enthralled, obsessed). |

|

Joe. |

I think it was a very

striking speech. I didn't know people felt like

that. |

|

Wilbur. |

What has your life to offer

in comparison? |

|

Joe. |

I suppose the bottom of it

is that I like to see my will prevail. |

|

Adela. |

Then you should never have

married. |

|

Blanche. |

Laughter and applause. |

|

Adela. |

I admit it was a silly

thing to say. I am sure you are a model wife. |

|

Blanche. |

I understand that you are

yourself—a model. |

|

Adela. |

But I pose comparatively

little, and I don't paint at all. |

|

Blanche. |

Sallow skins don't take it

well. |

|

Adela. |

And white ones show it too

much. |

|

Joe. |

(very vigorously) As you

were saying, Bill, that's a bully view. What did

you think of it, Tim? |

|

Tim. |

Oh, I couldn't see much of

it, sir—Joe. It was all very pretty, of course,

but I could only see that dreadful fire in the

big store. |

|

Wilbur. |

Yes, by Jove. |

|

Joe. |

Yes what? |

|

Wilbur. |

Why, it sprang into my mind

that the last time we six were under one roof

was the night of the big fire. |

|

Blanche. |

Did you expect me to forget

that? |

|

|

(Wilbur startled at her

earnest tone). |

|

Adela. |

It was the night before I

met my lover. |

|

Joe. |

(anxiously) Well, what of

it? |

|

Wilbur. |

What of it? That's the

night we got our Three Wishes

(mischievously)—and our three wives. |

|

Blanche. |

Two of you. |

|

Joe. |

Come on, Bill, what's the

big idea? |

|

Wilbur. |

I was just wondering if

that wish business would be repeated. Three

time, the fairy said. |

|

Joe. |

Bill, you don't for one

moment seriously believe in that sort of stuff,

do you? |

|

Wilbur. |

Joe, I do. In this corrupt

age there is no way for a man to prove his faith

except by betting on it. Therefore, I hereby (a)

which for the sum of One Dollar and (b) propose

to earn it by betting you that sum that you make

a million dollars between now and midnight. |

|

Joe. |

You silly ass. It's

impossible, You can't make money where there

isn't any money to make. |

|

Wilbur. |

Never mind: only one

proviso, that you take a chance if it comes. |

|

Joe. |

Sure, but it's impossible.

Nobody even knows I'm here. |

|

Wilbur. |

Is it a bet? |

|

Joe. |

If you say so. (They shake

hands). |

|

Adela. |

He certainly is game to

take a chance. |

|

Blanche. |

Some people will grab

anything. |

|

Adela. |

Some people are sorry when

they've got what they grabbed. |

|

Blanche. |

Some people have sense

enough to let it go again. |

|

Joe. |

What in the Devil's name is

the matter with you two women? |

|

Blanche. |

A matter of taste. |

|

Adela. |

No matter. |

|

Joe. |

It's a mystery to me. |

|

Blanche. |

Most things are. |

|

Joe. |

Now what does she mean by

that? |

|

Adela. |

Mischief. |

|

Wilbur. |

Now listen, Joe. Mrs.

Davies said a whole lot then. Most things are a

mystery to him. Do you know that there is a

definite equation between time and greatness?

The earth seems to be always changing its place,

but time shows that it moves in a more or less

unchanging cycle. So do the fixed stars, if you

take a long enough period. Now you can only

recognise a cycle as such by repeated

observation of it. We only know a thing when we

have gone round and round it, and round again.

Joe understands very well indeed the movements

in his tiny circle of business. I, in the

immense cycle of art, am still half lost in

wonder as each new phenomenon bursts upon my

gaze. It will take countless centuries for me to

be the master of my cycle as Joe is today of

his. This low man goes on adding one to one, his

hundred's soon hit; that high man, aiming at a

million, misses a unit. |

|

Joe. |

Ah, I aimed at a million,

and Bill at a unit. Ha, Ha! |

|

Blanche. |

You poor fool. |

|

Wilbur. |

Can't get outside that

cycle, Mrs. Davies. |

|

Blanche. |

Thank the Lord I was never

in it. |

|

Adela. |

We of finer clay feel

otherwise, don't we, Mrs. Davies? |

|

Blanche. |

We artistic people. |

|

Joe. |

(desperately) I don't see

my million tonight, anyhow. |

|

Tim. |

(anxious to help keep

peace) And shall I get my thousand? |

|

Blanche. |

You're always in debt; it's

incomprehensible to me; a thousand a year and

all found and you're in debt. |

|

Tim. |

It's the children, madam. |

|

Joe. |

Damn it, Blanche, you're

always in debt, too! |

|

Adela. |

How lucky to have a

millionaire for a husband! |

|

Wilbur. |

Oh, it's nature's way. It's

the children of the Tim's that make the millions

for the Joes. Why Tim himself founded your

fortune, old boy! He brought the news of

Harper's death. |

|

Joe. |

He didn't know how to use

it. But I was grateful; I gave him a competence

for life. |

|

Wilbur. |

How do you feel about it,

Tim? |

|

Tim. |

I'm very comfortable, thank

you, sir. (A knock). |

|

Wilbur. |

Now, by my fay, who knocks

so late? |

|

Walter Nevill. |

(without) May I come in for

a second, Wilbur? |

|

Wilbur. |

Sure thing. (aside) Walter

Nevill from the Embassy. (open door). |

|

|

(ENTER Blanche.

Introductions—for Joe is in the corner in the

dark. He comes forward). |

|

Nevill. |

Mr. Davies! This is plain

providence. Do you know, Mr. Davies, I have ten

messenger boys out this minute looking for you.

(takes out watch). At the eleventh hour—and

twenty minutes, Ladies and Gentlemen, I'm going

to be most awfully rude. Do excuse Mr. Davies

and myself for about five minutes. It's life and

death. |

|

|

(All retire, Wilbur smoking

his pipe on the settee, Blanche gazing at him

eagerly. Adela quietly embroidering, Tim and

Emily blotted out as ever). |

|

Joe. |

Well, Nevill, what's the

news? |

|

Nevill. |

Oh, it's an option on

building lots. Half a million dollars—expires at

midnight. My man got cold feet this morning, or

he's really strapped, as he says. I offered the

man, Gans, the banker, ten thousand francs for a

three-days extension and he turned me down. The

secret is—the Government want those lots for

barracks—we've been working secretly for it, you

understand, and Gans has got wise to it. I can

sell at a big profit tomorrow. |

|

Joe. |

Where do I come in? |

|

Nevill. |

You help me to take up

option—four hundred thousand is wanted—and . . . |

|

Joe. |

I clear? |

|

Nevill. |

(figures on paper) A

million dollars. |

|

Joe. |

I know you, Nevill, but if

you were the most obvious con man in the

profession I should write you a cheque.

(mysteriously) This is the night of the big

fire. |

|

|

(Nevill, misunderstanding,

laughs). |

|

Wilbur. |

Converted, by Jove! |

|

Joe. |

(takes out notebook and

cheque book). Put it there. |

|

|

(Nevill writes contract and

Joe cheque. They exchange). |

|

Nevill. |

But, damn it, how can I get

there before twelve? Gans lives at 96 Boulevard

Haussman, but there's no taxi within a mile of

here, and the brutes won't come up the hill. |

|

Tim. |

(advances) Excuse me, sir,

but I, that is, Emily thought Mrs. Davies might

be tired and I took the liberty of having the

Napier sent to the door. |

|

Emily. |

(at window) Yes, sir, she's

there now. |

|

Joe. |

Tim, you've done it again!

Here and now I announce publicly my belief in

fairies, and I present you with the sum of 1,000

dollars. (pulls it from his wallet). Now Tim,

put Mr. Nevill in the car—plenty of time! |

|

Emily. |

Perhaps Tim and I had

better go home to see if all's right in the

house, madam. |

|

Blanche. |

Yes, you had. |

|

Joe. |

And more solemnly still, O

Wilbur Owen, I present you with this dollar, won

in honest betting. |

|

Nevill. |

A thousand thanks, Davies.

I'll be off. By the way, Wilbur, I nearly forgot

what I came up for. I want you to drop in at the

Embassy first chance. The Government are making

you their expert in that art business—so you're

a dollar a year man now. |

|

Wilbur. |

The Three Wishes! |

|

Nevill. |

(misunderstanding) Health,

Wealth and Happiness! |

|

|

(He takes his leave and

goes out with Tim and Emily). |

|

Blanche. |

(very slowly and clearly)

I've been wishing too, wishing I had come in

that room about ten minutes before I did. |

|

Joe. |

Damn it, Blanche, are you

making love to the man before my eyes? |

|

Blanche. |

Now that you have exhibited

your well-known force of character, perhaps you

will rest the afflicted part. So if you've got

anything else to say, shut up! |

|

Joe. |

Remember where you are. |

|

Blanche. |

I've borne too much;

tonight I'll cut loose. |

|

Joe. |

Borne? What have I borne?

Constant intrigues with Dagoes, Niggers, Airmen,

Pianists, Tango-lizards— |

|

Blanche. |

Never with you! |

|

Joe. |

Do I care? What did I want

you for? |

|

Blanche. |

My money! |

|

Joe. |

Your lawyers looked damned

well after that. And yet you're always running

after me for money. What do I pay it for?

Blackmail! |

|

Blanche. |

More reason and justice for

you to pay it—the blackmailer blackmailed! |

|

Joe. |

Was there any other man you

could get? When the night before our marriage

you were caught with a wop chauffeur! |

|

Blanche. |

Only a blackmailer. |

|

Joe. |

Quit that, you dirty dyed

street walker! |

|

Blanche. |

You low—dirty—dog! |

|

Joe. |

(he catches her arm). You

can't do it again and get away with it. |

|

Blanche. |

Nor can you, now that I

know what the Law is. (She brings out a gun and

points it at him). I should love to put a slug

in your greasy guts, you hound! |

|

Wilbur. |

Please don't, Mrs. Davies,

not here. They are crazy about these things in

France—no end of trouble if you shoot a man. Go

to Long Island! |

|

Blanche. |

(wrenches herself away)

Hell! |

|

Adela. |

Tim and Emily would say

that money does not always bring happiness. |

|

Wilbur. |

Yes, but it brings about

some amusing scenes. |

|

Blanche. |

I wish! I wish—oh, if I'd

been in that room ten minutes earlier. |

|

Adela. |

The early bird again

Blanche, dearest. |

|

Blanche. |

My sweet Adela, the early

sportsman sometimes catches the early bird. |

|

Wilbur. |

Excuse me, ladies, but I

haven't the slightest idea what you're talking

about. Who got into what room and why, and what

would have happened if there had been a Daylight

Saving Act? |

|

Blanche. |

Joe's room, you blind man! |

|

Adela. |

None so blind as those who

won't see. |

|

Wilbur. |

Leave her alone. |

|

Blanche. |

If I'd been in that room

when you came in that morning, you'd never have

noticed that sly quiet cat! |

|

Wilbur. |

I rather like these red

Persians, don't you know. |

|

Blanche. |

I would have loved you all

your life—passionately. |

|

Joe. |

She'll be sober in an

hour—I hope; meanwhile I'll smoke. |

|

Wilbur. |

That is a long time, and an

exhausting manner. |

|

Blanche. |

Are you absolutely callous?

Don't you see what shame I've put on myself? But

I just had to speak—I've loved you all these

years. You've haunted my dreams, you've become

between me and the— |

|

Joe. |

Chauffeurs? |

|

|

(Blanche pulls out her

pistol; Wilbur jumps in, disarms her and puts

the gun out of reach). |

|

Wilbur. |

Don't spoil our nice quiet

chat! These reminiscences of childhood's happy

days. I never had playmates, I have had

companions. |

|

Joe. |

(chuckling) That's blown a

tyre! |

|

Blanche. |

Oh, never mind; you can't

spoil it like that. I love you, I've never loved

anyone else—all these years I've wanted you. |

|

Wilbur. |

That's absurd, really; you

never gave me a thought till we met by chance

yesterday on the Boulevard. |

|

Blanche. |

Ah, you may believe it;

perhaps I didn't know it myself. |

|

Wilbur. |

Now we're getting a but

nearer; we can never tell what the subconscious

is after; and I am awfully, beastly, jolly

lovable, of course. But, that's no reason for

me to love you. |

|

Blanche. |

Don't you admire me—am I

not beautiful? |

|

Wilbur. |

I admire the Cloth Hall at

Ypres—it is beautiful. |

|

Blanche. |

Oh you low dirty dog. I'm

of an age with Adela—twenty-eight. |

|

Adela. |

I'm thirty-four. |

|

Wilbur. |

Pardon me, no; she is of no

age. She is older than the Sphinx, and a long

sight more mysterious. |

|

Blanche. |

These skinny rats look

young till they're fifty and then they wither. |

|

Adela. |

These white guinea-pigs

look fifty when they're thirty-four. |

|

Joe. |

(begins to be thoroughly

amused) Had you there, Blanchy! |

|

Blanche. |

Shut up! Shut up! Will! my

Will—you are my Will—I'll give you a million

dollars if you'll come and live with me six

months. |

|

Joe. |

Here, you're getting the

wishes mixed! |

|

Blanche. |

Grrr! |

|

Wilbur. |

Thank you very much,

Blanche, but I'm afraid I might get to like the

taste— |

|

Adela. |

Of money? |

|

Wilbur. |

Exactly. As I was about to

say when I was rudely interrupted, I might get

to like money—the taste of it—and lose my art.

Do you see, Blanche, when I wished for that

dollar, it was to buy a book of magic spells to

conjure beauty. And I bought it. It was a book

of art, inexhaustible well of joy. And I bought

it. Did Joe buy better value for his million? I

haven't repented my choice; I dine sumptuously

every day—or nearly every day—on air and

exercise. I have the greatest gallery of

pictures in the world. I have Adela. |

|

Blanche. |

Aren't you ever tired of

Adela? |

|

Wilbur. |

Now and again; as one tires

of Goya, Leonardo, Greuze, now and again. |

|

Blanche. |

I wouldn't tire of you———I

daresay you're right, and I only want you for a

little while. |

|

Wilbur. |

Six months I think you

said. Three I might manage. |

|

Blanche. |

Three minutes would be

paradise. |

|

Adela. |

Some snake. |

|

Wilbur. |

Hush, Adela, you've been

cattish about this all the evening. I must say

it isn't like you. |

|

Adela. |

I'm sorry. I beg your

pardon, Blanche, will you kiss me? |

|

Blanche. |

One more or less doesn't

matter. (They kiss). |

|

Adela. |

Now I ought to have said

that. |

|

Blanche. |

Oh, my dear, I'm a fool. I

ought to be glad you've found a great man to

love, to be true to. |

|

Wilbur. |

Wait, wait, you're all in

too much of a hurry. |

|

Blanche. |

I'm sorry, Will, I loved

you. I couldn't help telling you. I love you

more than ever for that speech about the

million. |

|

Wilbur. |

Well, that certainly was a

stumbling block and a rock of offence. I think

we'll cut that out, but I'll go with you. |

|

Blanche. |

Rate! That's cruel, for I'm

serious. |

|

|

(Adela sits down, and

suddenly begins to cry, for she believes him). |

|

Wilbur. |

Adela, this is Freudian.

You have a complex, you are jealous only because

you were subconsciously envious of Blanche years

ago. You haven't been jealous of fifty other

women where cause existed, as it does not

here—at present. |

|

Adela. |

Thanks, Bill, I was a fool.

Go to it. |

|

Blanche. |

Wh—a—t? Do you mean—

(pause. Joe chuckles, thinking Blanche is being

made a fool of). |

|

Wilbur. |

I mean what I say. I,

Wilbur Owen, do take thee, Blanche Davis, to

have and to hold, for richer or poorer, till

three months do us part.

You remind me of an

over-ripe Camembert cheese—which I love most of

all cheeses—and therefore do I love you.

You remind me of the

leaves, as they turn orange and flamingo at the

fall—and therefore do I love you!

You are hot, spicy,

fishy—and thereby remind me of prawn curry, the

best dish of Singapore—and therefore do I love

you.

You remind me of

strawberry shortcake with vanilla ice all over

the top—and therefore do I love you.

You are dressed like a

peacock—a peacock with a white body—and

therefore do I love you.

You smell of musk and

patchouli and Trefle Incarnat and onions and old

brandy—and therefore do I love you.

End of epithalamium:

exeunt. So long, Addie, you see me this day

three months; so long, Joe, take care of

yourself—I'm giving you a chance! Now then, all

things being accomplished by the blessing of

God, I will embrace my lady, and we will walk

forth on our adventure under a starry night! |

|

|

(They come together and

kiss long, voluptuously, intensely). |

|

Joe. |

(on his feet) Can you stand

this? |

|

Adela. |

Why not? It often happens. |

|

Joe. |

That's so (bitterly). Even

in my limited circle, that's so. |

|

Adela. |

Take no notice; keep right

on with the business of life. Follow your own

star; don't worry about eccentricities—real or

apparent—of other people's orbits. |

|

Joe. |

By jove, that's wisdom!

What a business women you would have made! |

|

Adela. |

Perhaps I am one . . .

Here, Bill, break away; what if anyone should

come in your absence to buy a picture? |

|

Wilbur. |

(releases Blanche) Don't

let me hear; I might believe it, and then I'd

know for sure I was asleep. |

|

Joe. |

Bill! do you mean that? Do

you mean to tell me that in all these years

you've never sold a picture? |

|

Wilbur. |

Not yet. But tomorrow is

also a day. I live in hope. What with the high

cost of living and the strenuous life, and

trying to make out what the President's

manifestoes mean, so many people are going

insane that I might sell one any day—and so,

fare thee well, my boyhood's friend! |

|

Adela. |

You'll want some things to

take with you. |

|

Wilbur. |

Perish the thought, kindly

though it be. Blanche and I are going to walk

from this spot, without money or baggage, to

Gibraltar. |

|

Blanche. |

Indeed I'm not! |

|

Wilbur. |

The less need for

preparation. |

|

Blanche. |

I'll go with you to Hell! |

|

|

(They blow kisses to the

others, and walk out). |

|

Joe. |

Jesus Christ! Tamed that

wild cat with a word. Am I going crazy? |

|

Adela. |

Not at all, Mr. Davies,

it's all perfectly natural. Let me mix you

another grog. |

|

Joe. |

Thanks, I guess I will.

D'ye know, this is funny—both of us left

grass-widows, as you may say. |

|

Adela. |

So you are about to propose

to take a villa for me at Deauville? |

|

Joe. |

Say, how d'ye know what I'm

thinking? Never heard of Dougliville—sounds

good, but it was sure my idea. |

|

Adela. |

I know because you're hurt.

God knows why—and that would be about your

primitive idea of getting even. |

|

Joe. |

I suppose that's it. But

you're a damned pretty woman, and I like your

style. Call it on? |

|

Adela. |

Who taught you to woo so

exquisite? |

|

Joe. |

Look here, that's not fair.

I never had no education. |

|

Adela. |

I'm sorry, I shouldn't have

said that; but you complained. |

|

Joe. |

Yes, by God, I do complain.

Here am I, not bad looking, strong as a bull,

healthy as a baby, money to burn, a power all

over the world; and I can't do a thing with two

women who'll just howl with joy for Bill Owen to

tread on them! |

|

Adela. |

It's that cycle, Joe. You

believe there are such things as women. He

doesn't. We're only the moths fluttering round

his big light. He's busy with other things;

women are an accidental to his art. He doesn't

take us seriously. That piques us; we go too

often, we go for wool and come back shorn. But

it's worth it. |

|

Joe. |

All the same, what about

Deauville? |

|

Adela. |

Quite impossible, I fear.

There's an unexpected rush of certain Government

business which keeps two of my paramours in

Paris all summer. |

|

Joe. |

(his jaw drops) Mrs. Owen! |

|

Adela. |

Miss Grey, please; or

Adela, if you like. |

|

Joe. |

Good God! And here I've

been assuming you were true to Bill! |

|

Adela. |

So I am. |

|

Joe. |

What did I hear you say. |

|

Adela. |

I fancy I might have

mentioned paramours. |

|

Joe. |

Yes, paramours; how does

that go with being with Bill. |

|

Adela. |

Truth is the love of heart

and soul. Body goes with them, but its appetites

are occasionally eccentric. Am I unfaithful to

mutton when I eat beef or commit suicide when I

blow my nose? I live for him, I'd die for him,

but I don't see why I should starve myself, and

get into a groove and be dull, and grow old and

ugly, and have him hate me for it when it

wouldn't even please him at the time. Why

amourettes make conversation! |

|

Joe. |

I find this a little hard

to follow. |

|

Adela. |

It's the mountain air of

Montmartre, Joe! Air of freedom! Air of art! Air

of beauty, health, good sense. Damn it,

everybody does it who can; only some of us don't

say so and those who can't kick up a fuss—sour

grapes! |

|

Joe. |

But society . . . |

|

Adela. |

Society the Four Hundred

and Forty Artists and the big four does it.

Leave it for Tim to say that the foundations of

human intercourse quake when a married lady

winks. |

|

Joe. |

That is true, too, now you

say it. But what about my question, why don't

women love me? Say, I'll tell you a secret. I

blackmailed Blanchy into marriage for her money.

Then I fell in love with her; and I never got

anything but contempt. |

|

Adela. |

Bill not only takes no

notice of me, he expects me to take no notice of

him. He treats me as if I were a man, fully

responsible of all importance to my own life,

none at all to his. So we can be friends and

lovers, and live on together. O these ten,

twelve years since passion died! |

|

Joe. |

Blanchy knows all this,

too? |

|

Adela. |

Every woman know this,

either consciously or instinctively. Every man

who knows it takes his pick of us. Notice how

often the toy man, half men, homosexuals,

attract women? That's because they understand

feminine psychology. You did a perfectly foolish

thing tonight, we were both in a diminuendo

passage of our lives, we ought to have been

polite and parted coolly. You can only make love

successfully on the crescendo passages. I should

have thought that Nature herself might have

taught you that. |

|

Joe. |

(shakes his head sadly)

Yep, by heck, some falling market. The wise guys

buy at the bottom, and wait for the rise. |

|

Adela. |

That's better, Joe, I think

I could teach you. You've got the essence of the

thing—manhood. But, you're clumsy, you twist

people's arms on a falling market. Look here!

Blanche wrote me the story of your tactful

marriage proposal. Low dirty dog is what you

were. But all women love dirty dogs. Hence, by

the way, various legends of the Parzival type.

But you got her, not from scare, but because you

tortured her when the market was rising. She was

raging at having her affair with Rocco

interrupted by the fire. She was sexually wild;

so she slapped you and said, “I will, you

swine,” which is actually honest English for the

romantic “Darling, I love you.” If you had raped

her, then and there, she would have loved you.

Instead, you showed that you cared for nothing

but her money. She would have forgotten that if

you had let her. |

|

Joe. |

I see; I ought to have

caught her on the rising market. |

|

Adela. |

See how Bill worked

Blanche. He began by contemptuous indifference,

that put her on her mettle, and all the time he

was exciting her by long romantic speeches, the

artist's point of view, and all that when he saw

how she sucked down the bait. Once he got her

going, he whipped her with insults even bad ones

like ber being old till he made her mad to the

limit. Then he swung round suddenly and snatched

her. Je just tested his sword with that walk to

Gibraltar; it's true tempered steel, he sheathes

it and whistles. She's his spaniel bitch. |

|

Joe. |

Sometimes I think I'm in a

mad house, only all the time there's something

tells me you're right. |

|

Adela. |

Well that's enough: lesson

one for my big dunce. Let's go to bed. |

|

Joe. |

Why, Miss Grey, I'm awfully

sorry to have kept you up to such an

unconscionable hour. (takes hat and cane)

Goodnight. |

|

Adela. |

(sweetly) Goodnight, Mr.

Davies, so dear of you to have looked us up. |

|

Joe. |

I hope I may have the

pleasure of seeing you again shortly. |

|

Adela. |

Indeed, I trust it may be

so. (he is at the door). Didn't you hear what I

said? |

|

Joe. |

(turns sharply) Hear what

you said? |

|

Adela. |

Four words. |

|

Joe. |

Four words? |

|

Adela. |

Let us go to bed. |

|

Joe. |

What d'ye mean? |

|

Adela. |

What I say. |

|

Joe. |

I drank too much, I'm

dizzy. |

|

Adela. |

It's merely that I pity

your ignorance: I should like to teach you how

to win Blanche, for her sake, poor darling; and

that can only be done by person instruction. I

don't love you at all. |

|

Joe. |

(peeved) Nor do I you, Miss

Grey. |

|

Adela. |

Very good, very good. You

see, to men you may seem a power, a monarch, a

monster, a—oh! all sorts of terrible things. To

women you are a big, simple-hearted fool. |

|

Joe. |

(angrily) Am I? |

|

Adela. |

One can take you seriously,

can one? |

|

Joe. |

I'll make 'em. |

|

Adela. |

Good, very good, in theory.

Beware of theorising, Joe, my Joe! |

|

Joe. |

Yes (sits down) Yes,

there's something radically wrong with me.

What's lacking? |

|

Adela. |

Possibly what the late

J.M.W. Turner used to mix his paints with. |

|

Joe. |

What's that? |

|

Adela. |

Brains, Madam, brains. |

|

Joe. |

Damnation! |

|

Adela. |

Well, shall I mix you

another grog? A stiff one? |

|

Joe. |

Stiff nothing. |

|

Adela. |

I'm sorry. Joe . . . I

didn't mean to make you angry. |

|

Joe. |

I'm not angry, I'm just

down and out. I don't know anything any more. |

|

Adela. |

You're tired. Let's go to

bed. |

|

Joe. |

I'm damned if I do! |

|

|

(rushes out of the door and

slams it. Adela takes out her watch and counts

the seconds). |

|

Adela. |

One . . . two . . . (up to

forty four). |

|

|

(Joe rushes in: flings his

hat and cane down). |

|

Joe. |

I'm damned if I don't! |

|

Adela. |

Small chance of salvation

in that case, Joe. You get it coming and you get

it going! |

|

Joe. |

Adela, I love you, I'd die

for you. I never knew what it was to love

before. Come over here! |

|

Adela. |

(in his arms; very sadly

and seriously) Oh Joe, I'm so sorry. I've played

with you, I never thought you'd stay. It's

utterly, absolutely impossible—really and truly.

Yes, you understand, I'm sure. Take me to dinner

two nights from now—will you? |

|

Joe. |

(very affected, drooping,

kissing her listlessly) Sure, I understand,

sweetheart. I'll be here at six o'clock. Take

care of yourself, Honey! Sleep well. |

|

|

(He kisses her again,

patronizingly, and goes out). |

|

Adela. |

And I quite forgot to

mention that I'm going to Deauville with Mimi

Lalangue tomorrow morning! (she breaks into fit

after fit of laughter) I must . . . I really

must. The end of a perfect day! (goes to 'phone)

Clichy 31—69 . . . . .

Non 31—69 . . . . .

Qui! moi-meme . . . . .

Je suis seule! . . . . .

Bon. |

|

|

(rings off; goes to door

and leaves it ajar, begins to undress, humming a

love song). |

|

|

|

|

THE CURTAIN FALLS |

|

|

|

ACT 3. |

|

|

|

|

Joe. |

(age 50) is old, poucy,

haggard, nervous, bloated, bald, very red-faced. |

|

Tim. |

old, fat, stupid, cringing,

white hair. |

|

Blanche. |

a complete ruin newly

decorated by a bad firm. |

|

Emily. |

dowdier than ever. |

|

Adela. |

hardly older than before,

looks at most 35. In rich dark ivy green and

lilac. |

|

|

|

|

The breakfast-room at Joe's

palace on Fifth Avenue. It is over-loaded with

bad pictures, statuary and objets d'art. The

table is a mass of chafing dishes and gold

plate. |

|

|

|

|

Joe. |

going through pile of

letters. |

|

Blanche. |

smoking, in an extravagant

negligee. |

|

Emily. |

waiting at table. |

|

Tim. |

as secretary. |

|

|

|

Joe. |

(passing letters to Tim).

Holz answers that.

No.

No.

Send him a statement.

I'll talk this over with

Holz.

Gol darn it, this is awful.

Look here, Blanchy, you better cut out that

violinist. Do you realize we're paupers? Income

tax, property tax, supertax, assessments; I'll

dies in the workhouse. It's abominable. |

|

Blanche. |

(Languidly but acidly)

There's always my five millions. |

|

Joe. |

Which I made into

thirty-five, don't forget that. |

|

Blanche. |

Well, I suppose I can have

a cheque for the cat's meat man on Saturday. |

|

Joe. |

I guess so. Fact is, they

haven't got on to some of my profits yet. I move

a bit too quick, may be, for the old one-eyed

mules in Washington. |

|

Blanche. |

You were always quick on

the draw. |

|

Joe. |

Yes, I've done well. What's

this? Adela Grey? That's that red-headed wench

of Bill's. Wants to come up and see me this

morning—exhibition over here—can I help arrange

it? Sure, I will. Poor old Bill. God! what a

rotten mess that chap made of his life! Had

brains too, and he never sold one picture, and

died in absolute penury. 'Phone her at the

hotel, Tim, she can come here at ten. Wonder

what she looks like at fifty. |

|

Blanche. |

(sharply) She's not fifty

yet, and she look pretty good, I guess. She had

a real man to love her. |

|

Joe. |

Going through letters

again). Send this on to McGrath. I'll answer

this, and this. Tell Holz never to bother me

with this kind again. No. Yes: Tell him to call.

All right, send Mrs. Brown to the library. I'll

be along. |

|

|

(Tim goes out with the

letters). |

|

Joe. |

Oh yes: Wonder what that

fool president said at the Bankers' Association

last night. |

|

|

(picks up paper, reads and

comments). |

|

|

“President scores wealth” |

|

Joe. |

He would want the

Bolshevik vote in the fall.

“Intolerable

tyranny—malefactors of great wealth—find no

criminal is above the law—organized robbery and

oppression—a treacherous and I believe suicidal

policy—”

Lord, what a

topsy-turvy world we're drifting into for lack

of a little firmness—and vote-catching, damn his

eyes!

“Retribution is

imminent. May I not—”

May he not? He'll get

what the camel got, right in the place where the

camel got it.

“We must tax the

insidious traitors to death; they must be bled

white.” The damn fool—with half the capital in

the country going to England, and the other half

buying diamonds to salt down.

“Wealth is the cancer

of the body politic.” That's what I get. Might

as well have died unknown like Bill. At least he

got a little peace now and again. |

|

Blanche. |

He's at peace now. |

|

Joe. |

Oh, sure! But I like a

fellow who makes his mark. He's dead and rotten;

and not half a dozen people remember him. |

|

|

(turns page of paper). |

|

Joe. |

“Big fire in Chicago. Eight

hundred burnt alive—” All right—nowhere near our

interests—

“France honours

America's greatest son”

Not me—”though I did

get the Old Legion of Honour.

(appalled—) Wilbur

Owen!

(calmer) That can't be

our Bill! |

|

Blanche. |

Suppose you were to read

it? |

|

Joe. |

“The greatest since the

Renaissance,” whatever that was— “the pure

genius of his immortal conception in unsullied

by any flaw; Our own great Rodin” — Blanchy

dear, this is the speech of the President of the

French Republic— “our own great Rodin had

neither his vigor nor his mastery of form. The

American Eagle came to the Eyrie of the French

Eagles—and the stranger looked upon the sun with

lidless eye undazzled as no man had done since

Titian and Michael Angelo. Son of the morning!

Time bows her laurelled brow before thy

conquering falchion; France, nurse of Art, thy

foster-mother, confirms upon thy forehead the

wreath of bays immortal that thy fingers twisted

for thy coronal.” This is Bill! This is the

President of the French Republic on Bill!

(sarcastically) The idea is a simple one. Bill

became a French citizen; so we'll put him in the

Pantheon. As an American born, won't America

join in the celebration? Like Kelly will.

And here's our boob

President's cable.

“May I not be the

first—”

Oh damnation, what a

rotten world! |

|

Blanche. |

You always hated Bill; you

were always afraid of him; you knew in your

heart that he was a better man. |

|

Joe. |

The hell I did!

—“Death doubly

lamentable in that it leaves no man worthy to

raise a fitting monument over the mortal part of

him.”

Oh — oh — oh! |

|

|

(He is attacked by

apoplexy). |

|

Blanche. |

(screams) What's the

matter?

(screams again and again)

Help! the master's sick. |

|

|

(Emily and Tim rush in). |

|

Emily. |

Ring for the doctor, Tim! |

|

|

(She tends Joe. Blanche in

violent emotion of several kinds—on the point of

a breakdown. Time phones). |

|

Emily. |

I'm afraid this is a bad

business, madam; my brother went that way last

year. |

|

Tim. |

I got him just as he was

starting. He'll be around in a minute. |

|

Blanche. |

A minute! a minute! I'm in

eternity, and I'm a damned soul. I'm thirsty. |

|

Tim. |

Drink some water, ma'am.

I'm sure you'll feel better. |

|

|

(Blanche drinks

convulsively, and sits down, calmer. A little

more mistress of herself, she pulls up her dress

and injects Morphine in her thigh). |

|

Tim. |

That's the doctor, ma'am. |

|

|

(goes to admit him). |

|

Dr. |

Good morning, Mrs. Davies.

Ah, I see——tut-tut. (Examines Joe). |

|

Blanche. |

That means he's dead. I

thought so. |

|

Dr. |

I warned him less than a

month ago that he had a tendency to apoplexy.

Too much breakfast—some unusual excitement—ah

well, we must all go one day. |

|

Blanche. |

Thank you very much for you

tactful consolations. Can the body be moved to

the bedroom? |

|

Dr. |

Certainly, of course. I'll

sign the certificate at once. There'll be no

trouble. |

|

Blanche. |

(lighting a cigarette). I

am much too prostrated by grief to attend to

anything. Tim, ring up Mr. Holz, and have him be

careful about how the market takes the news, and

then he can come round here and see to

everything. Good morning, doctor. |

|

Dr. |

Good morning, madam.

(goes). |

|

Blanche. |

(mysteriously). Come back,

Tim, when you've phoned. |

|

Tim. |

Yes, Ma'am. |

|

|

(He goes. Blanche very

restless, gives herself another shot of

morphine. Tim returns with two footmen, who

begin to remove the body). |

|

Blanche. |

You've got the combination

of the safe, Tim? |

|

Tim. |

Yes, but he had the key,

ma'am. |

|

Blanche. |

They used to be on a chain.

Ah, here they are. |

|

|

(the men remove the

corpse). |

|

Blanche. |

Get the will out, Tim. |

|

|

(Tim opens the safe, and

finds will, and brings it to her. She reads). |

|

Blanche. |

Oh, that's alright, that's

fine. What's this? Oh he surely had a sense of

humour. He insured himself for a million, so

that he should make that even by dying—and he

left poor old Bill a dollar, and you a thousand,

Tim. |

|

Tim. |

Very satisfactory, I'm

sure, Ma'am. |

|

|

(he moves around, very

nervous, restless, distraught, as if he had

something on his mind. A long pause for this). |

|

Tim. |

May I say something very

frankly, madam? |

|

Blanche. |

You may, Tim, if it's not

very long. |

|

Tim. |

Have I given satisfaction

to you and the master, madam? |

|

Blanche. |

You bet you have! You have

been honest, loyal, obedient, diligent,

uncomplaining, faithful, truthful, careful,

accurate, mindful, Jesus Christ, I never knew

there were so many virtues, and you've got 'em

all. |

|

Tim. |

Yes, ma'am, I believe I

have. And I can't stand it any more. Everything

I do seems to turn to a thousand dollars. This

last is the crusher — and — having no master. |

|

Blanche. |

Yes, whatever you had, you

would never have anything, because there's no

you to have it. You're only a copy-book with

noble precepts beautifully printed—and not even

a child to scrawl over it. |

|

Tim. |

Indeed that's true, ma'am.

If I've served you well, may I ask you one

favour? |

|

Blanche. |

I will not, positively will

not——kiss you, Tim! |

|

Tim. |

Indeed, Ma'am, Emily

wouldn't like it if you did. I only wanted—tell

me, isn't there an easy way to die? |

|

Blanche. |

Easier than living, Tim. Oh

yes, death is a delicious delirium when you know

how. |

|

Tim. |

Is that — — — — |

|

|

(He gasps with fear at the

thought of a ‘drug’). |

|

|

— — — — morphia? |

|

Blanche. |

It is, Tim. |

|

Tim. |

May I—may I—have some—just

enough, you know— — |

|

Blanche. |

Sure, take some of these

tablets. Four now, six when you begin to feel

sleepy. Gorgeous dreams, and never wake up! |

|

|

(gives pills). |

|

Tim. |

Thank you, ma'am, thank

you! I humbly take my leave. I'm glad I've given

you satisfaction, ma'am. |

|

Blanche. |

Goo' bye, and goo' luck:

Say, look here, don't die about the house. Take

a room in a hotel. I can't have my home all

cluttered up with corpses. |

|

Tim. |

Yes, ma'am. |

|

|

(he goes out). |

|

Blanche. |

(yawns) I think I'll wear

my Hungarian today; or shall it be my man from

the Sicilian Players? Perhaps it would be more

proper to go straight into full mourning. Oh,

I'm so tired of men! |

|

|

(injects herself). |

|

Blanche. |

So tired. |

|

|

(a knock. Enter footman). |

|

Footman. |

Excuse me, ma'am, there's a

Miss Grey here, who had an appointment. I told

her the news, and she requested to see you,

ma'am. |

|

Blanche. |

Now that's really

amusing—shew her in. |

|

|

(he goes. Blanche darts to

the mirror and powders herself, etc.) |

|

Footman. |

(returns). Miss Grey! |

|

|

(Adela walks in). |

|

Blanche. |

Adela, you sweetest thing,

how well you look! |

|

Adela. |

My darling Blanche, you're

lovelier than ever. |

|

Blanche. |

Oh, I am so glad to see

you! |

|

Adela. |

Indeed there's no friends

like old friends, though we did have our

quarrels. |

|

Blanche. |

I've nothing but love for

you, dearest. |

|

Adela. |

I wish I'd been kinder to

you. |

|

Blanche. |

Oh, do sit down,

sweetheart, and let me tell you all about Joe

dying this morning. |

|

Adela. |

Oh, I should just love to

hear it. |

|

Blanche. |

It was all your fault,

really, for you did everything to make Bill what

he was. So, when Joe heard Bill, whom he

despised for a fool, called America's greatest

son, he just got apoplexy. What a lovely dress

that is, dear! |

|

Adela. |

Yes, it's Doucet. My

circumstances have changed a good deal since

Bill died, of course. The dear boy was hardly

dead three months, before they discovered him.

It's been a fury of work, but I've put him where

he belongs—with the great Gods that pity men and

come to live among them. He liked me best in

ivy-green and violet, because of my hair. |

|

Blanche. |

He liked me best in

beggar's rags. |

|

Adela. |

I wish you'd tell me that

story one day. I never asked Bill what happened,

nor let him tell me. I had a feeling about it;—I

can't explain it. |

|

Blanche. |

I can, he really loved me

for a few minutes. You see I had been lording it

over men all my life, and the wild beast in him

wanted to tame me, hurt me, humiliate me,

trample me. |

|

Adela. |

I see. And you liked it? |

|

Blanche. |

What woman wouldn't? I know

lots of suffragettes who'd give their ears to be

kicked by a navvy. |

|

Adela. |

No; some women can't enjoy

anything. The Emily type. |

|

Blanche. |

Women! The world's full of

blind, deaf, senseless, sexless, soulless

worms—the Emily type! I don't call her a woman. |

|

|

(a knock). |

|

Blanche. |

Come in! |

|

Emily. |

(in great agitation). Oh. I

beg your pardon, ma'am, most humbly, but is Tim

here? Has he gone out? |

|

Blanche. |

Your agitation appears to

betoken some distress. |

|

Emily. |

I've a letter of farewell,

ma'am, from Tim, and now I can't find him. |

|

Blanche. |

Well, to cut short your

anxieties, Emily, Tim went out of the house

recently. His intention (as I understand) is to

take a room at a hotel, under an assumed name,

and poison himself. |

|

Adela. |

Blanche, how can you? |

|

|

(she goes and comforts

Emily, who is sitting half collapsed trembling

and crying. She is more like 79 than her 49). |

|

Emily. |

How could he? How could he?

After all these years? |

|

Blanche. |

But that's it, Emily;

that's where you pay for your folly in trying to

create a permanent tie in a world of

impermanence! |

|

Adela. |

There's wisdom in those

words, though they seem cruel. |

|

Blanche. |

Emily, did you ever have a

good time in your life? |

|

Emily. |

Oh, Ma'am, nothing ever

happened, and I kind of got used to it. |

|

Blanche. |

Well, I had only one time

which counted, and I was just going to tell

about it when you came in. It was a strictly

temporary good time, by agreement; yes, it was

when Wilbur Owen took me away from Paris. We

walked all night; by sunrise, I was cold and

hungry, and my shoes pinched me—you remember, I

was dressed for dinner—and he was more carrying

me than helping me to walk. |

|