|

TIGER-WOMAN

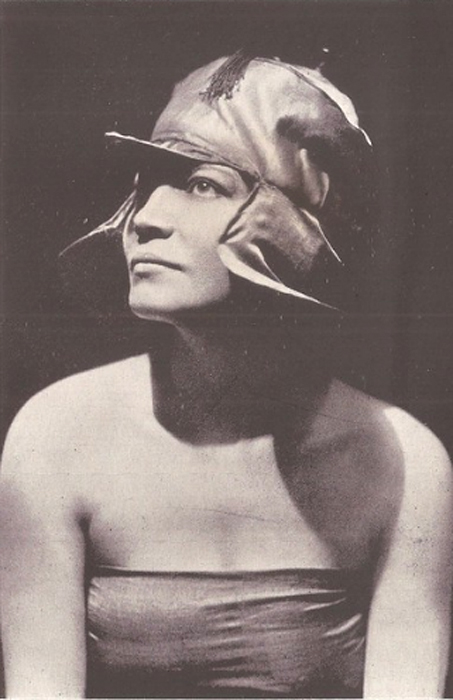

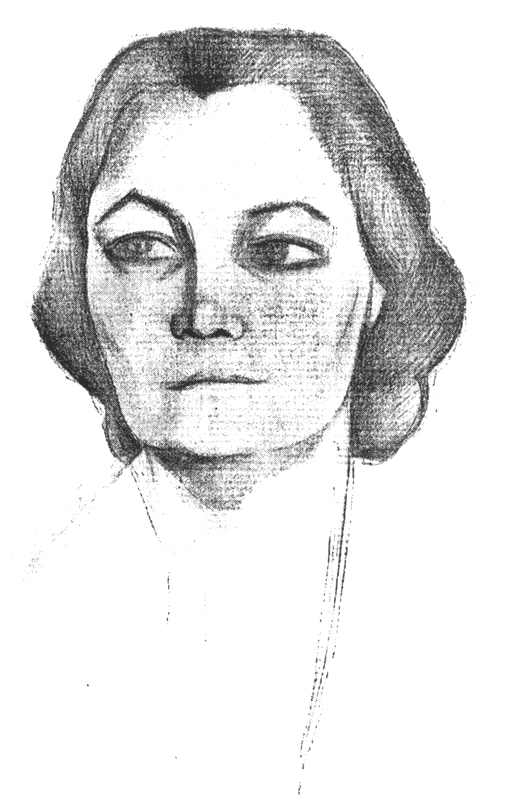

Betty May — “The Tiger Woman”

TIGER-WOMAN

My Story

by

DUCKWORTH 3 Henrietta Street, London 1929

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER I CHILDHOOD Myself—Earliest memories—My coster grandmother—A suicide—I am sent to live with my father—My father’s bad character—His arrest by my grandfather—Life on a barge—I dance for some sailors—I go to Somerset—The schoolmaster—I am sent to London—The beginning of adventures

CHAPTER II THE CAFÉ ROYAL My first night club—Rosie’s wig—A Cambridge undergraduate—The Endell Street Club—I am taken to the Café Royal—Epstein—Augustus John—Horace Cole—Epstein speaks to me—The Cave of the Golden Calf—Madame Strindberg—”The Cherub”—“Pretty Pet”—I go to Bordeaux

CHAPTER III FRANCE Bordeaux—I dance at a café chantant—I fight with Pretty Pet and leave him—I am taken on as a professional dancer—The Apache—I go to Paris—The Apache gang—I fight with Hortense—“Tiger-Woman”—I fight with The Strangler—The methods of the gang—The branding—The gang is dispersed—I return to England

CHAPTER IV GETTING MARRIED The Café Royal again—Some notable people—The Crabtree Club—Bunny—I get engaged—I go to Cornwall to be improved—The Rectory Life in the country—Practical jokes—I escape to London—Arthur—Engaged again—A surprise marriage

CHAPTER V DRUGS AND DIVORCE My honeymoon—Cocaine—Scotland—A curious household in London—The outbreak of war—Bunny joins the army—I am left alone in London—Chinese hair-nets—Divorce—A chivalrous Australian—A thrashing—Back to the Café again—I sit to Epstein for “The Savage.”

CHAPTER VI THE MYSTIC Raoul—The Princess Amen Ra—Marriage again—The spirit photograph—My walk to “The Trout”—An apparition—I meet the Mystic—The White Magician—The Mystic at the Harlequin—I visit the Mystic’s house—Raoul decides to go to Sicily

CHAPTER VII THE ABBEY We embark for Sicily—Discomforts of the journey—Cefalu—We arrive at the Abbey—Life in the Abbey—The razors—Jack the Ripper’s ties—“We shall sacrifice Sister Sybiline at eight o’clock to-night”—Pentagram—Raoul’s ill-health—The sacrifice of the cat—The death of Raoul—Raoul’s burial—I return to England

CHAPTER VIII I GO TO AMERICA Jacob Kramer—A fox-hunting painter—A mad visit to Yorkshire—Poverty—I appear in the papers—Princes Waletka—New York—Broadway—An Indian Reservation—Montreal—I part with Waleth—I return home—I meet Carol—Marriage again—Life in the country—My shop—The Rookery—Carol’s illness—I run away

CONCLUSION

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

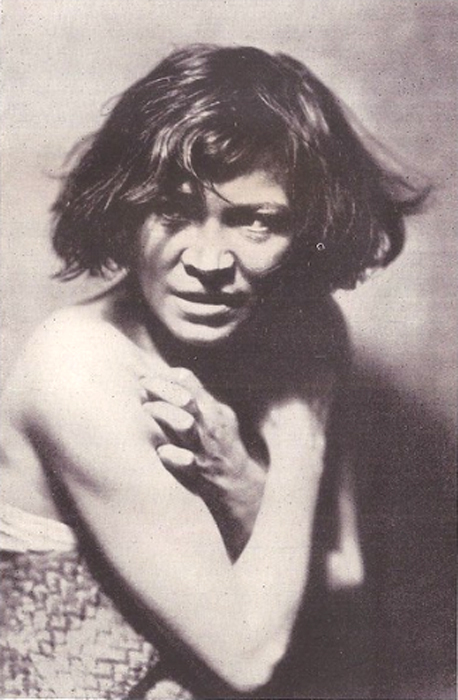

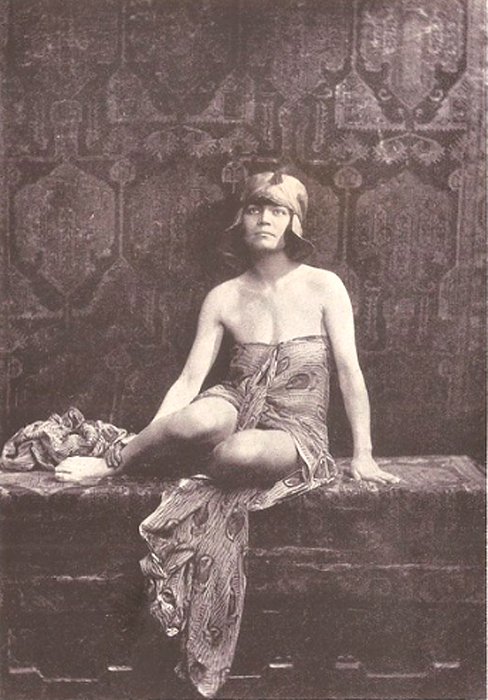

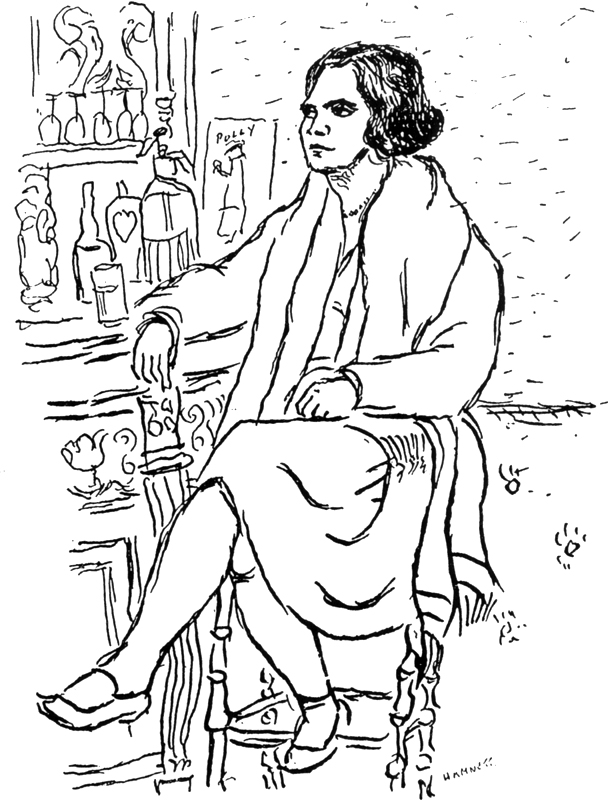

Betty May, “The Tiger Woman” Frontispiece Betty May The Old Café Royal. By Adrian Allinson Betty May Betty May Betty May. By B. N. Satterthwaite “The Sphinx.” By Jacob Kramer Betty May Betty May at the FitzRoy Tavern. By Nina Hamnett Betty May. By Gerald Reitlinger Betty May. By Michael Sevier

INTRODUCTION

I Suppose that a good many of the people who read this book (if any do!) will have heard of me already. Some of them will actually know me and remember the things and the people I am going to speak of. They will recognize several of the individuals who are called only by their Christian names, or who are only described by their appearance or most marked characteristics. For these it may be interesting to recall the old times of before and during the war—now that everything is so altered—and the adventures that we used to have in those days. But there will be a great many people who will never have heard of me at all, and for them I want to explain a little of myself if possible, before I begin. I want this to be a frank history of my life. By this I mean that I want people to realize what I am really like. A lot of the stories I am going to tell are, I suppose, rather unpleasant home-truths about myself, but I am not ashamed of them. They are all part of me, and when you have read my story perhaps you will understand in some way how my character has been formed.

When I read through this book the thing that struck me most was what an exciting life I have had up to the present (you see I am not even middle-aged yet). But in spite of this it has not really felt so exciting while it has all been going on. Of course bits of it have been thrilling, I admit. But then for long periods nothing seemed to happen to speak of, and I had no money or was terribly bored or something like that, and things did not seem bright at all. I suppose everybody’s life really feels much like that however exciting it is, and I should be grateful for the experiences that I have had. I have only written down events that I thought would interest everybody because I thought otherwise no one would want to read the book, and one thing I should like to make clear is that the things which are likely to interest everybody are not always the things that have interested me most. I have had all sorts of experiences which mean a lot to me but would not interest anyone else to hear about. I suppose every woman carries in her heart memories that mean more to her than all sorts of exciting stories she might be able to tell. It is certainly so with me, and if there are people who know me and read my story and wonder about why this person or that episode has not been mentioned, it is possible that they may find an explanation in what I have said above. On the other hand, it may just be I that have forgotten, for it has not always been easy to remember every incident in one’s life.

First of all you must realize that I have never tried to be ordinary and to fit in with other people. I have not cared what the world thought about me, and as a result I am afraid what it thought has often not been very kind. I have had love affairs, some of which you will hear about and some of which you will not hear about. I have often lived only for pleasure and excitement, but you will see that I came to it by unexpected ways. Fate seems to have led me there, for I have lived in a world which I was certainly not born to. In fact nothing could have been further from it than the surroundings in which I was brought up. And now having said this, I hope everyone will feel in a sympathetic mood to hear about me. If they do not they had better put my book down, for I am going to tell my story in the same sort of way that I have lived my life.

CHAPTER I

CHILDHOOD

Myself—Earliest memories—My coster grandmother—A suicide—I am sent to live with my father—My father’s bad character—His arrest by my grandfather—Life on a barge—I dance for some sailors—I go to Somerset—The schoolmaster—I am sent to London—The beginning of adventures.

Tidal Basin, where I was born, and spent most of the single-figure years of my life, is as everyone knows, one of the poorest and most squalid districts in London. At the time when I can first remember, my father had already left us, convinced, I suppose, that having begotten four children, nothing further could reasonably be expected of a man. And even the law failed to extract from him any contribution towards our support, although I believe he used to be sent to prison at intervals for refusing to pay anything towards his family’s upkeep.

We lived in one room, with a scullery attached, containing a round white copper: The only other furniture consisted of a table, one or two very broken-down cane-bottomed chairs, and a carpet chair in which my mother used to rest of an evening, with a folded ironing-blanket for a cushion. We did not possess a bed, and at night used to sleep on bundles of rags in the various corners of the room.

My mother was half French, and at this time still very good-looking. Not more than five feet in height—I am no taller—she had a rich olive complexion and beautiful dark eyes set very wide apart, which I have also inherited. Her nose, however, was better than mine, being a delicate aquiline, whereas mine is, to be honest, rather a snub. Her life must have been a hard one. She had four children to bring up on a total income of ten shillings a week. And to earn this meagre sum she had to work twelve hours a day at a chocolate factory. It would have been excusable if she had neglected us. The amount of work she had to do in the course of the day was simply awful, for I am afraid that as a family we needed a good deal of looking after. I suppose we inherited this from our father. But so long as my mother’s strength held out she never surrendered. Although ten shillings a week was not enough to keep us warm and well fed, she at least persevered in keeping us and our home clean. Only the black-beetles escaped all her efforts. I shall never forget the sensation of crushing them under my bare feet. They used to give a sort of scrunch.

Sometimes, but not often, she was able to bring us back some chocolate from the factory. Oh! the delight of that chocolate! It was almost worth being half-starved to enjoy it as we did.

I have only one more recollection of these very early days, and that is of a tall, bearded man who visited us one winter evening. Ordinarily we should have retired for the night by the time he arrived, but apparently my mother was expecting him, for she kept the lamp burning. I imagine he was a seaman as he wore small gold rings in his ears. He stayed for a long time, and my mother seemed to enjoy his company. Before he went he took me on his knee and played with me.

From this time onwards he always used to come and see us when his ship was in port, and we got quite used to him. I was always his favourite and he never played with any of the others. His nickname for me was “The little flea,” on account, I suppose, of my small size and great quickness of body and mind.

When we were a little older my brother and I used to be sent round to my grandmother’s house every Monday morning to fetch the vegetables for our weekly pot of soup. This was rather an event in our lives. Not only was it the most important meal of the week but also one never quite knew what sort of a mood my grandmother might be in. Anything might happen. My grandmother was a remarkable woman, a real coster. Her hair, which she always wore heavily greased and drawn straight back in a tight little knot at the back of her head, was as white as her invariably clean apron. Her face was equally white, making her eyes appear very conspicuous. My brother called her “two holes burnt in a blanket,” and infuriated her by calling this after her in the street and running away before she could catch him. She was a really great character and people were very afraid of her.

I often used to walk with her to the market. As soon as we got there we used to go into a pub, where she bought me the same drink as she was having herself—usually either gin or porter. Then came the actual marketing, after which we had another drink and returned home, my grandmother carrying all her purchases—folded up in her apron.

It was at my grandmother’s house that I first came in contact with death. She lived on the first floor. Below her was a household consisting of a man, his wife, and his sister-in-law. One day my grandmother told me to go down and borrow some milk from them. I knocked at the door. There was no reply. I cautiously opened the door and, looking in, I saw the wife suspended by a stocking from a hook on the door leading into the bedroom. Her face was purple and her eyes bulged like a fish’s. It was rather an awful sight, and in spite of things I have seen since then it has always remained firmly fixed in my memory. I can see the body hanging there as if I had only gone into the house and seen it a few days ago. It is extraordinarily vivid to me.

“Can you lend grandma a bottle of milk?” I asked, not knowing how else to attract her attention.

When she made no reply I was rather frightened, and thinking she must be ill, ran upstairs to tell my grandmother. Her reception of the news disappointed me very much. Instead of being treated with the respect due to what I was, beginning to think must be important news, I was sent packing, and told not to say anything about what I had seen to anybody. Of course I told everybody I met, but as none of them could give me any satisfactory explanation I decided to ask my mother as soon as she came home. To my intense disappointment she behaved in the same evasive way as my grandmother had done. I was not, however, even at that age, so easily put off, and I soon found out the facts of the story, which were as follows. The wife was expecting a child and had moved into the front room for the period of her confinement. The husband, deprived of her, turned to his sister-in-law, who did not refuse him. By reason of the limited accommodation at their disposal it was not long before the wife’s suspicions were aroused, and one day not long before her delivery was expected, hearing what she took to be suspicious sounds in the adjoining room, she arose, investigated, and discovered them. So great, apparently, was the shock of realizing this double infidelity that, unable any longer to endure such a world, she decided to leave it rather than bring another life into it.

Although it did not always end in suicide, this sort of episode was fairly common I discovered as I began to grow up. I think it gives you some sort of idea of the squalor and misery in which I was brought up, and for this reason I look upon it as important.

My grandmother, I have said, was a real coster woman, and the strain of coster blood I inherit from her has had a big effect in moulding my personality. I am a true coster in my flamboyance and my love of colour, in my violence of feeling and its immediate response in speech and action. Even now I am often caught with a sudden longing regret for the streets of Limehouse as I knew them, for the girls with their gaudy shawls and heads of ostrich feathers like clouds in a wind, and the men in their caps, silk neckerchiefs and bright yellow pointed boots in which they took such pride. I adored the swagger and the showiness of it all.

My brother and I used to explore together the remotest parts of Greenwich and Chinatown, often returning very late at night, much to the irritation of my mother, who wanted to rest after her day’s work. She often scolded us, but we didn’t care, and returned probably even later the following night. There were extraordinary things to be seen in the narrow streets by the river. I suppose it was really a suitable early training for me. It taught me that you could never know what was going to happen next.

I was, I must admit, a good deal frightened of my brother, and my rebellion was partly due to his threats, which he was never afraid to carry out. If ever I showed any sign of refusing to do what he wanted he would pinch me till I gave in, or push me into a canal. On one occasion, however, I had my revenge on him. It was a hot day and we had walked down to one of those Greenwich streets, where there are many little tributaries of the Thames. He was hot and tired, and, thinking it would be pleasant, took off his boots (the only pair in the family) and waded into the water. As soon as he was out of reach I picked up the boots and threw them out into the middle of the stream. They floated a short way and then sank.

My mother was furious when he returned without the boots, and asked him what he had done with them. He naturally told her that I had thrown them into the river. I, however, said that he had thrown them at me standing on the bank and missed. Despite his furious denial of this, she believed me. I was always her favourite. Then she gave him a halfpenny and sent him out to buy a cane. He, knowing the use to which it would be put, spent the halfpenny on sweets and stayed out till after midnight. I had never seen my mother so angry. Our escapades must have been getting on her nerves. As soon as he came in (without the cane) she seized him by the collar and beat him with the rolling pin till he yelled. It was one of the moments of my life.

But delighted though I was personally with my success, I could not help seeing that the loss of the boots had just tipped the balance so far as my mother was concerned. Her powers of resistance were finished. It was therefore no surprise when one morning a few days later my brother and I were sent to my father with a note explaining that henceforward we should have to live with him.

This was the first sight I had of my father. He was lying on a filthy couch half covered with a rug. As we came in he propped himself surlily on one elbow. He was wearing a collarless grey shirt and leather braces, I remember. His face was almost fleshless, and the working of his loose-lipped mouth had creased the tightly drawn skin from his temples to his jawbone. His eyes were light blue, rather crazy and dangerous looking, and very bloodshot. His right eyebrow was almost obliterated by a scar which kept the eye beneath it unnaturally open. He looked absolutely devilish. I was terrified of him and dreaded what our life was going to be like here. I wished I had behaved a little better to my mother, who then might have kept us with her. I now realized how silly I had been.

At the foot of the couch sat a huge dark Jewess, whose one-time beauty was obvious. She was now enormously fat and shiny, though she was still a fine looking woman. She evidently resented our intrusion, and as soon as she had learnt who we were she advised my father to “send the little bastards to the workhouse.”

His retort was to get up from the couch and floor her with a fierce blow in the stomach. Then leaving her to recover, he turned to us and said: “So your mother has sent you to live with me?”

We told him this was so, and it was settled.

The atmosphere of the house was very different from that of our previous home. We were never “allowed” in any other part of the house than the room in which we first saw our father. Day and night we heard people going up and down stairs on some mysterious business which we rightly imagined was being intentionally kept from us. Later I discovered that the place was a brothel run by the Jewess Sarah, on the proceeds of which my father lived and drank in idleness.

The actual conditions of life were much the same here. We had if anything less to eat, and we slept, or tried to sleep, as before on bundles of rags in the corners of the room. In winter my brother and I used to huddle together for warmth. Dreadful was the nipping of hungry bugs, and the cough of an unknown consumptive who always slept in the opposite corner to me. In the summer the stench and stuffiness were such that, although it was strictly forbidden, I used to sneak out and sleep on the stairs, where it was cooler. It was pretty hard sleeping there and you were quite often disturbed by people coming in late and falling over you, but the breath of fresh air which you got there made it worth while facing the discomforts. The first time my father found me there he gave me a long lecture—I honestly believe he felt he was doing something towards redeeming a misspent life by keeping his children from knowledge of evil—and threatened, if he caught me there again, to whip me with an engineer’s steel foot-rule that he was carrying. I disregarded his threat, thinking that bully though he was he would not whip me. The next time he caught me, however, he was in a less sentimental stage of drunkenness and carried out his threat.

He was naturally cruel, and when drunk, as he usually was, he became a fiend. One of his favourite amusements was to set our two dogs, Nigger and Rags, to fight one another. Or if he saw a cat in the street he liked to pick it up by its tail and crash out its brains against a wall. The one virtue he both possessed and respected was bravery. He feared no man in Limehouse, and in certain moods he would go out into the street and shout, “Come out, you ————s and fight.” Only one man ever answered the challenge, and he had to be taken to the hospital in an ambulance. He trained my brother to be like himself. When only eight years old he was beaten in a fight by a much larger gipsy boy and came home crying to my father, who cursed him for a bloody snivelling little coward, and told him that if he did not go back and fight the gipsy boy till he beat him he would get a far worse hiding at home. My brother went back and thrashed the gipsy boy. When he returned with the news, any father simply shook him by the hand.

By trade my father was a mechanic, but since he had come to live with Sarah he had not found it necessary to do any work. He would just sit about all day drinking and smoking, and if possible picking quarrels with anyone he came across and who was prepared to have a row with him. Previously he had been employed as a fitter in a gas works, and he was so good and quick a workman that he had retained his job in spite of his periodic disappearances. Any kind of regularity, however, he hated. His parents, and my grand-parents therefore, were a cook and a policeman, who had several times tried to put him in the position of making a settled livelihood. Of the fact that his father was a policeman (he became an inspector eventually) I shall tell you more in a moment. It was a most unfortunate thing for my father. Once at his request they had bought him a fried fish business, for which they paid fifty pounds. He ran it for two days, and on the third sold it, stock and all, for a pound. Another time they bought him a fruit barrow for five pounds, and he sold it for half a crown. I am rather like him in money matters.

My removal from Limehouse was very sudden and rather a shock. I was awakened in the middle of the night by the sound of someone banging on the door. It was pitch dark. I huddled into my corner, covered myself with the rags I had been lying on, and kept perfectly still, hoping I should not be noticed. Then I heard a match being struck and a voice inquiring for my father. I was sweating with terror. Deliberate footsteps approached the corner where my brother was sleeping, and the voice said, “Do you know where father is, sonny?”

“No,” came my brother’s piping reply. “Maybe he’s upstairs.”

The footsteps went away and the door was shut. But the lamp was left burning, so I knew that the business, whatever it was, was not finished yet.

“Who was he?” I whispered to my brother.

“A copper,” he whispered back.

“What does he want Dad for?”

“I don’t know.”

We waited for a few minutes. Nothing happened, though we heard the policeman’s steps. Then there was a bit of a scuffle and we heard someone swearing at the top of their voice.

The door opened again and the copper re entered, leading my father, protesting violently, by the arm. My father was wearing handcuffs. It was only then that I saw who the policeman was. It was my grandfather, who was an inspector of police. He had warned my father over and over again that this would happen unless he turned over a new leaf and now it had come to this. He had been sent to arrest him. It was an extraordinary thing to happen.

My grandfather told us to get up and dress, which was unnecessary, as we always slept in our clothes. He was very gentle with us, and said we should be quite all right, but we must come along with him. He then took me by the hand, gripping my father’s arm with his other, and led us out into the street. We made a lot of noise going down stairs. Our foot-steps sounded very loud. My grandfather’s firm and heavy, my father’s shuffling and reluctant, though he did not actually try to get away, my brother’s quicker, my own tiny ones pattering and timid. They must have sounded very funny.

At last we came to a building with a blue lamp over the door, into which we were told to go. Inside we were separated, and I was taken to a cell with quite a comfortable bed in it, and locked up for the night. I soon went to sleep.

Next morning they brought me a cup of tea and some bread and margarine—the nicest food I had ever tasted. At ten o’clock we were brought before the magistrate. I did not understand what the discussion was about, but one of the incidents of the trial was that my grandmother, who was the only person my father was at all afraid of, was so angry with him for bringing public disgrace on the family that she rushed up to him and hit him hard over the head with the thick rolled umbrella she always carried. There was a frightful scene I remember. I heard the magistrate say, “And the little girl can go to her grandmother’s.”

This was my other grandmother—my father’s mother. I was handed over to her as soon as the case ended. But instead of keeping me she sent me to an aunt and her husband, with whom I lived on a barge for the next few years.

My father, I heard later, was sentenced to two years’ imprisonment, after which he and his twin brother went out to Canada, and joined the mounted police, where they gained credit for their bravery. When the war broke out my father joined the first Canadian contingent that came over here. He never got to the front, however, where he would probably have done well, but catching a chill while in training on Salisbury Plain he died of double pneumonia.

My life now changed completely. It became much duller for a bit, but it was also a good deal more comfortable. I was properly fed and looked after. However, I am not sure that I was really grateful for the change.

All day long my uncle used to sit grasping the tiller in one hand and the bowl of his short stemmed clay pipe in the other, with his eyes fixed in a very firm stare on some point a few feet above the beautifully carved green and yellow figurehead, as if he were slowly considering whether it was worth while recollecting all his adventures—though his meditations were more probably concerned with the question of dinner. The stream brushed the sides of the boat as slowly as can be imagined, and the landscape always seemed to be the same. Sometimes I wondered whether I should ever get away from these rivers and canals and see the life that must be going on in the world on shore.

I was a little brown-faced marmoset, dressed in a starched white frock, and the only quick thing in this very slow world. I skipped about, getting in my aunt’s way in the tiny kitchen, or else dirtied my clothes and myself by playing among the cargo, and generally I was getting into trouble in some way or another.

My aunt and uncle were, I suppose, very kind to me. They washed me a good deal, forbade me to use certain words, brushed my hair far longer than I thought necessary, insisted on me cleaning my teeth twice a day, and taught me the Lord’s Prayer.

“The poor child,” I once heard my aunt say, “has had no proper upbringing. She’s a regular little savage.” My nature, however, was then as now not very tractable to “improvement.” I have never wanted to be different from what I am, and have jealously repelled or fled from any influence that seemed likely to alter my personality. I chafed under the restraints and monotony of life on the barge, and was for a time sulky and miserable. My aunt and uncle took no notice of me.

This feeling of neglect reached a climax one evening when we had moored for the night after unloading our cargo at a wharf near Chelsea. I had been ashore—a rare pleasure—and had spent the few pence I possessed on a scarlet handkerchief, which I tied round my head, and which I felt sure looked very becoming. On returning to the barge I ran up to my aunt to show it to her, saying, “Don’t you think it’s pretty?” She looked up from her work crossly and replied, “What? That thing on your head? Don’t be so silly.” I stamped out of the cabin in tears. Nobody cared a bit about me. I didn’t matter. I would run away and find some people who did, which would be easy. Of that I had no doubt. I knew I was not destined to live and die unnoticed. I knew even then that my life was not to be an ordinary one.

And so I went to sleep, bitter and miserable. However, as it happened, I was on the point of discovering that everybody did not think like my aunt and uncle. I was going for the first time to take a real line of my own.

The next morning I was surprised, on looking out of the minute window, to see that a big ship had drawn up alongside us during the night. I dressed, put on my despised headdress, and went out to look at it. As soon as I emerged a bunch of sailors on the deck called down to me, “Hullo, kid.” Then some impulse or other urged me to dance for them. I had never danced before, but it came quite easily to me. They were delighted, and threw me pennies. I danced more and more, and even sang, and they threw down more pennies, and at last a sixpence or two. They were enthusiastic about my performance. I was delighted. At last someone seemed to understand and appreciate me. Perhaps life was not going to be so bad after all.

After this I would always dance whenever we were near a ship, which happened quite fairly often, and, as all sailors seemed to like watching me dance, soon I became quite well known up and down the river.

Some time after this—I really cannot remember exactly how old I was when various things happened—it was decided that a start ought to be made with my education. I was sent to another aunt, who had a farm in Somerset, and for the next few years I attended the village school. I do not think I managed to learn very much there. In fact lessons rather bored me, but even here I got to know more about life, and it was from here that I was to start off on my real career.

This country existence was as strange to me as I myself—no doubt was to the people I found myself among. For a week or so I found it lovely. To be awakened by the crowing of cocks, to open my eyes upon fruit trees gently swaying against a blue sky, to dress, eat a large breakfast (bits of straw still sticking to the egg shells) and then proceed down the path which divided the oats from the barley, and across the wide village green where the ducks quacked round my ankles, to the village school standing next to the church. I entered joyously into the reality of what I now know was a childish dream. I played my part as happily, as wholly, as singly and as passionately as only those can who half know they are playing a part. I dangled my sun bonnet by its strings. I stuck poppies and daisies in my hair. I was plump and brown and healthy. Two boys from the grammar school fell in love with me.

I always went about attended by a contingent of grammar-school boys. They were for the most part older than I, but they had not had my experience. I was the acknowledged leader. What games we had! What scrapes I led them into!—always escaping the blame myself on the ground “of being only a little girl. I taught them to get drunk on cider, and when they became accustomed to that I stole my aunt’s burgundy and filled the bottle up with water. These things may sound rather silly, but I think they show the direction which I was going to take, and for this reason they rather amuse me to remember and to tell you about.

One of our most amusing exploits was my revenge on a priggish little girl called Edith, the chemist’s daughter, who told tales about me to the school mistress. Her parents were very proud of her, and every Sunday used to dress her up in the most elaborate frocks, with huge sashes and hair ribbons to match. I thought of something. I went out and bought a packet of drummer dyes which I dissolved in a large rainwater butt. Then I detailed some of my cavaliers to isolate and capture the little beribboned horror, whom we immersed, finery and all, in the mixture I had prepared. We left her screaming and clinging to the edge of the butt, and withdrew to enjoy her struggles. At length she had to give up calling for help that showed no signs of being forthcoming, and to climb out by her own efforts, derisively encouraged by her tormentors. Her appearance when she did eventually emerge, an awful, bedraggled mess, weeping indigo tears, and spluttering threats of the penalties she would see were inflicted on us, was a sight on which any inhabitant of this sad world could close his eyes with a contented sigh.

The years passed in this way, and without knowing it I began to grow up. I suppose in a way this time in the country was a happy one. Nothing much happened, but then I did not expect anything much to happen. It was a sort of rest to prepare me for the sort of thing that was to come. One of the masters of the grammar-school had meanwhile been taking an interest in me. We met for the first time outside the school gate, where I was waiting for my friends to come out. He was a youngish man with a clean-shaven florid face and a large letter-box of a mouth, through which he uttered slightly facetious remarks in a clipped and, to me, unfamiliar accent. He always wore grey flannel trousers, a tight fitting cloth cap, and a sports coat with sleeves that looked about an inch and a half too short. But although his manner was outwardly rather domineering and patronizing, I felt that he was sad. He might have been ambitious in his boyhood, or perhaps he might have been in love, though this seemed impossible to me. But whatever he may have longed for, I felt sorry for him. With me he seemed to be able to recover for the moment some of his lost dreams.

For my part I learned a great deal from him. He was one of the first cultured men I had ever met, and I naturally love culture. He used to take me for long walks on Sundays, during which with infinite patience he would try to reveal to me spiritual pleasures of which I had never before had an inkling. For this odd man had an enthusiasm for Keats, and knew nearly all his poems by heart. It must have been pleasant for him to find a sympathetic, if not well-read, listener.

For a long time we used to go about together. The understanding between us grew more and more strong. I can hardly say, in the light of what I have learnt since, that we were in love. At least perhaps he was. Certainly I was fond of him. And thus things went on until we were more intimate than my aunt and the rest of the village gossips thought proper. I see now looking back on it that it was a relationship that could not last. I do not think either of us was altogether to blame. After all, he was lonely. There was no one in the neighbourhood he could meet on equal terms or whom he could talk to about the things he loved. I myself at this time had not been very happy with the people I knew. I longed for a bigger life, and I felt that such a life did really exist somewhere if only I could get to it. By his conversation this man had shown me something of a world I had hardly dreamed of. But none of this was considered to be of any account by everyone else. There was a great deal of fuse, and it was made clear to me that unless the friendship came to an end it would be the schoolmaster who would be made to suffer. I did not take all this lying down, but I could not do anything to prevent it. The result was that after a rather tearful scene with my aunt I was packed off with a few pounds to make a start in life somewhere else. And so in sorrow and not a little fear I found myself one day in the train bound once more for London.

What did I think of on that journey? Did I reflect—after I had, produced my ticket—that the departing landscape (I forget whether it was summer or winter, or harvest or seed-time) was perhaps symbolic of lost innocence? Did I realize that I had finally cast off the comfortable shackles of childhood, and was being whirled, as the novelists say, at the rate of sixty miles an hour—why always sixty miles an hour?—towards London, into whose midst I should so soon be helplessly sucked? I wish I could remember the answers to these questions, but I have really forgotten, and so if I want my readers to believe in the truth of these memoirs I will not try to imagine these things but will just admit this fact to them. Certainly I suppose I ought to have been thinking on these lines, and those who happen to read this book may take it that I actually did so—which is, after all, as likely as not. If they so desire, let them be assured, too, that the ticket collector was a fat man with a squint, who had a wife and three children at home, and advised me where to go when I arrived in London.

He may indeed have done so for all I can remember, since it is certain that I should not have taken his advice. In a way I was rather excited to be on my own at last. I now knew that I was in for some adventure. I did not know where I should find it, but I felt pretty sure that it would appear soon. I went, as it happens, straight to the Commercial Road, a district I had been familiar with before I went to the country, where I immediately bought myself some “grown up” clothes, a skirt that would have touched the ankles of the person it was designed for—worn by me it not only threatened to trip me up at every step, but was in serious danger of slipping off altogether—and a monstrous hat, trimmed rather like an old-fashioned ship under full sail, which the secondhand dealer assured me was exactly how hats were being worn at Ascot and Goodwood that year.

Thus arrayed, I stumbled out into the street, clutching anxiously at the folds of my absurd skirt with one hand, and with the other continually feeling it for the small sum of money with which I had to make my start in life without further help from others, to assure myself that it was still there—a comical sight. For a long time I wandered about, not knowing what to do or how to get a room, until I encountered ~a young Jew, who took me into a pub and gave me a gin, the first I had had since going to the market with my grandmother, many years before. In the pub a kindly woman asked me how old I was, and offered to take me home with her to sleep. I gladly availed myself of her compassion, but could not bring myself to tell even her the reason why I had come to London.

This was a real bit of luck, of course. Goodness knows what would have happened to me if this woman had not looked after me at that moment. As it was, although I was not with her for long, I got used to being in London and became more full of confidence.

A short time later my protectress was compelled for business reasons to leave me in a public house with some friends, who promised to see me home. A well-dressed man, however, came in shortly after she had left, who showed a good deal of interest in me and offered to take me to the West End. I am never able to resist adventure, and against the advice of my friends I consented to go with him.

Their advice was justified by his conduct as soon as he got me alone in a taxi. I was terrified. I resisted him in all the ways I could think of. I fought and scratched, and I did not scruple to bite. Failing in the direct physical attack, he fell back upon persuasion—a stage in the winning of a woman which I gather he had in his previous experience found it possible to do without. He pointed out all the advantages, the clothes, the dinners, the good times, I should gain from an association with himself. But I was not moved. He sketched the squalor and poverty in which he had found me, and from which he intended to remove me, but I was not grateful. He then abused me for a lousy little slut, who ought to be left to wallow in my own filth: I replied by asking him why he would not permit me to return to it. This infuriated him. He stormed and threatened, and lastly, as a climax, declared that he loved me.

As I have indicated, and as the reader will easily believe, I was not at this time in a mood to enjoy love making. Fear can turn every prospect and glamour of romance to mud, and I was frightened. Consequently his abasement won no more from me than his assaults or his bribes or his abuse or his threats had done. I hated the sight of him and told him so. I wondered why men would not leave one alone. They were all right at first when they offered to show one life, and then at once they became a nuisance.

This, or something like it, must, I think, have been the reasoning that led him to the course of action I am about to describe. I suppose he thought that whatever he was going to get out of me would only be got after a great deal of trouble, and quite likely not at all. He probably did not like people like that, and so that was why he acted as he did.

The taxi stopped in what I found out later to be Leicester Square. My companion assisted me to get out and led me by the arm to the door of a club—now extinct—situated close to where the Café Anglaia now stands, on the east side of the Square.

“Are you sure you wouldn’t like to come in?” he asked, while we waited for the attendant to appear in answer to our summons.

“I suppose I’ll have to,” I said more sulkily than ever.

“Are you sure you couldn’t love me?”

Before I could answer, the fanlight was illuminated and the door opened, revealing a flight of uncarpeted stairs, up which floated sounds of music, dancing, chatter, and the chinking of glasses. I describe the scene in detail, because the next moment, without any warning, he pushed me down the stairs and went away, banging the door behind him.

Betty May

CHAPTER II

THE CAFÉ ROYAL

My first night club—Rosie’s wig—A Cambridge undergraduate—The Endell Street Club—I am taken to the Café Royal—Epstein—Augustus John—Horace Cole—Epstein speaks to me—The Cave of the Golden Calf—Madame Strindberg—“The Cherub”—“Pretty Pet”—I go to Bordeaux.

The episode I have just related, or to be more accurate am in the middle of relating, is a good starting-point for the next phase of my story. The door through which I had been thrown so violently, shut with a loud bang before I came to rest at the bottom of the stairs, and you can imagine my consternation when I looked upwards to find my pursuer had disappeared.

Awakened by that bang to my senses I looked up and around and surveyed a new world containing no familiar figure—not even his who had been responsible for flinging me there. Next I proceeded to investigate in greater detail the people and the surroundings among which I had been marooned.

This was my first sight of a life that I was afterwards to know so well. In the corner a band was playing, and on a shiny floor couples were dancing. The place was simply packed with people, and the atmosphere was very thick with smoke. Everybody seemed to be talking at once. I felt quite dazed and rather frightened, and did not in the least know what to do with myself. I was of course in a night club, but I had hardly heard of such a thing in those days and I certainly never expected to find myself in one. Anyway I had not thought beforehand that I should suddenly be literally thrown head-first into one.

Entering the room at the end of a dance I saw only one vacant chair, on which, after politely obtaining the permission of the man at whose table it was placed, I sat down. My intrusion, or more probably the interest the man showed in me, aroused the resentment of his female companion. She began by taking advantage of my ignorance to try to make me appear ridiculous, but I was not even then to be made fun of so easily. My wits were far sharper than hers, and I soon discomforted her. Irritated by her failure, she became insulting. My nostrils dilated, as they do when I am angry, but still she dared to jeer at me. This went on for some time. The man was quite nice and talked to me kindly, but she kept on interrupting and being as rude to me as she could. I tried to make up my mind what to do. At length she got up and danced with the man, who would no doubt have preferred to remain at the table, and as they passed by where I was sitting she looked backwards at me over her shoulder. “She’s a pretty little thing, but it’s a pity she has false teeth!”

She said that I—I—had false teeth! This was more than I could endure. I jumped up and slapped her as hard as I could on the face. Shocked waiters immediately bundled us upstairs into the street, fighting all the time. I meant to make her pay dearly for that insult. False teeth indeed! I would strangle her for it. No, on second thoughts I would catch her by the hair and smash her face so that she would never attract another man—that would be a better revenge I decided, and I had begun to put this plan into execution. I plunged my fingers into her hair and pulled hard, but the result was not what I expected. I found myself lying in the gutter, and clutched in my right hand—I could hardly believe my eyes—was a chestnut wig.

All my anger against her died down on the instant as I saw her standing there, hairless as a worm. Seldom have I seen a funnier sight, and never a woman so thoroughly humiliated. I must say that after this happened she behaved very well. Instead of being angry, she asked for her wig back and crammed it on to her head, telling me to say nothing about it and asking me to go back to the club with her. After this she was very kind.

When I had done laughing, I returned her the wig, and Rosie and I, for that was her name, went back to the club quite good friends.

Soon after this incident she married a young man and went out with him to New Zealand, where they bought a farm out of her savings, and are, I believe, living happily to this day. But I often wonder if he has yet discovered that she wears a wig.

This was really my introduction to the world that I was going to live in for the future, and in many ways I suppose it showed me the sort of thing I was in for. Anyway it turned out that the incident I have just told you about was all for the best.

From this time on I began to find my feet. Rosie helped me to find a room, and I found that after paying for it I could still afford to buy myself some clothes. In the choice of these I was able to show for the first time the flamboyant taste in colour that I inherit from my coster ancestry. I could only afford one outfit, but every item of it was of a different colour. Neither red nor green nor blue nor yellow nor purple was forgotten, for I loved them all equally, and if I was not rich enough to wear them separately, rather than be parted from any one of them, I would wear them, like Joseph in the Bible, all at once! Colours to me are like children to a loving mother. Each is my favourite, yet I can never bring myself to deny the others by preferring one.

It is very irritating to me that I who always know my own mind should be to this day unable to come to a decision upon this matter. It is too bad. But I always feel that I have got my own back when I wear all colours at once. Few people, you will find, if you read this book to the end, can boast of having come off best in competition with Betty May!

Dressed then in the brilliant colours that are my right and heritage, my personality burst suddenly forth in its full peculiarity. From this moment I felt I was grown up and after the experiences I had had I could now start life. As I looked at myself in the mirror after my latest purchases, in my new finery I felt I was now ready to descend upon the expectant world.

The person, however, who was really responsible for discovering me and taking me to the scenes of my future life was a nice-looking boy from Cambridge, whom I shall refer to as Gerald. I was standing one night outside the Holborn Empire watching the people and feeling very lonely when he came up and spoke to me.

“Would you like to go in” he asked.

“Yes,” I said, “I’d love to.”

So he took me in to see the show and afterwards we made great friends. As I found him kind and well off, we saw a lot of each other and often went out together. He was charming; and I used to amuse him a great deal by both my knowledge and ignorance of the world which always seemed to him such an extraordinary mixture. I began to get the fever of night life in my blood. And wherever we went people wondered who was the girl with long plaits who dressed so oddly.

Among other places, we frequented the Endell Street Club, a favourite resort of journalists before the war. It was here that I met Jack C——, an American over here on a visit, who was to take me for the first time to the Café Royal. He was greatly intrigued with me at first sight, and I liked his appearance. It turned out that he was a great help to me. I was, I remember, very depressed after seeing Gerald off on the way back to Cambridge, and could not endure the prospect of going back to the place where he had arranged for me to be looked after while he was away. He had made me promise not to go out to night clubs alone, but I didn’t care. I dislike solitude, and if he had understood me he would not have exacted such a promise.

Reasoning thus, I went straight from the terminus to the Endell Street Club. Jack was there and asked me to meet him at the Café Royal the following night.

I remember there was a very lovely German woman who used to be at the Endell Street Club a great deal. She was always beautifully dressed and covered with sparkling jewels. She always used to make me, with my two long plaits, feel very young and unimportant. (By the way, I used to put these plaits up under my hat before going into the Club, but they usually came down in the course of the evening.) One evening I was standing beside this beautiful German, and I asked her straight out how she came by all her fine clothes.

“Would you like some?” she said.

She then explained to me that she earned her living by blackmail. She gave me a complete description of how she worked. She suggested that I should join her, saying that my appearance and childlike looks would be very useful in her profession. I was terribly shocked and upset by all this. In spite of what I had seen in the way of vice and crime this seemed different somehow. Anyhow, I was very rude to her and we never spoke again.

The old Café Royal was a very different sort of place from the new one. It was, to begin with, a real café. There was sawdust all over the floor and none except marble topped tables. The gilded decorations were as gaudy and as bright as possible. The drinks were quite cheap. I cannot describe them more accurately than that, and must rely on the memories of those of my readers who, like me, knew and loved the Café as it then was. I find now that I am always meeting people who never knew the Café as it was in the old days. They always talk of it and think of it as the rather grand place it is to day.

I had never seen anything like it. The lights, the mirrors, the red plush seats, the eccentrically dressed people, the coffee served in glasses, the pale cloudy absinthe. I was ravished by all these and felt as if I had strayed by accident into some miraculous Arabian palace.

Though Jack, who knew the Café well, could not understand my enthusiasm, he agreed readily to take me there again, and partly out of gratitude and partly to make sure that he kept his promise, I always went about with him while Gerald was at Cambridge.

No duck ever took to water, no man to drink, as I to the Café Royal. The colour and the glare, the gaiety and the chatter appealed to something fundamental in my nature. I took to going there nearly every day, even if Jack could not come with me. I used to sit at a table by myself, with a cheap drink, coffee or lager, in front of me to justify my presence, my head resting in both my hands, watching the parties of artists and models at the top end of the room. I knew only a few of their names, although I soon got to know them all by sight. They were objects of positive sanctity to me. I never imagined for a moment that anyone noticed me at all. However, it turned out later that they did, and no one was more surprised than I was to find this out. I used to invent stories for myself about their careless, wild, generous way of life. I tried to imagine what it must be like to be made love to by one of those great men, and I envied the ‘Models who were privileged to sit with them and listen to their conversation (whose probable brilliance soared above all the efforts of my fancy), and, of course, to be their lovers. How I longed to be allowed even a sip from those fountains of wisdom!

I arranged these marvellous beings in my imagination into a sort of order, of which Epstein, with his massive benignity and his mild eyes, was the topmost point. They became part of my life, and although I did not actually pray to them, they were as important to me as the gods of any religion could be. Augustus John particularly intrigued me. In those days of course he was not the famous man he is now, though even then he was obviously a great man. He always wore a black hat, cloak, neckerchief, etc., and would usually sit without speaking except to give a periodic gruff order for another whisky and soda. Allinson was another who had no fear of the picturesque and dressed invariably in a velvet coat and a large stock. He used to play the piano marvellously with his long, sensitive fingers, and he had a wonderful white horse on which he would sometimes ride back to his house in the early hours of the morning. He was also said to possess a wonderful Chinese bed of incredible value. And Roger Fry, the art critic, Nina Hamnett, whose drawings are now becoming famous—a very good one of me by her is reproduced in this book—Bomberg, with his great head of red hair, his red beard, and big blue eyes, Ian Strang, J. D. Innes, Rowley Smart (later an old friend of mine), Odell, to name only a few, helped to complete the picture. All the medical students in those days used to wear side whiskers and big, black, floppy bow ties. One of the most amusing of them was Barry Hyde. Afterwards he became quite a celebrated doctor, but he is now dead. The handsomest of the models was, in my opinion, Lilian Shelley. And above all there was Horace Cole, the great hoaxer. His practical jokes have now become so famous that he is almost a legendary figure, but he does really exist and is still to be seen. Most of his hoaxes are world-famous, but you will remember how he was received by the officers and men of a famous battleship with full naval honours under the impression, created of course by himself, that he was an Eastern potentate. On another occasion he and some friends arrived in Piccadilly dressed as workmen, and proceeded to pick the road up, in which condition it remained for some time. Another time he had a certain very famous person arrested for stealing his watch, to that famous person’s great surprise. In fact, there is no end to the stories about him.

Now I have told you of my distant, day dreaming adoration of these Bohemian divinities you will find it easy to feel the rapture, the ecstasy of joy and fear that I felt when invited to go over and join them at their table. I was sitting, as I have described, with my chin cupped in my hands and my remarkable face framed in my black hair, alone, an intriguing object I suppose, in a way, when to my amazement and consternation I saw Epstein look at me, get up from his place, and walk towards me. At first I thought he must be going to speak to a friend at some table behind mine, but no; he held undeterred on his course. He was really coming to Me. I was too frightened to smile or to say anything polite. I could only stare at him. But as soon as he spoke my fear departed.

“You’re very young to be here, little girl, aren’t you?” he said, and I smiled trustfully back.

Then he asked me to come and sit at his table. You can imagine how delighted and excited I was. Of course after that I met everybody of any importance at all who came to the Café, as Epstein knew absolutely everybody there was to know. And this was the manner of my introduction to the Bohemian fraternity.

For about a year I played the part of the baby and mascot of the Café Royal set. I sat for several artists, but not for Epstein, who thought I was not yet developed enough to be interesting as material for his particular style of modelling. And I did some of my songs and dances at the Cabaret Club, or as it was called later “the Cave of the Golden Calf,” our usual resort after the Café Royal, the proprietress of which, Madame Strindberg, was one of the most remarkable characters of those times.

It was here that I met a charming man whom I will tell you about. Some people will remember him, as he was quite a character I afterwards discovered and was to be seen everywhere.

I had just finished a song there one night and was resuming my seat amidst applause when I found myself being spoken to by an old gentleman whose clothes and appearance seemed very unsuitable for the Cabaret Club. The dress of St. James’s Street looked very odd in front of Epstein’s very funny frescoes on the walls of the club. But he gave no sign of embarrassment, and drank beer out of a china mug as easily as if it had been vintage port or Napoleon brandy. His assurance won my admiration. He had followed me, it appeared, from the Café Royal out of wonder at my extreme youth. I was delighted with him, and gave him a not entirely untrue account of my life, remaining none the less very strictly on my guard. I christened him “the Cherub.”

After this he became very persistent in his attentions, but our relationship was that of father and daughter, with which he appeared quite satisfied, and gave me, I must say, first class entertainment. We used to dine together nearly every night, and he took great pains to educate my taste in food and drink, of which he was a great connoisseur. I was told that the sauce we were having to night showed up the deficiencies of the one we had had the night before, or that the soufflé nowhere approached the one of ten days ago. And quite as subtle were the distinctions I was urged to appreciate between the various wines. Like a pupil in music, I strained my intelligence to remember all these things, and at times almost persuaded myself that my taste was as refined as that of my host, which was of course impossible, as my palate was untrained, and from inexperience I had no standards of excellence to refer to for comparisons.

I now see that he thoroughly enjoyed all this pretence and probably exaggerated tremendously to see how far I would really go in pretending to agree with him and air my own knowledge.

But for the mere matter of pleasure I am convinced that I enjoyed what I ate quite as keenly as he did, though for less good reasons. Or rather I should have done so had I not feared that, being ignorant of what food ought to taste like, an admission of pleasure might be a confession of vulgarity. It was unlike me to admit any rules other than my own preferences, and I soon defied one of my tutor’s most sacred beliefs. In England, as you know, good champagne is dry champagne, and the sweeter varieties are considered fit only for women and Frenchmen. I happen to prefer it sweet. I know it is bad taste, but I cannot help that. I still prefer it sweet just as much as I did in those days. So one night in the Café Royal when we were drinking champagne of especial dryness in honour of some occasion or other, after taking a preliminary sip I commanded the astonished waiter to bring me some sugar! He protested, but I was firm, and beneath the outraged eyes of the Cherub I deliberately dropped first one lump, and then, having tested the effect, another, into the holy fluid. The monocle clattered against the shirt front at each successive blasphemy.

My time was not, however, entirely taken up with the Cherub. I had made another more exciting acquaintance at the Endell Street Club. He was pale, dissolute and smartly dressed, and usually wore several rings on the fingers of his unexpectedly large and powerful, but at the same time white and wellshaped hands. I was attracted to him by his skilful dancing, his garish accounts of life in foreign cities, his lithe brutality and the fear he inspired in everybody, not excluding myself. He was known in England and on the Continent as “Pretty Pet.” I knew he had a very bad reputation, but no one seemed to know anything definite about him. It was not known how much money he had or where he got it from, but he always seemed to spend a good deal. He was a mysterious figure.

I used to dance with him at the Endell Street Club nearly every night, shamelessly cutting my engagements with the Cherub. I was fascinated. And when he asked me to go to Bordeaux with him I agreed without a moment’s hesitation. He told me he could get me a job as a dancer. Now, I thought, I am going to see life.

We embarked at London Bridge in a tramp steamer, and arrived at Bordeaux three days later, having been delayed by fog.

The Old Cafe Royal. By Adrian Allinson.

CHAPTER III

FRANCE

Bordeaux—I dance at a café chantant—I fight with Pretty Pet and leave him—I am taken on as a professional dancer—The Apache—I go to Paris—The Apache gang—I fight with Hortense—“Tiger-Woman”—I fight with The Strangler—The methods of the gang—The branding—The gang is dispersed—I return to England.

I remember that snow was falling hard when we landed at Bordeaux harbour at 8 a.m. I had eaten practically nothing while we were at sea, and was almost fainting with cold and weakness. My unsuitable and very insufficient clothing was wet through and clung tightly to my wincing flesh. Added to this, the captain of the tramp steamer had told me that Pretty Pet was a bad hat. I had no money to get home with, and I was still a mere child.

We went to the Hotel Montre, where Pretty Pet engaged two adjacent rooms with a door between. I had a hot bath and some food and rested while my clothes were being dried. By evening I was feeling much happier and went out with Pretty Pet to a restaurant for dinner and afterwards to a café chantant. Here we sat for a time drinking absinthe and grenadine and watching the performers on a small stage at the far end of the café. This I enjoyed. I have always loved watching anything like a cabaret. And then it suddenly occurred to me that I should like to take part in it. I thought about it for some time, feeling rather shy of suggesting it. At length I asked if I might do a dance. Permission was granted and I went up to the stage and danced as I used to dance for the sailors on the Thames. And as I used to at the Cabaret Club. I still had had no lessons, but no one seemed to mind that. Everybody enjoyed watching me dance. I was a great success. I was recalled time and again and given a great many drinks. After I had finished we returned to the hotel and I went to bed feeling very tired.

I had, however, only just switched off the light when the partition door opened and Pretty Pet walked in. Inflamed with drink and leering with befuddled lust, his unattractive countenance (which had, by the way, earned him the title of Pretty Pet) looked unutterably repulsive. I think I took the situation in pretty well. I at once switched on the light and made for the dressing-table, where I had left my nail scissors, a flimsy enough weapon in all conscience for defence against a desperate White Slaver—for this I had discovered was my cavalier’s profession—but it was the best available and proved in my hands sufficient for the purpose. Pretty Pet was too drunk to see me pick up the scissors, which I grasped firmly in my right hand, the points protruding between my first and second fingers, and the handles pressed firmly against the ball of my thumb—and came at me with careless eagerness, not knowing that I had a weapon. I easily eluded his first clumsy attempt to get me in his arms, and ducking, struck upwards and buried the scissors an inch deep in his wrist. Sobered and riled by the pain, he attacked me in real earnest. He clasped me round the waist, pinning both my arms to my sides, and pushed me towards the bed. I struggled with all the strength that fear and hate could give me. He was, of course, much stronger than I was, but I am so small and wiry that he found it difficult to get a proper grip of me and I kept on wriggling out of his clutches. No one in history can have fought more desperately than I did to escape the Pretty Pet. With a supreme effort, just as I felt the edge of the bed against me, I succeeded in half freeing my right arm so that I was enabled to dig my scissors into the fleshy part of his neck. The pain made him relax his hold for a moment, and seizing the opportunity I hit him as hard as I could on the point of the jaw. He fell, and I dashed over to the fireplace (which I had not been able to get at first because he was between me and it), and fetched a pair of tongs, with which I hit him about the head once or twice to keep him quiet. I then told him that if he moved or spoke I would smash him properly. The threat took effect, for although I made myself comfortable on the bed he did not stir all night from where he lay.

The next morning I ordered him to get back to his own room, and when I had dressed and packed the few things belonging to me I left the hotel and went out into the streets of Bordeaux, speaking practically no French and possessing no money at all. That was the last I saw of “Pretty Pet,” but I believe he is dead now. He seems to have died just as much a mystery as he lived, no one knowing who he was or where he came from.

But what a fool I had been! I was so pleased by my victory that I had entirely forgotten to get any money, and now it was too late. As the day wore on my remorse, added to by hunger, became increasingly strong.

Turning the situation over in my mind; I decided that I must immediately set about finding some employment and a lodging. The first likely plan that came into my head was to apply at the café chantant where I had been such a success the night before. An excellent plan, but alas! I had entirely forgotten the location of the café and was doubtful whether I should be able to recognize it even if by good luck I should happen upon it by chance.

My hunger, however, had to be satisfied, and I went into the first café I saw and boldly ordered coffee and rolls. When the time came for me to pay I told the proprietor that I had no money but offered to work for my meal, and asked him if he would take me on permanently. I will not tell you exactly what he said, but he did not leave me in any doubt as to what he meant. He got an answer he did not expect. I was so angry that I marched indignantly out of the café.

I had walked half the length of the street feeling pleased with my retort before I remembered that my recent way of getting food could not be repeated indefinitely, and that I had as yet found no place wherein to spend the night. I racked my brains to recall something of the appearance of the café I was looking for, and of the features of the street in which it was situated, but without success. I had relied too much on Pretty Pet’s guidance. In this repentant frame of mind I stopped and got a clear picture in my mind of the street I was in, with the intention of using it as a starting-point for my further explorations of Bordeaux, which I set out upon at once, reflecting that, lacking as I did money and friends, I had the greater need of such knowledge as I could get hold of. I particularly noted, in addition to the main streets of the town, the bypaths and alley ways, that might prove valuable for throwing off the pursuit of either apaches or gendarmes, or even my late admirer.

I continued my searching until I was too tired to walk further, and then returned into the first café that met my eyes. I wondered what on earth I could do. There seemed absolutely no hope of finding anywhere where I could so much as lay my head for the night. Much less get a job. I could not of course pay for a drink, but I could at least sit down until I was turned out, and besides—in spite of my previous experience I had hopes that I might meet with some kindness.

All cafés, to be sure, bear a family resemblance to each other, but I felt somehow as if I had been in this one before . . . . It wasn’t? . . . Could it be? . . . There was the stage—the proprietor . . . . It was! All my troubles were at an end. I rushed up to the proprietor, a kind-looking old man, and said,

“I’m the little girl who danced here last night.”

He looked at me, puzzled, and remarked, “Comment?”

“Qui avait dansé,” I replied, and gave a brief demonstration.

“Ah, qui!” he exclaimed and clapped his hands.

He was overjoyed to see me again, and gladly agreed to my proposals, made in awful French, helped by much gesture and illustration, that he should take me on permanently as a—dancer and general help.

I was given a meal and allotted a bed in the same room as his little daughter. This was, of course, an amazing stroke of luck. It is this sort of thing that makes me believe in Fate, and from what followed you will see that I have good reason to.

That night my dancing met with even more success than it had the night before, and my delighted employer very kindly gave me a glass of wine to refresh me before I should be called upon again. I drank only half of it before responding to the clamour of the audience, who insisted on an encore. This time I sang to them in English, for I knew no French songs then—song after song, “The raggle-taggle gipsies,” “The Bonny Earl o’ Murray,” “There lived a girl in Amsterdam,” which I had learned at the Cabaret Club just before I left England, “There was an old woman who lived by herself—all in that lonely wood,” a nursery rhyme that I had known all my life, and as a final encore, “I know who I love, but the De’il knows who I’ll marry,” a song which I have always felt a great affection for.

It was at this point that a thing happened which was to alter the whole of my life. It was entirely unexpected and it took such a short time to happen, and events followed in such quick succession, that before I knew where I was my whole life had once more altered completely.

Returning to my table I was surprised to find seated there a man whom I must pause to describe in some detail, as it was through him that the course of my life for the next year was to be diverted in a most astonishing direction. The first and only thing that comes into my head to compare him with is a sewer rat. He had the same appearance, and gave the same impression of narrow-headed meanness and viciousness. What the comparison does not convey is his air of vanity and bravado. He wore a seedy black coat, cut in the usual high-waisted French style, with the collar turned up, dark blue trousers, pointed brown patent-leather boots, a scarlet neckerchief, and a light grey cap with a large peak. He was short and slim—I should put his height at about five feet seven. His eyes were black and beady, like those of a rat, and his yellow skin was stretched tightly over the bones of his face.

“A stage apache,” you will say.

“A real apache,” I reply, “and therefore an actor.”

I was to get to know this in the future. Men who looked as if they were merely dressed up to look like dangerous characters were actually dangerous characters and used their appearance to terrify those whom they thought would be useful to them or whom they blackmailed.

I smiled at him before sitting down, but his features gave no evidence that he had perceived either me or my smile. I took up my glass and was about to drink with no further thought of this surly youth when, before I could convey it to my lips, he dashed it from my hand.

I slapped his face. There was dead silence, then an uproar. His expression was the embodiment of every sneaking, spiteful, cruel, vicious, revengeful passion.

I withdrew under cover of the commotion to a remoter table. But I felt his wicked little eyes follow me through the press. I felt them sticking into my shoulder-blades like red hot pins. Turning my head, I saw he was still intently eyeing me, and looked away with a shudder. The red hot pins again lodged in my shoulder-blades. Which was worse—to look upon him, or to feel him behind me like a fiend about to jump on my back? I could not decide.

For an hour I sat looking at him and away and at him again, and all the time his eyes neither blinked nor diverted their gaze from me for a second so far as I could observe. It was a nerve-fretting experience. At length, like the heroine of a novel, I felt that if I were subjected to this strain a moment longer I should scream. So I walked out of the café, keeping my eyes from him with an effort, and turning either to the right or the left (I forget which), I hurried away as fast as I was able. But in a few yards I knew that the fiend was pursuing me. I started to run, hoping that I could make one of the side turnings I had previously explored. But it was no use. I felt my left wrist roughly grasped and a voice hissed in my ear, “Come with me. You are what I want.”

I wondered if he was going to kill me. After all, I suppose he could easily have done so if he had wanted to. Certainly no one in the café would have taken any steps to prevent him doing so. They were all much too terrified.

I went, for I had no choice. My captor then proceeded to explain, though owing to my ignorance of the French language I was unable to follow his meaning at the time, that he was the leader of an apache gang in Paris, and that he was known as White Panther on account of his silent and deadly assault in street robbery. All this he told me with the pride of a nobleman of ancient family proclaiming his lineage.

I supposed that only my admiration could make up for the insult I had delivered to his vanity, and only my praise could revive his self-esteem.

It was with this man then that I went to Paris. Things had taken a strange turn, as you see.

The headquarters of White Panther’s gang was a cellar in the heart of the Glaciere district, where the police go in pairs by day and not at all by night. At first sight it reminded me somewhat of my native Canning Town, although I am bound to admit that it appeared one degree at least more squalid and much more dangerous. From the station White Panther led me so swiftly and by such a winding route that in spite, of the most earnest attention to where we were going (in accordance with the resolution I had recently taken in Bordeaux) I soon lost absolutely all sense of direction. Gradually the alley ways became narrower and more numerous and impossible to remember, until I almost felt that I was in a warren constructed by some animals and not by men at all, rather than in part of a city laid out by human beings.

On every side ill-fitting shutters permitted slips of light to escape. These to my heated fancy were like tongues of Hell-fire.

Suddenly White Panther stopped outside a deserted-looking house and knocked in a particular way upon the basement door. We were admitted, and I found myself in a long room with a bar at one end, behind which stood the fattest man I have ever seen. The floor was scattered with sawdust. Spittoons were arranged round the edges, and deal tables dotted about in the middle of the room. The room was dimly lighted by a couple of hanging oil lamps. This turned out to be the chief living room of the gang. It was here that everyone met and where plans were made. It was also, as you will hear later, the scene of several fights.

A number of men and women, dressed in the picturesque apache style, were drinking at the bar. Still holding my hand, White Panther led me towards them. The conversation dropped at our approach.

“Hortense,” called White Panther.

At this a dark-eyed girl, with beautiful pointed breasts, stepped forward and looked at us for a moment. Her face darkened with anger, and before White Panther could explain who I was, she rushed at me, whipping out a knife as she came.

It was a sudden rush of jealousy. I do not know what the White Panther thought was going to happen. Possibly he only wished for a fight just to see which was the best of us. If he did, he narrowly missed losing me altogether.

I was unarmed. It was an unpleasant situation. As she lunged at me I jumped back, and raising my hands, warded off her blow at the expense of a slit palm. Then before she could recover her balance I managed to leap upon her and wrenched the knife from her hand. I could have killed her, but this was the last thing I wished to do. All I wanted was to protect myself now and in the future, and I felt that I must show this as violently as possible. I therefore flung the knife away and attacked her on equal terms with my bare hands. Unarmed, she was no match for me. Seizing her hair in one hand and her cheek in the other, I flung her on the ground and smacked her face, methodically, with my clenched fists. I blacked both her eyes, I knocked her nose from side to side, causing it to bleed profusely, but without breaking it. I beat her lips against her teeth till her mouth was full of blood. Indeed by the time I had finished with her I should doubt if there was a single square centimetre from hair to chin unbruised. I must say that I was in a frightful passion. I was just administering a few blows to a spot which seemed lighter in colour than the rest when White Panther dragged me by the hair to my feet. In an instant my teeth had met in his wrist just below the coat sleeve.

“Tigre,” he muttered. With a blow he knocked me staggering across the room. But from that time I was known among the apaches as “The Tiger-Woman.”

I now definitely became a member of the gang. There was really nothing else for me to do. Besides, I enjoyed this life of adventure, and I must say that on the whole everybody was very kind to me. Of course there were rather awful moments, some of which I will describe, but being one of them I had to live their life and get money by their methods. If people are shocked by this part of my story, I ask them to recollect what were the circumstances I found myself in when I got stranded alone in a foreign country.

All the men of the band carried knives, which they used among themselves at the slightest provocation, and there were always being fights as a result.

Among other people I met while I was in Paris was the notorious Mlle Bertrande, who was sentenced a few years ago to a very heavy term of imprisonment. At that time she was a very well-known figure in the underworld.