|

THE SUNDAY EXPRESS London, England 4 March 1923 (page 1)

YOUNG WIFE’S STORY OF CROWLEY’S ABBEY.

SCENES OF HORROR.

DRUGS, MAGIC AND VILE PRACTICES.

GIRL’S ORDEAL.

SAVED BY THE CONSUL.

THE GIRL-WIDOW

With a full sense of the responsibility involved, the “Sunday Express” to-day publishes the story of the young wife who has just returned from the “Abbey [of Thelema]” of Aleister Crowley in Sicily.

Last Sunday we told of the death of the girl’s husband, a brilliant scholarship ‘varsity graduate. For the sake of the lad’s parents his name was withheld and is to-day.

SINISTER FIGURE.

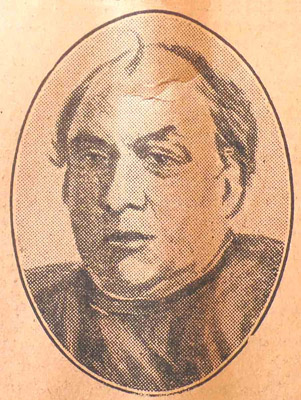

This man Crowley is one of the most sinister figures of modern times. He is a drug fiend, an author of vile books, the spreader of obscene practices. Yet such is his intellectual attainment and mental fascination that he is able to secure reputable publishers for his works and attract to him men and women of means and position.

The young wife is known to the artistic world as “Betty” [Betty May]. She married her husband [Raoul Loveday] when he came down from Oxford.

Shortly after they met Crowley. Her husband, like many other undergraduates, was interested in magic. Crowley [illegible] him. He offered the young man a position as private secretary at his “abbey.” The wife fought against it, but finally accompanied her husband there.

ABBEY VISITORS.

Her experiences comprise a sensational and dreadful accusation against the infamous creature known as “The Beast.”

Crowley has arranged with several Oxford men to go to his “abbey” in the spring. The “Sunday Express” urges the proper authorities to see that the truth is revealed to them.

The “Sunday Express” wishes to point one thing out—in all the sordid story there is nothing to be said against the character of the young husband. He was the victim of a dreadful mental fascination only.

THE GIRL’S STORY.

We reached Cefalu—a tiny town of one narrow street and a few houses straggling up the hillside. Lovely indeed, but desolate.

No one met us. It was eight o’clock on a Sunday evening, dark and cold. We inquired if any one knew Crowley. Conversation was difficult. Some of the Sicilians spoke a little bad American; and my husband spoke a little worse Italian. But the name Crowley acted like a charm. They all knew “The Great Beast,” as they call him; and half a dozen set out to guide us.

It was a long, dreary climb up a muddy, mountainous path; and our first glimpse of the “abbey” did nothing to dispel my forebodings. It loomed up suddenly before us, the white house gleaming eerily in the faint moonlight, one mysterious, flickering light shining from a small window.

LIKES HIS NAME “BEAST.”

Our reception was startling enough. We knocked at the door. It was opened by a woman, whom we were to know as Jane [Jane Wolfe].

“Beast,” she cried out, “here are Mr. and Mrs. ———”

I was, of course, amazed: but we learned afterwards that “Beast” is Crowley’s own name for himself. He likes it; and certainly no other name could be more appropriate.

Crowley appeared. He raised one hand above his head, and said:—

“Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the law.”

To which half a dozen other voices replied:—

“Love is the law, love under the law.”

* * * * * *

Tea was prepared for us. I sat silent, feeling very cross and very low-spirited. The tea was bad. Crowley sat in the centre, our Sicilian guides regarding him with awe. He asked us about our journey, and tried to be affable. During tea-time the whole of the household was present, and I was able to take stock of our future companions. We were nine altogether (excluding the Sicilians). There was Crowley, Jane, Leah [Leah Hirsig], Mrs. S. [Ninette Shumway], three children, Howard [Howard Shumway], Hansi, and Lulu, and our two selves. Presently Crowley said we had better retire early after our journey. No beds were ready for us, so Jane gave up her room to us, and spent the night in the Temple.

The Temple, the scene of the rites and orgies of this unspeakable man and his followers! It is a large room, about the size of a small studio, with folding doors flanked on either side by windows. In the ordinary Sicilian farmhouse this room is the room of the animals, for the Sicilian keeps his donkeys, cows, chickens, and pigs indoors.

* * * * * *

We were awakened at half-past seven the next morning by the banging of a tom-tom, followed by a woman’s voice crying, “Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the law.” And the voices of all the others came from their various quarters, responding, “Love is the law, love under the law.”

This, we found, was the daily morning ritual. We were left pretty much to ourselves this first day, “to get acclimatized.” Indeed, as a general rule, Crowley is not seen by any one before tea-time. He remains in his own room—Cauchemar, or Nightmare, as it is called—drugging himself. His room is full of drugs of all sorts; there is a great bottle of raw hashish, and bottles of cocaine, heroin, morphia, and ether. He distils his own opium, a lot of which is smoked in the “abbey.” Anybody can have whatever “dope” they like by asking for it.

Lunch was at twelve o’clock, and before the meal all the household came out of doors, faced the sun, and, raising their arms, gave adoration, uttering the words “Hail unto thee, from the abodes of morning.”

PENTAGRAM.

At four o’clock my husband and I were summoned to the Cauchemar. Crowley received us, lying on his bed, his totally bald head covered with a black wig. He gave us our instructions. He addressed me as “Sister Sibylline,” and ordered me to do all the cooking and to keep the house clean. He told me I should have a woman from the village to help me—but she never materialized. My husband, for the present, was to play chess and to read with the Beast.

The tom-tom went for tea. This is the time when Crowley gets up and joins his disciples. The fare was salad and coarse, unpleasant bread. Crowley ignored me at this meal, and as I watched the gathering, I turned against them all.

Crowley rose. “Pentagram will meet at 7.30 tonight,” he said.

“What is Pentagram?” I asked.

“You will see,” was the only reply I received.

* * * * * *

Once a day no one is allowed to keep “outside the magic circle.” At 7.30 we all trooped into the Temple, where a circle is marked on the floor. A great charcoal fire burns in the centre. The Beast’s chair stands on the north side of the circle, with a brazier in front of him and six coloured receptacles for his swords and magic wands.

I refused to sit in the circle, and was allowed to remain outside. Incense was burnt before Crowley, who was robed in scarlet and wearing magnificent rings. The women in the “abbey” all wear trousers and shirts. Leah is known as the Scarlet Woman; she was clad in a red robe edged with gold. All the trappings are of indescribable richness.

VILE PICTURES.

Prayers were offered, and Crowley, pointing to each one in the circle with his magic sword, uttered mystic words. Only the Scarlet Woman was omitted from this part of the ceremony, which concludes with a general clapping of hands. The length of the ceremony varies from twenty minutes to several hours; it depends on the amount of cocaine that the Beast has taken. On some occasions his brain is so vigorously excited that he can go on talking for any length of time.

After Pentagram, Crowley told me to go to bed, and my husband to come with him to the Cauchemar for a talk. I went to our room, which led out of Crowley’s. It was many hours before my husband joined me.

The days went on. In the mornings I worked; and gradually I saw things that in the fatigue and excitement of arrival I had not noticed. Vile pictures, some hanging on the walls and others engraved on them, horrified me. Tea became an impossible meal for me, the conversation was too sickeningly bestial. Crowley is, I should think, sexually mad; he sees and talks of nothing else. Time after time I used to leave the table; generally I was fetched back. It was a dreadful ordeal: silence for lunch, filth for tea.

He was “initiated,” but he would never tell me anything about the ceremony. All I know is that he wore gorgeous robes, that the ceremony lasted eight hours, and that he was presented with a guinea book—for which he was supposed to pay.

Now I come to the sickening episode of the cat. By this time Crowley never spoke to me; all my orders came from Leah. At tea one afternoon Crowley was in a most peculiar mood, irritable and uneasy. Suddenly he rose and said, “There is an evil spirit in this room.”

I felt annoyed. “Oh, do sit down, man,” I said. He sat down, and noticed a cat sitting by his seat—a lovely, tortoise-shell animal. Crowley went to pick it up; the cat scratched him viciously on the arm, and wriggled from his hands.

“Within three days,” ordained the Beast, “that cat must be sacrificed.” Then a very remarkable thing happened. Crowley came into the kitchen and saw the cat sitting by the window. As a rule this cat would run away if any one came near it; but Crowley approached it, made passed with his “magic sword,” and the cat never moved. It was probably hypnotism, but it was uncanny.

“THE BEAST” (Kramer’s [Jacob Kramer] painting of Aleister Crowley).

THE SACRIFICE.

The third day arrived. I wanted to get the cat away, but my husband told me not to interfere. But I took the animal a long way from the house, and put it down, saying, childishly, perhaps—“Stay there, pussy, if you value your life.” But it followed me back.

Crowley had told my husband that he must kill the cat, and to write out an invocation. Imagine the effect of such instructions on a highly sensitive man like my husband. He went ashen pale and trembling as he heard the words, but the Beast’s influence over him was such that he could not refuse. He caught the cat, and put it in a bag. The animal cried pitifully.

The hour arrived. I refused, as always, to sit in the magic circle, but insisted on being present. I took a seat close to the door, so that I could escape if I wanted to.

The altar was dressed for the occasion with “Cakes of Light.” It is impossible to describe of what these are made. I do not believe any normal mind could ever imagine the ingredients.

Above the altar hung a bell, formed of an almost flat metal disc, the striker being a human bone. A bowl to catch the cat’s blood stood at the side.

My husband, trembling from head to foot, stood by the altar, armed with a kukri—the sharp, carved sword that the Gurkha finds so effective. He had to lift the cat in one hand, and kill it with the other. The cat struggled violently. Crowley dabbed it’s nose with ether till it became quiet enough to hold.

KILLING THE CAT.

The reading of the long incantation concluded. “Now,” said the Beast. My husband struck at the wretched cat, but his blow lacked force. He only half killed the poor animal, and dropped it. The cat, pouring blood from its throat, dashed away into Jane’s room, leaving a red trail behind it.

Crowley ordered me to fetch it back. I refused, so he went himself. My unhappy husband was forced to pick it up again, and, finally, with another hard blow, severed the cat’s head from its body. The body fell to the floor with a thud that I can still hear.

Jane hid the body of the cat—which happened to belong to our nearest neighbor—and threw it in the sea the following day.

Other incidents and practices indulged in at the “abbey” it is impossible to describe. They are too terrible.

With every day my horror and repulsion grew; my sense of foreboding, too, increased, but we could not get away. We had no money. Then one day I woke up feeling giddy and feverish. I could not work. I was sick, and ultimately I collapsed. I asked for a doctor. One came, and said that I was very ill. He treated me with skill, and soon I recovered.

MAGIC DIARIES.

Just as I was getting better my husband was seized with enteritis. “You are eating too many oranges,” I told him, but it was something more than that. He became very weak, and was always cold. He even grew too feeble to write his own letters, which he asked me to do for him.

In desperation I wrote to his mother telling her how ill her son was, but begging her not to let my husband know I had written her.

In the meantime my husband got steadily worse. He was always cold—so cold that he would get into bed with his clothes n. At first Crowley refused to let a doctor come to see him, but eventually one did come. But my husband did not improve. He had remarkable sudden pallors. He head and hands would go white. He had no energy. He even gave up writing in his magical diary.

While my husband was lying ill, Crowley decided that his head must be shaved. The Beast himself acted as barber, and shaved my poor husband’s head of every hair, also inflicting a horrible cut on his head. His arms too, were full of cuts; for every time one uses the word “I” in the “abbey”,” one has to inflict a cut on one’s own arm.

If my husband’s body could be exhumed it would offer a piteous spectacle.

* * * * * *

Then a most fearful thing happened. Newspapers arrived from England. I was about to read mine, when Crowley suddenly entered the room and said: “No papers are to be read.”

I retorted that I was certainly going to read mine.

Crowley again forbade me. My husband, suffering as he was intervened.

“Don’t be a damned fool,” he said.

“I forbid it,” repeated Crowley. “If she reads her papers, out of the ‘abbey’ she goes.”

Crowley returned a little later, and found me reading my newspaper. It was the number of the “Sunday Express” containing the astounding revelations of Crowley’s career. It had been published, of course, weeks ago, but had only just reached Cefalu. The revelations horrified me. I saw Crowley looking at me, and was afraid to say anything. He too said nothing. At teatime nobody addressed me. I had been sent to Coventry, and could feel the atmosphere of impending disaster.

TURNED OUT!

At eight o’clock—Pentagram time—Leah brought me a message from Crowley, ordering me to go to him.

I refused, saying that I was nursing my husband.

Crowley himself came to me. “Pack up your boxes and go,” he commanded.

My husband, from his bed of sickness, begged Crowley not to insist.

The Beast seized me by my wrists, dragged me to the door, and threw me out. I threatened that I would go to the British Consul. Crowley laughed: “What can you do?” he sneered. “Look at all my witnesses in the ‘abbey’ here—what is your word against all of theirs?”

* * * * * *

Then began the most fearful night of my life. I was frightened almost to death. Out in the hills, in a strange country, and penniless. Below in the little town the peoples were holding a carnival dance. Their laughter came up to me through the still night air as I stood helpless and shivering on the bleak hillside.

I made up my mind that I must go to town, and I reached Cefalu as the townspeople were going home from their dance. It must have been a queer sight, the dancers in carnival costume, and myself in my working clothes, my hair blown about by the wind, and my cheeks stained with tears.

Then a man who sometimes came up to the “abbey” saw me, and asked me what I was doing there at that time of night.

I told him what happened, “You must go to the hotel,” he said. I told him I was penniless, but he escorted me to the hotel, where the magic words, “Inglese Consol,” proved a talisman, and I was offered a room. But I was afraid to go to bed. I sat on the edge of the bed all night, fearful at every sound.

The next morning I wrote to the British Consul at Palermo, telling him the whole truth that had led to my desperate position. Hardly was the letter written than Jane arrived with a note from my husband. It had not been difficult to find me. By breakfast time all Cefalu knew that I had been found wandering in the street in the small hours.

My husband’s note said that he was very ill, and that the doctor was coming up. This news was enough for me. I rushed back to the “abbey.” I saw my husband. He looked dreadfully bad.

“What is it, darling?” I asked.

“Ask Crowley to let you come back,” he said. I looked at his pale, worn face, and didn’t wait to ask, I walked in.

“HE’S GONE.”

Before Crowley would consent to my remaining at the “abbey,” he compelled both myself and my husband to sign a document, declaring that I had taken drugs before coming to the “abbey.” It was the only means of remaining, so I agreed; my husband objected, as he couldn’t see what was written on the paper. But eventually he agreed: and this document Aleister Crowley sent to the British Consul.

Meanwhile the doctor had gone, promising to send up the medicine. But the medicine did not come until it was too late. I was desperate, and hardly knew what to do. In my despair I gave my husband an injection. He was very, very cold; the coldness of death is very strange.

“Are you comfortable, dear?” I asked him.

“Yes. I do love you, darling, I do love you.”

These were the last words my husband ever spoke to me.

* * * * * *

To my amazement I was asked to go to the town to buy an article for the sick room. I hurried off, and when I reached Cefalu I fainted in the street. When I recovered I was seated on a chair in front of a house, while somebody was holding a glass of water to my lips.

Suddenly I saw Crowley coming down the street.

“I heard you had fainted,” he said. “You must come with me.” He seemed strange, his pallid, blotched face looked more unhealthy than ever. He called for the doctor, hired a cab, and we drove to the “abbey.”

At the door Crowley alighted. With raised hand he stood before me.

“Adoration,” he said.

“Oh, do be quiet,” I cried.

Jane stood in the doorway. “He’s gone,” she said. I laughed. “Where?” I asked.

“He’s dead,” she replied.

* * * * * *

I remember nothing till six o’clock—two hours later. It is a regulation in Cefalu that no dead body may remain in a house after seven p.m. It must be removed to the “Greenhouse.”

“I must see my husband,” I said. They took me to him. By the light of a candle, in the duck I saw him. He looked so peaceful, so comfortable, this brilliant, lovable husband of mine, whose life had been so uselessly thrown away—

They would not leave me alone with him. I could not quite realise things even now. “What is that box for?” I asked. It was his coffin. I did not know what to do. If I could have found Crowley’s gun I would have shot the Beast. But I could not find it; and later all my energy left me. I collapsed utterly. Leah induced me to go into the open air, and gave me some brandy; Crowley gave me veronal to make me sleep.

Next day a wire came from my husband’s mother asking us to bury her son in the Protestant faith. “Any faith other than Roman Catholic is Protestant,” said the Beast.

They tried in vain to keep me from the funeral. The Beast wore his funeral robes; all the women too, wore robed. The coffin stood on trestles beside a hole in the ground. Crowley tapped the coffin with his wand. The whole of the Pentagram Service was performed; it lasted an hour and a half.

Then I rushed to Cefalu. I must somehow or other send a telegram. But I had no money. A wire had been sent to my husband’s parents previously asking them to telegraph “fifty pounds sterling.” But they regarded this telegram with suspicion, and rightly. I would certainly not have used the word “sterling”—“pounds” are just pounds to me, and that is all I should have said.

But while I was trying, in dumb show, to persuade the postmaster to send a telegram for me, one arrived from Palermo for me. It was in reply to my letter to the British Consul, and he had sent me fifty lire that I might come to him.

I flew back to the “abbey.” Escape—that was my one thought. Crowley who had avoided me up to this, now came to me.

“You will make this your home,” he said. “This is your life. You have no money.”

IN LONDON.

I replied, “I will go. I have money. The British Consul has sent me fifty lire.” I clutched the money, afraid of losing it.

“Jane is going to London shortly,” he retorted. “You will be back here in three months.”

Such is the astounding power of this dreadful person that even now, back in London, I feel uneasy at his words. But I would not let him see my feelings.

“I’m going,” I repeated. He turned to Leah. “Keep he here at any cost,” he commanded. “She is to stay, Leah. I charge you!”

I turned and dashed for the door. The Beast saw I was going. He laid one finger on his lips, and said in a tone half of advice and half of menace:—

“Silence, you understand?”

* * * * * *

My meeting with the British Consul at Palermo was like going from death to life. To be with this courteous, kind Englishman after my experiences with the devilish inmates of the “abbey” was a wonderful experience. I told him some of my adventures: he guessed more.

If my revelations of the life at the “abbey” in Cefalu can help in any way to put a stop to the infamies of Aleister Crowley, and prevent others from becoming his dupes, my husband’s life will not have been given vainly, nor will my sufferings have been wholly useless.

It is all so recent, and yet it all seems so far away—as if it had happened in another life, or in a nightmare.

But I have had a reminder that is it true. On Wednesday I went to see an acquaintance, and in her house I saw—Jane. She has already come to London: what will be the next move of this emissary from the Beast?

The sight of her has frightened me. I have told my story to the “Sunday Express.” I hope the widespread publicity will act as a deterrent to Crowley and his friends, and as a safeguard to me. |