|

THE ST. LOUIS POST-DISPATCH St. Louis, Missouri, U.S.A. 14 December 1930 (page 4, 7)

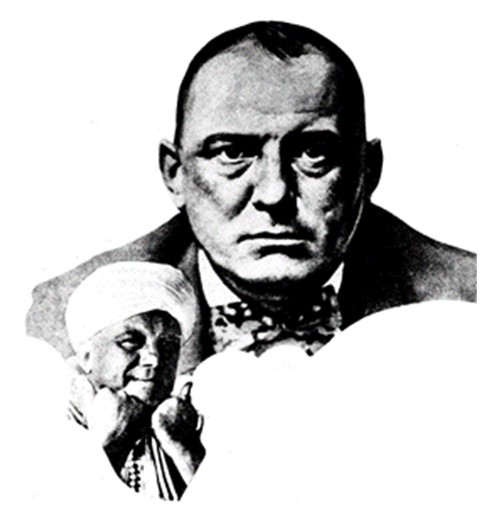

They Called Him the “Wickedest Man in the World.”

While a British Writer Was Demanding Fair Play for Aleister Crowley, the Poet Himself Was Staging Another Eccentric “Disappearance.”

Aleister Crowley and in Ritualistic Headdress and Robes.

The “wickedest man in the world” has still another black mark against his name. It was a London newspaper that conferred on Aleister Crowley this unenviable distinction and in his latest exploit his detractors profess to see just another tribute to his so-called villainy. Crowley—author, mystic, world traveler and explorer—recently became involved in a strange incident at Lisbon, Portugal, according to reports which have just reached London. He was stopping there, it is said, with a young girl, reported to have been a Californian, a student in a Berlin art school. The two had a row so violent that reverberations of it reached the police.

The girl left in a huff for Germany, but not before Crowley had perpetrated what was apparently another of his strange jokes. On the seashore, about 20 miles from Lisbon, where the water rages so fiercely between two great rocks that the place has been called “Boca do Infierno”—the mouth of hell—was found a note that said in English: “I cannot live without you. The other ‘Boca do Infierno’ will get me—it will not be as hot as yours.” The note was signed “Hisos,” accompanied by a cryptograph. It was weighted down with a cigarette case, singularly ornamented, similar to the one that Crowley was known to have carried.

All indications pointed to suicide, and for a time the European press too this view. But the Lisbon police were laughing, for they know that Crowley, safe and sound, had left Portugal on a regular passport for Spain.

Letter found on the edge of an abyss near Lisbon and supposed to have been written by Crowley.

The curiously ornamental cigarette case which was holding down the so-called farewell letter.

Ironically enough, this comes at a time when a definite move had taken shape in England for an honest appraisal of Crowley’s life and writings. Some time ago a book appeared in his defense called “The Legend of Aleister Crowley,” written by P.R. Stephensen. This in itself, in the definition of the man biting the dog, was news. For probably no one in this century has been subject to so persistent and so virulent an attack as Crowley. Every possible variety of derogation has been slung at him in long campaigns in the more sensational press.

He has been accused of every crime in the catalogue, from cannibalism to high treason. The principal papers to attack him, the Sunday Express of London and John Bull, have not hesitated to impute to him every unnatural and perverted vice, all the sinister and unmentionable sins. They have pictured him as a fiend incarnate, practicing the black mass and other orgiastic rituals. They have strongly hinted that he plotted the murder of a friend in order to place the man’s wife in his power. There has been absolutely no limit to which they have not gone.

And Crowley never replied in any way whatsoever. Stephensen, in his defense, says that Crowley always felt the futility of any action against these powerful publications, maintaining that their legal staffs were so strong and their resources so ample that it would be almost useless to bring suit for libel. Furthermore, he was quite philosophic about it, believing that in the end these campaigns of vilification would defeat themselves by their very exaggeration. And this was in part true, although mothers in England still use the name of Aleister Crowley to make their children behave.

It did become slightly absurd with the cannibalism story. That one was told in John Bull. Crowley is supposed to have been on a climbing expedition in the Himalayas. He started out with two native porters and came back without them. Asked what had happened to his guides on his return some weeks later, he is said to have replied that, running short of supplies, he killed them and ate them, finding his way back alone.

Stephensen, a young London journalist, has been deeply stirred by what he feels to be the rank unfairness of the attack on Crowley. He is a great admirer of Crowley’s writings, is convinced that he has great genius, and that his work will live a long time after his villifiers have been forgotten. He quotes numerous excerpts from the various press attacks and remarks: “There has never been anything like it in literary history—probably because there has never been anything in literary history like modern sensational journalism. How would the Sunday Express have ‘exposed’ Byron? In what terms would they have described ‘Don Juan,’ and with what phrase would they have gloated over his amours? What would have been the results if the private life of Shelley and Keats had been dragged into a Sunday newspaper specializing in moral indignation and invective?”

The author of “The Legend of Aleister Crowley” cites several amusing incidents to indicate how complete is the belief in Crowley’s wickedness.

“The publishers of his autobiography, now in the press, have had some fun,” he writes. “Weird customers have walked into their offices, uttering cryptic warnings and have vanished, leaving no traces of identity. One of them said: ‘Always cross your fingers when you speak to Aleister Crowley.’ His own fingers were crossed all the time he was in the office. He said: ‘That man is superhuman; he can read thoughts; he knows what we are thinking now.’ Questioned, the weird visitor would say no more, but merely withdrew, his fingers still crossed, moaning hollowly: ‘Remember, remember!’ like the ghost of Hamlet’s father.

“Many other kind friends ‘seriously warned’ the publishers and meant well. In discussion, most of them were amazed to learn that Crowley was actually living in England, going about his business as a normal man of letters, correcting proofs and otherwise seeing his books through the press. They were under the impression vaguely, that he would be arrested if he set foot on these shores! Informed that Crowley has never been charged with any criminal offense in all his adventurous life, some replied: ‘Ah, that shows how clever he is!’ The legend persists.”

“I am far from exonerating Crowley himself, Stephensen adds. “A quite extraordinary simplicity in his nature has led him systematically to invite hostility from almost every quarter, as I shall show. He has held nothing ‘sacred’ merely because it appeared sacred. Piece by piece he has alienated that vague mass of dogma called Public Opinion, and outraged it. He has attacked with his devastating humor, precisely those people who have no sense of humor in their doctrines.”

Crowley was born in 1875 of a family of religious fanatics of the repressive Puritan sect, the Plymouth Brethren. His mother usually designated him by the mystic name of “The Beast 666,” which always has perversely pleased Crowley. As a boy and in adolescence his chief hobbies were poetry, chemistry, mathematics and chess, and the sport he liked best was rock climbing, at which he early attained great skill. He was sent down to Cambridge at 20, the possessor of a fortune of $200,000, which he had inherited on the death of his parents. In 1898 his third year in the university, he published five volumes of verse, “Aceldama,” “White Stains,” “The Tale of Archais,” “Songs of the Spirit,” and “Jephthah.” Within 10 years he was to publish more than 30 volumes, most of them privately, and all of them beautiful examples of the printer’s and engraver’s crafts. “His poetry was ‘outrageous’ in the manner of Swinburne, Baudelaire and the Yellow Book. One of his earliest works was a poetic reply to Kraft-Ebing.

He sent his books to the press for review. For a time he lived as “Count Svareff” in a flat in Chancery Lane in London which he fitted up as a magical temple. He bought a Scottish estate at Boleskine, Inverness, and appeared at the Café Royal in full paraphernalia of a Scottish chieftain, as the “Laird of Boleskine.” The Crowley legend began to grow, feeding upon these sensations.

He climbed the soft chalk of Beachy Head, to the complete astonishment of the natives, no less than of experienced climbers. He began making climbing records in Cumberland, in Wales and on the Alps. “A sinister interpretation was placed even upon these feats of agility and daring,” Stephensen writes. “Aleister Crowley was climbing unclimbable places. Obviously by supernatural aid. Inevitably he came to loggerheads with respectability as personified in the Alpine Club, and began exposing its members as incompetents and even as untruthful braggarts. Another hostile group! But merely in passing.”

Crowley took an active part in the controversy over Epstein’s [Jacob Epstein] monument to Oscar Wilde in Paris. When the police refused to permit to be unveiled, Crowley unveiled it by a stratagem “in the interests of art.” The legend grew.

“One would say,” Stephensen observes, “that he was asking for notoriety and he got it. I can think of a simpler explanation—merely in his poetic exuberance, in the fact that he really thought an artistic purpose would be served by shocking the suburbs, and in the fact that he really did not care what people thought of him, because he had enough money to be indifferent to any hostile opinion of criticism.”

“From time to time,” Stephensen says, “he mysteriously disappeared; to reappear eventually in his old haunts, looking years younger, refreshed in body and mind, even more sardonic, witty, vituperative and ‘wicked.’ ”

He traveled to many of the strange and far places of the earth in these periods of absence from London. From 1900 to 1902 he made a trip around the world, stopping for a day, a week, or many months, as the mood and desire impelled him, in New York, Mexico, San Francisco, Honolulu, Japan, China and Ceylon. This trip included six months in the Himalayas with the Chogo Ri expedition of 1902, spending 65 days on the Baltoro Glacier and attaining a height of 22,000 feet. He studied and practiced the Hindu spiritual discipline of Yoga at Ceylon.

The year following his return to London he married the sister [Rose Kelly] of Gerald Kelly, the artist. In 1904 he traveled to Cairo and the same year revisited Ceylon for big-game shooting. In 1905 he went again to the Himalayas on the famous expedition that attempted to scale the Kangchenjunga peak and attained a height of approximately 23,000 feet. In 1906 he went down the Irrawaddy River to Rangoon and later made a walking trip in China with his wife and small child. A part of the following year he spent with certain Arab tribes of Morocco, accompanied by the Earl of Tankerville.

And all this time that he was off in the far corners of the earth his books were appearing. Stephensen says that no one knows their exact number, probably not even the author. His collected Works appeared from 1905 to 1907, one thick India-paper volume each year.

Returning to London for a comparatively long stay, he gave a public exhibition of the Rites of Eleusis. Earlier he had written an essay which “is a passionate statement of the necessity for revitalizing religion,” according to Stephensen. While the ceremonies of Eleusis were held in a public hall, admission was by card, signed personally by Crowley, and only 200 were allowed in. According to published reports in reputable journals at the time, it consisted of music, dancing by robed figures, some incantations, the use on incense and lighting effects. There was nothing shocking or orgiastic about the performance, according to reporters who were admitted to the ceremony.

Certain newspapers took it up in a mild sort of way, but with no personal venom displayed against Crowley. From 1908 to 1914 Crowley published a magazine, that appears twice a year, called The Equinox. It dealt with occult matters. He wrote the entire issues himself. After he published what were supposed to be the secrets of the Rosicrucians an effort was made to suppress the magazine by injunction, but The Equinox appeared on scheduled date, Crowley winning the court fight.

At this time, too, appeared a tribute to Crowley in the form of a book called “Crowleyanity,” [The Star in the West] by Captain J.F.C. Fuller of the Oxfordshire Light Infantry, and now at the War Office. Amongst other thunderous phrases, Captain Fuller had this to say:

“It has taken 100,000,000 years to produce Aleister Crowley. The world has indeed labored and has at last brought forth a man . . . Crowley has twisted a subtle cord on which he has suspended the universe and swinging it round has sent the whole fickle world conception of these excogitating spiders into those realms which lie behind Time and beyond Space.”

Up until the outbreak of the war in 1914, Crowley still had some standing with the public, Stephensen says. Or at any rate he had not violently estranged every element. Shortly after the outbreak of the war—Crowley says he tried to enlist for service but was rejected because of a chronic illness—he went to America. In New York he got in with George Sylvester Viereck, who was then editing a paper of strong pro-German tendencies. Crowley announced himself as pro-German. He proceeded to write violent articles for this paper containing extravagant praise of the Kaiser and Hindenburg, so extravagant that they appear, as he now claims, to have been burlesques, done with the intention of so exaggerating the German cause in America that it would appear ridiculous. All the time, Crowley maintains, he was in league with the British intelligence service. Whether this was true or not, certainly no one in England believed it and high treason was added to the list of the “bad man’s” other crimes and vices. But at any rate he was allowed to return peaceably to England in 1919.

He did not stay for long. He went to Cefalu in Sicily and there in a house fittingly decorated he practiced religious rites similar to those of Eleusis. England took no cognizance of her “worst man,” who went contentedly on cooking little cakes of honey and goat’s blood over ancient braziers, while his small band of followers looked worshipfully on. It was not until Crowley published a novel called “The Diary of a Drug Fiend” that the sensational papers came to a realization of what a monster this was. James Douglas, editor of the Sunday Express, led the attack, arriving immediately at the conclusion that this was an autobiographical narrative. Once it had started there was no limit. They accused him of being a white-slaver, of luring wealthy but aging women to Cefalu and there duping and cheating them. They even cited specific instances—a poor little governess from America, and others. Everything he had ever done they dredged up and re-interpreted.

An incident happened that drove them on ten times harder than before. A young man just out of Oxford, Raoul Loveday, became interested in Crowley’s experiments in the occult and finally went with his wife, Betty May, to Cefalu. There he died, according to the most recent account given by Betty May in her autobiography, of enteric fever brought on from drinking impure water while on a hiking trip. But when the young wife first returned to England she gave out interviews which, reproduced by the Express, conveyed more than an intimation that Crowley had murdered Loveday. One headline said: “New Sinister Revelations of Aleister Crowley. ‘Varsity Lad’s Death. Enticed to Abbey.’ Dreadful Ordeal of a Young Wife. Crowley’s Plans.”

But when the sensational sheet John Bull took up the cry, even this was far exceeded. That paper published a series of articles under the following headlines: “The King of Depravity,” “The Wickedest Man in the World,” “A Cannibal at Large,” “A Man We’d Like to Hang,” “A Human Beast Returns.”

As a result of this campaign, Crowley was forced to leave Italy. He went to Paris but was permitted to remain there only for a short time. Rumors of religious rites in his Paris apartment were taken up by the sensational press in England and the French police requested him to move on. Back in England he was very unhappy, his money gone, his health poor.

But still he was able to travel. In the past two years people have seen him often in Paris. He talked of suicide and one acquaintance reports seeing him walk deliberately into the path of a speeding motor car which missed him only because of the skill of the driver. He may turn up next in Ceylon or Mexico or even in England where mothers still use his name to quiet unruly children—and, incidentally, where many of the leading literary reviews have given him good notices. |