|

SENSATION New York City, New York, U.S.A. January 1940 (pages 32-35)

Astounding Secrets of the Devil Worshippers’ Mystic Love Cult.

Revealing the details of Aleister Crowley’s unholy rites, his power over women, his weird drug orgies and his startling adventures.

Beast or poet?

Monster or moralist?

Genius or madman?

Charlatan or magician?

These are the questions Europe asked for years about Aleister Crowley, one of the most complex characters in the modern world and one of the most extraordinary in human history.

You will read of a man

Who has won fame by sublimely beautiful poetry, yet has committed blasphemies and sacrileges such as the world has never known.

Who has reveled in orgies that astonished Paris, yet has sat motionless for months as a naked yogi, begging his rice under the hot sun of India.

Who steeped himself in opium, yet never became enslaved.

Thus, the second chapter of a series of three, contains more intimate revelations about this astounding character by the writer, who knew and studied Aleister Crowley most closely during his four years in America.

Chapter II

How many women there are throughout the United States, throughout the world, under the influence of Aleister Crowley’s murderous “O.T.O.” cult—some of them may be reading these very lines—who could tell amazing stories if they were willing to speak!

I am thinking at this moment of Leila Waddell, the beautiful violinist and noted concert artist, who was Crowley’s “high priestess” when he was at the height of his fame in England, openly holding elaborate “mystical rites,” attended by many notables—and of the strange circumstances of the talented Leila Waddell in New York.

Aleister Crowley in the ceremonial headdress of his cult.

“What connection has this with the alleged ‘mystical crucifixions’ which you promised to tell about in this chapter?” you may be wondering.

That shall be explained.

In the “Equinox,” which Crowley’s cultists published as part of the “Bible” of the “O.T.O.”, there are many references to “mystical crucifixions” as part of the experiences of initiates and adepts in this cult. To what extent the “crucifixions,” as described in the book, were literal, physical experiences—if at all—I am unable to specify. But before I go further with this account, it is necessary to give you, briefly, some additional light on the character of the strange figure behind it all.

Crowley, whatever else he may be, believes he is a true mystic—perhaps one of the greatest mystics living. Some of his poetry, embalmed in the anthologies, may suffice to give him, after he is dead, at least a minor rank among the immortals. And the various cruelties which I have described—the branding of Lea [Leah Hirsig] on the chest and other incidents—are part and parcel of this side of his character.

One day, in his New York studio, I asked Crowley to tell me something about this alleged practice of “mystical crucifixions.”

“I will tell you,” he said, “the story of a girl whom you may some day meet. But perhaps I’d better read it to you as I have set it down in writing to be included in the ‘Equinox.’ ”

The story Crowley told me was of a modern girl who secretly believed and engaged in “magical” practices, and who had a talisman which she tried to make use of in this way. With a self-sacrificing girl cousin, who was her submissive victim, she went to dreadful lengths to restore to this talisman the potency which she believed it had lost. Here is the essential part of the manuscript from which Crowley read:

“Patricia Fleming ran up the steps into the great house, her thin lips white with rage. For the third time she had failed to bring the man she wanted to her feet. The talisman she had tested had tricked her.

“ ‘What do I need?’ she thought. ‘Must it be blood?’

“She ran, tense and angry, through the house to the chapel. There, she locked the door, struck a secret panel, and came suddenly into a small hidden room. At the end of the room was a scarlet post, and tied to it, her wrists swollen by the whip-lashed that bound her, was a girl, big-boned, strong, and partially unclad.

“She took a hatpin, pierced the love talisman and drove the pin into the girl’s quivering flesh.”

“Patricia held the talisman, which was a piece of vellum, written upon in black. She took a hatpin, pierced the talisman, and drove the pin into the girl’s shoulder.

“ ‘They must have blood,’ she said. ‘Come, don’t wince, dear.’

“Then with her riding whip she struck young Margaret between the shoulders. A shriek rang out. She struck again and again. Great welts of purple stood on the girl’s back; froth tinged with blood came from her mouth, for she had bitten her lips and tongue in agony. Patricia threw the bloody whip into a corner and went down upon her knees. She kissed her cousin, she kissed the talisman.

“She took the talisman and his it in her clothing. Last of all, she loosened the cords, and Margaret sank in a heap on the floor. Patricia threw furs over her; brought wine and poured it down her throat.

“ ‘Sleep now, dear,’ she whispered, and kissed her forehead—”

I broke the silence that followed. “Do you mean to tell me seriously,” I asked Crowley, “that things like that have survived the middle ages?”

“Next week,” said Crowley, with an enigmatic smile, “if you care to meet her, I’ll introduce you to a girl who looks like ‘Patricia.’ She’s coming to America. Wait a minute; I’ll show you her picture.”

From a little iron-bound trunk, he produced a clipping from “The Sketch,” one of London’s leading magazines. It was a portrait of Leila Waddell, the beautiful violinist, and from the text underneath, I judged that Miss Waddell had been a “priestess” of the “O.T.O.” cult while it was at its zenith in England. She was shown clad in a mystical robe, bare-footed, seated upon a throne.

A week later, true to his promise, Crowley took me to see Miss Waddell.

We talked of many things, but I didn’t quite dare to bring up directly such a subject as magic. It seemed utterly impossible that two such cultured, modern persons such as she and Crowley, could have anything in common with the strange beings of whom I had glimpses during my acquaintance with Crowley.

Behind it all there is such a mass of mysteries that lead into old and forgotten cults on one hand, and into events which, on the other are taking place even today in American and English cities, that I doubt if the whole truth will ever be known of Crowley and his strange associates.

Perhaps none of Crowley’s bizarre episodes was more amazing than his so-called “hasheesh orgies.” I was present at a number of them, and I propose to give an accurate account of one which took place in his New York studio. Three others beside myself had been invited to partake of the insidious Oriental drug of the “Arabian Nights” stories—Natazia Fedrovna, a beautiful Russian actress, who had come over from Paris; Ai Nasaki, a Japanese poet; and an Englishman, who had lived for years in the Orient as a member of the diplomatic service. Of course, Lea, “The Dead Soul,” was present.

The big studio had been arranged for the occasion. Three mattresses, covered with heavy Oriental tapestries and piled with cushions, had been laid on the floor alongside the low couch. Crowley was seated at a little table dropping the nauseous, sticky drug into small glasses of sherry to take away the bad taste. Twelve drops constituted a dose, to be repeated every hour or so if the effects were slow in coming.

A half-hour passed. There we lay, in the dimly-lighted, quiet room—and nothing happened. Frankly, I began to be a little bored.

Suddenly, without warning, the drug “got” me. A strange surge like an electric wave seemed to run through my blood and nerves and to sweep me into another world. The ceiling of the room began to shoot up, the walls seemed to recede, and I was in an enormous, well-like hall, in which I was as small as an ant looking at the sky. My mind, racing madly, and completely beyond control, was seizing on every impression that came to my senses, and distorting it.

Where the drug had seized my mind and sent it off into fantastic imaginings, it seemed to have taken hold more directly on the emotions, the physical self of Natasia, the Russian girl. She had stripped off most of her clothing and was dancing alone, in a mad abandon. At first, this seemed very beautiful, but suddenly a horrible thing occurred. Her rounded flesh, as she danced, seemed to be melting away, and then where I had seen a beautiful woman, I saw a hideous thing from the tomb, doing a frightful dance of death. I wanted to shriek, but my throat was contracted.

It was this that turned my hallucinations inward—made me conscious of my own body. I suffered unspeakable tortures. My heart was an enormous hammer, beating with tremendous force. My breathing was like some mighty wind sweeping in and out of my lungs. I thought I was going to die. This passed, and there came visions—some beautiful—some so hideous that they cannot be described. Finally, I went to sleep, in a deep stupor that lasted until the next day.

Mind you, this was just an “experiment” with hasheesh—an experiment which I tried because I wanted to “know”—and which I have never repeated. If anything I have said has given you the slightest inclination to try such a crazy experiment, I want to warn you to desist, to beware of the unspeakable horrors and the dangers of becoming an incurable addict.

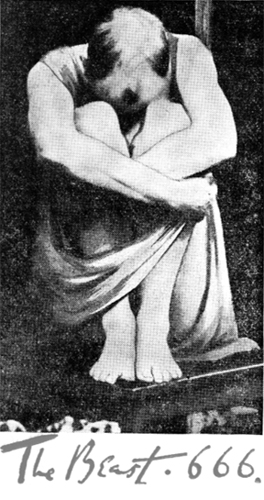

Crowley in one of his trance-like poses and the “Beast” signature with which he ended much of his correspondence.

As for Aleister Crowley, that extraordinary man plunged into these excesses when it pleased him, and shook them off when it pleased him. Less than a month after the experiences of which I have told you, he was camping on Aesopus Island, in the Hudson River, hard and brown as an athlete, painting “Do What Thou Wilt” in enormous red letters over the sides of the rocks, for passengers on river steamers to see.

This was one of Crowley’s maddest episodes. I happen to know that, on quitting Cambridge University, he had a fortune that ran close to a hundred thousand pounds. So far as I know, he hasn’t got a nickel of it left—and most of it has been spent preaching, teaching, writing this “Do What Thou Wilt” doctrine.

I can see him now, with his baggy English knickers, gravely announcing to a circle of Greenwich Villagers that he was going into “magical retirement”—with an old canoe, two moth-eaten blankets and five immense cans of red housepaint as equipment!

No provisions. And not a cent in his pocket. He had spent his last twenty-five dollars on the paint.

“Remember Elijah and the ravens,” he said, with a superb gesture. “Heaven will provide!”

Blasphemy? Or a childish faith? I haven’t the remotest idea. But Providence, or luck, or something, did provide.

It didn’t send Crowley manna, but something much more modern and infinitely better suited to his whim—a pretty Italian countess in riding breeches, who not only supplied food for him in his “magical retirement,” but cooked for him and waited on him like an Oriental slave.

Part of Aesopus Island is farm land, and consequently the farmers of the neighborhood came to it frequently. Crowley landed there at night and when some men arrived the next morning to tend their crops they beheld him, by the water’s edge, garbed in a monk’s coarse black robe, praying to the Sun.

For two days after his arrival at his island camp, Crowley had squatted on a prayer rug in the sunshine reading his mystical books and fasting. But the fasting was carrying holiness too far. So the “prophet” pulled up his belt another notch, got to the mainland and sent a rush telegram “collect” to the pretty little Countess Guerini, who was then in Westchester County, inviting her immediately to visit his “Summer Camp,” and giving her explicit directions how to get there.

The Countess had known Crowley when he was rich, in London. And taking it for granted that she would find cool drinks, servants and bungalows, she came—and got the shock of her life.

The boat which brought her to the island put back to shore immediately. There was Crowley, kneeling on his prayer rug. There was his shabby little tent. And there stood the petite, exquisite Countess.

“What a trick!” she exclaimed. “I shall go straight back to the city tonight.”

“You can’t, my dear,” smiled Crowley; “you can’t get off the island. But do not be afraid. You may have this palatial pavilion for yourself. I shall sleep, or meditate, among the rocks.

The Countess fled into the tent and sobbed herself to sleep.

Why she didn’t leave the next morning? I really don’t know. But she remained. And she was not in love with Crowley, then or at any other time. She was a good soul beneath her frills, and from what I know of women I think she stayed because she discovered that Crowley was hungry—that he hadn’t had anything to eat for three days.

The Countess remained on Aesopus Island nearly two weeks—and people who saw them beheld a situation that you would regard as fantastic and impossible even in a musical comedy.

Statuesque study of Betty May Loveday, famous London art model, who escaped Crowley’s “abbey” after the death of her husband, a mystical poet.

In the mass of contradictions that made up Crowley’s character, there was a streak of something that, for lack of better words, I might describe as pathetic, childlike. It was the thing that made many people, men and women, keep a sincere affection for him despite his dreadful faults.

The very next day she went over to the mainland in a row-boat, and came back with a lot of canned stuff and other food. And Crowley—with a selfishness that was characteristic—now that his stomach was full again, paid not the slightest attention to the young woman who was making this sacrifice.

The Countess, in her riding breeches—which were about the only garments that she had brought fit to be worn in such a place—cooked for him and waited on him as uncomplainingly as if she had been captured in the Arabian desert or bought in the slave market of Samarkand.

“It was the first time I had ever done any work,” she said afterward in New York; “the first time I had ever done anything to help anybody else, and I believe I really like it.”

And so this extraordinary episode ended without scandal. But presently Crowley returned from his “magical retirement” and took his “Do What Thou Wilt” doctrines to Detroit where they made a number of adherents, and where the text of the “secret, sealed ritual” of the cult was made public. I shall tell about it in my next chapter. |