|

EVERYBODY'S WEEKLY London, England 23 April 1949

THE REAL ALEISTER CROWLEY.

By

"He's gone—his soul hath ta'en its eathless flight; Whither? I dread to think—but he is gone." Byron

To many who read in their morning paper, little more than a year ago, that Aleister Crowley was dead, some such thought must have come; and truly there was much of Lord Byron's sinister dramatic hero, Manfred, in the personality of the poet who passed away at Hastings on the first of December, 1947.

In all times of public uneasiness, political unrest, and the menace of perils unknown, the minds of men turn to supernatural aid. The nobler minds find strength and hope in the light of religion, those of a darker mood turn down strange paths led by the will-o'-the-wisps of occult arts. So in our own times many have turned back to follow the somber tracks of half-forgotten lore: theosophies, spiritism, astrology, all have their devotees, and Magic has reappeared in the vocabulary of ordinary people.

A 'Legendary' Figure

To the awakened consciousness of magic is added the persistent clamour of a man's name, which has somehow come to be inseparable from the thought of dark unlawful arts: that name is Aleister Crowley.

It was said years ago of Aleister Crowley that he alone of living men, had created concerning himself a legend, that this extraordinary man had, while living, gathered about himself those attributes of wonder and awe which are associated not with contemporary celebrities, not even with the illustrious personages of history, but with the shadowy figures of remote antiquity.

Crowley effected this marvel, and effected it deliberately. This indeed was "Magick"—(Crowley always wrote the word with a "k.")

Demonic Personage

As the legend of Aleister Crowley grew, as the Myth of Crowley was progressively fostered by Crowley himself, the reputation of the man grew ever worse, until (to ordinary men and women) his name came to be the symbol of evil. Crowley had emerged, as he desired, a demonic personage. Did he not, actually sign his writings with the dread name and number of the Beast of the Apocalypse? Sceptics might sneer and murmur "quack," "charlatan," but they did so with a nervous look over their shoulder; the sinister reputation of the man was potent.

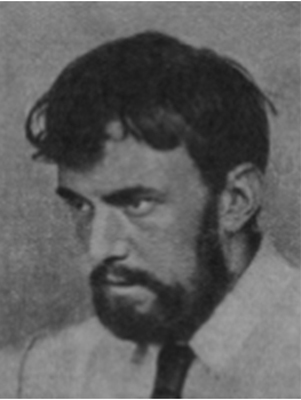

The poet in his prime was Already creating 'a Legend' Concerning himself

During a period of several years I saw A.C. (as his friends styled him) frequently. I came to know him well: better mentally, I believe, than many who knew him longer and, in a sense, more intimately. My association with Crowley was peculiar.

The most of his acquaintances were either his disciples, over whom he exercised an extraordinary power of attraction and command, or curious persons, avid of sensation, who sought his company in the spirit of readers of horror-fictions, seeking unknown terrors to palliate unstrung nerves: for these last he had the most absolute contempt, using them as he pleased, mocking them as they merited.

"I Knew Him Well"

I knew Crowley as one poet, one man of letters, knows another. His life did not touch mine anywhere. With his philosophy, I disagreed. With his poetic canons I was in perfect accord. Our conversations were mutually agreeable, and our horizons were enlarged by exchange of ideas.

Edward Alexander Crowley (such was his baptismal name) was born in 1875. His childhood was tortured by the pitiless government of a guardian, a member of a narrow puritanic sect.

This deplorable atmosphere vitiated the child irrevocably. In his revolt against the terrors of religion, he ran blindfold into the net of diabolism.

His scholarship throve and his genius ripened at Trinity College, Cambridge. He appeared to be a man of destiny. He inherited a splendid fortune; the world lay at his feet. The perversity, which his childhood's sorrows had fostered, might now be exorcised. It was not to be. A great and tragic love was the ruin of Crowley.

To those who would understand (and 'To understand all is to forgive all') the tragedy is manifest in the four great odes which bear the beloved name: 'Rosa Mundi,' 'Rosa Inferni,' 'Rosa Coeli,' 'Rosa Decidua.' Of the last of these wonderful poems a distinguished critic wrote (quoting the poet):

"Truly, 'This is no tragedy of little tears,' but the utterance of a godlike grief."

I'll wait till she is dead, to bring those tears. I doubt not in the garden of my heart Whence she is torn that flowers will bloom again. May those be flowers of weeping, flowers of art, Flowers of great tenderness and pain.

And after all the roar, there steals a strain At last of tuneless infinite pain; And all my being is one throb Of anguish, and one inarticulate sob Catches my throat. All these vain voices die, And all these thunders venomously hurled Stop. My head strikes the floor; one cry, the old cry, Strikes at the sky it exquisite agony: Rose! Rose o' th' World!

Doctrine of 'Will'

Crowley's teaching was founded on Will: "Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the law," was the foundation of sand on which he built the edifice of his philosophy: the phrase he found in Rabelais, and again in the spirit-communications of the famous Elizabethan, Dr. Dee. Crowley amplified the motto: "Love is the Law: Love under Will." But he insisted that by Will, he did not mean Desire. Man's 'true Will' was something very different. Crowley claimed to teach his disciples how to discover their 'true Will.'

It is certain that he believed absolutely in his 'mission.' He was, he said, born a Buddha, with the sign of the sacred swastika on his breast. When Hitler adopted this emblem, he retorted: "Before Hitler was, I am." He was always to his followers the supreme Master, Seer and Prophet. His sincerity in his claim is beyond doubt.

Ceremonial Magic completed Crowley's ruin. To all who have followed that path disaster has come. It led Crowley to the depths. His life-story is a warning to all dabblers in the occult. Financial ruin and bankruptcy followed spiritual ruin. Even his great courage turned to evil. Crowley dared to do things of which other bold men dare not even think.

The Press rejoiced in persecuting him; and the silly persecution followed him to his grave. "Black Mass" was the hue and cry. When I knew Crowley such crazy travesties were not in his thoughts. It was the far older Magic, the ancient Mysteries of Egypt, Persia and Greece which interested him. To his critics he showed a formidable front, standing defiant, like an ogre among pigmies.

Human Foible

One of Crowley's eccentricities was a passion for shocking people. Lord Byron and Sir Richard Burton had the same foible. Crowley could never resist this dangerous urge. He dedicated a volume of riotous drinking songs, which he entitled 'Temperance,' to Lady Astor! When a pompous columnist assailed him in a Sunday paper under the headline, "The Wickedest Man in England" (or was it, "In the World"?), and repeated a rumour that in his dreadful magical rites he sacrificed children, Crowley replied that the writer had overlooked one important point: the children had always to be beautiful and high-born. Crowley loved children and could write of them thus profoundly:

For, mark you! Babes are ware of wiser things, And hold more arcane matters in their mild Cabochon eyes than men are ware of yet. Therefore have poets, lest they should forget, Likened the little sages unto kings.

Smoking his favourite Latakia Tobacco. A later study.

Crowley's powerful intellect was a riddle: now acute in judgment, now nebulous and unbalanced. His erudition, however, was solid and far-reaching, and his genius was prodigious. I have heard an eminent personage, a man famous in arms and letters, one who had known the greatest statesmen, warriors, dictators, of our age, declare solemnly that the most extraordinary genius he ever knew was Crowley.

He could master with astonishing facility any subject which he set himself to study. Of languages ancient and modern he had great store; he was skilled in mathematics, profoundly versed in philosophy, natural and metaphysical. The religions of all races he had pondered and compared. With the doctrines of Kabbalists and Rosicrucians he was familiar. The ancient Mysteries were a favoured field for his speculation.

From such exertions, he found mental repose in the game of chess, at which he excelled, and physical relaxation in daring exploits of mountain and rock climbing. He was a great traveller. Across deserts he had gone to strange Eastern lands, braving unimagined hardships. He had mused alone in the ruined temples of long perished creeds, had invoked the dead and spirit-entities far more potent, in the wilderness; had learned conjuring and wizardry of dervishes, fakirs, and witches; had communed with Brahmins and Buddhist Lamas.

Brilliant Talker

Out of these fountains of experience and learning his conversation flowed to the few privileged to hear him, when the mood inclined him to talk, and the hearer interested him sufficiently to talk to.

Crowley in happy days with his wife [Rose Kelly], the "Rose" of his poems, And his little daughter.

In his lighter moods Crowley's chat sparkled with humourous anecdotes, racy stories, peppered with sallies of the sharpest wit, a wit that seasoned even his deeper talk, as it often does the weightiest passages of his voluminous writings.

A bibliography of Crowley's literary works, now in preparation, lists more than ninety items, published, or printed for private circulation. This list is still incomplete. He left, too, a mass of manuscripts as yet unprinted. Some of his most characteristic writings appeared in "The Equinox," an occult periodical edited by himself, each number of which formed a massive volume.

The books Crowley gave to the world were tastefully and often sumptuously printed. They cover an immense range of subject and thought; but his mystic theories dominate them all, from the renowned treatises on "Magick" and the magnificent odes to novels, short tales and ballads. The riches of his literary achievement lie, however, half-buried under dumps of ribaldry, often gross and sometime blasphemous. Were it not so, those gems of his pens which are prized by connoisseurs would long since have been universally acclaimed.

A Great Poet

He had no sense of propriety, or even common sense, in the publication of his books. His loftiest poems are intermingled with scurrilous doggerel, his loveliest flowers planted among poisonous weeds. More than once did I tell him that his own execrable editing was his chief enemy as an author: he did not contradict me.

Of all Crowley's activities, of all the facets of his genius, his poetry only possesses permanent value; for his scholarship was misapplied. Nothing can exceed the splendour of imagery, the witchery of music, in his highest lyric flights. With awe and pathos, too, they are deeply charged.

They have the qualities of Eastern, rather than of Western poetry: the luxuriance and ambiguity. Were they endowed with more lucidity and purity, and with the reverence for holy things which sacrifices the highest poetry, they might claim that exalted rank.

"Forest of Laurel"

When Crowley, replying to a learned counsel in a notorious lawsuit for libel, which he brought unsuccessfully against a 'Bohemian' authoress, proclaimed in court that he was "the greatest, living English poet," his vaunt was not far from the truth.

Poets there are among his contemporaries who have composed verses as beautiful as Crowley's best, and verses far superior spiritually; but no other poet in our time has conquered thus mightily so vast a realm of poetic theme and meditation. Sweep away the dross; destroy the venomous growth of his unbalanced brain; there will remain about his tomb a forest of laurel.

The poet in his prime was Already creating 'a Legend' Concerning himself.

Amid the self-wrought wreck of his brilliant fortune, amid the failure and degradation of his magical pretentions, he abides, proud and audacious, a poet fired with an imagination, gifted with an eloquence, singular, vehement, and magnificent.

Charles Richard Cammell |