|

CHALK CLIMBING ON BEACHY HEAD

Published in The Scottish Mountaineering Journal Glasgow Scotland May 1895 (Volume 3, Number 17) (pages 288-294)

To the patriotic Scot who regards John o' Groats as not far removed from the centre of things, Beachy Head will appear a very outlandish spot to treat of in the pages of the Journal. Without incurring, therefore, the reproach that qui s'excuse s'accuse, it may be pleaded in justification of this article that the true mountaineer has no domicile; that the chalk of Beachy Head, though some would call it limited in quantity and insignificant in height, will be found to present problems as interesting in their way as any to be found in this country; and that, in spite of its proximity to London, the excellent climbing to be had on this remarkable promontory is almost unknown even to English climbers, and has hitherto been practised, with the assistance of the coast-guard, by the Cockney trippers, whose perils during the summer months form a periodic sensation for the local newspapers.

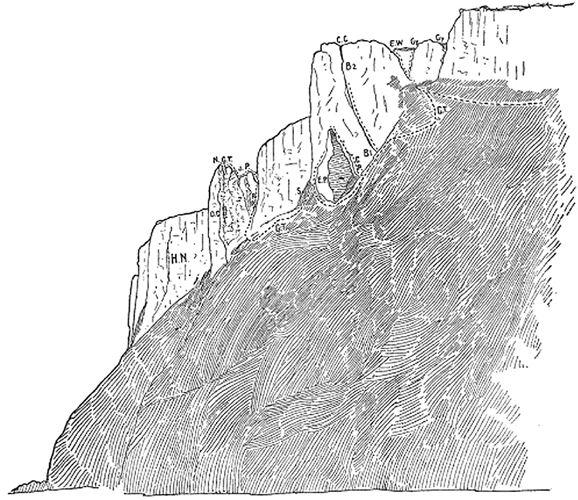

My first visit to the Head took place on the 4th of April in the year of grace 1894, in company with a friend who, considers climbing for climbing's sake as stupid, if not actually sinful. Our object was general exploration, and the part we first hit on was the upper portion of the cliff lying between Monkey island and the Devil's Chimney [D.C.], and to this portion we have since kept. Small as it is, we have not yet exhausted it by one-half. Going down by Monkey Island,[1] we reached a broad, steep, half-grassy ledge called the Grass Traverse [G.T.]. This runs along to the Devil's Chimney, and its upper limit is the vertical cliff. Broad tongues of rotten grass shoot up from the traverse, and the crags above it correspondingly vary in height from 20 to 200 feet.

We passed along this in a westerly direction, and noted the following points of interest in the cliff above. Firstly, a round-topped oblong pillar, which we climbed by the E. and N. Future visitors are recommended to try it by the S. ridge, which would afford a magnificent climb. Secondly, a good many rather shallow gullies. Thirdly, an easy way to the top [E.W.], curtained on its S.W. by a huge buttress of rock. We ran up a grassy slope which hid the lower portion of this formidable obstacle, and a fine sight burst upon our astonished eyes. Behold the entire mass of Etheldreda's pinnacle [E.P.], with the cliff, here fissured with the magnificent "Cuillin crack" [C.C.], some 200 feet high, overhanging it, and the distant sea behind; above, a mass of fleecy clouds framing the picture, and gorgeously lit by the afternoon sun. The effect was superb. We stood for a moment entranced; then in our unpoetical souls practical side of the scene asserted itself.

BEACHY HEAD FROM THE SEA. The slope below the cliff, although shaded dark in this diagram, is composed of dazzingly white chalk, and is only here and there patched with rotten grass.

A cleft a little to the right of the "Cuillin crack" attracted our notice, affording a walk to the top [E.W.]. This cleft forms the top of "Etheldreda's walk," so called, I believe, after a lady who never walked there. It extends downwards and round Etheldreda's pinnacle to the foot of Grant's Chimney.

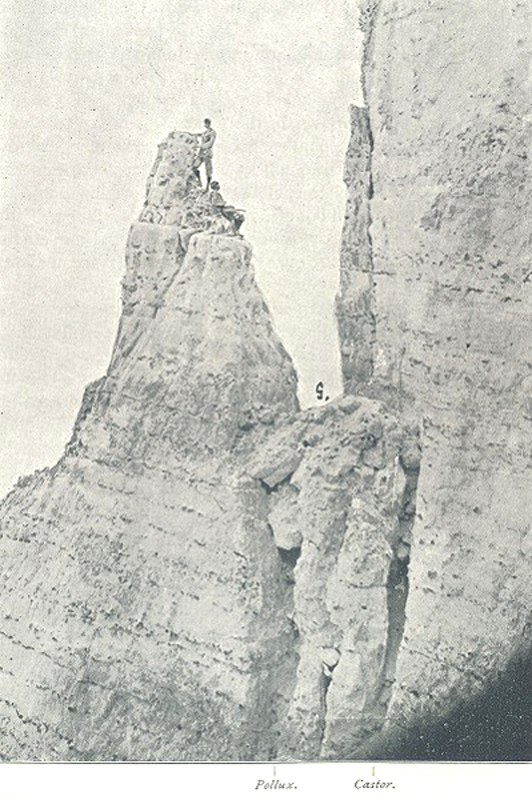

Directly I saw this magnificent pyramid I determined to climb it at once. Two chimneys, side by side, and since named Castor and Pollux [C. & P.], presented the most obvious route to the ridge joining the pinnacle with the mass of the cliff. The north one (Castor) looked easy, and so I determined to try it. The chimney was not then the well-marked gap shown in the illustration, but was almost entirely filled with chalk dust of the consistency of fine flour, caked on the top, and having blocks of various sizes in the middle. All this, at the touch, came down, and the whole weight jammed on my legs, which were well into the chimney. A convulsive series of amoeboid movements enabled me to get out over the débris, when it immediately thundered down, leaving me in a very comfortable gap. I was soon over the jammed stone and on to the ridge. My friend refused to follow, but as he was roped I put on sudden pressure, and he—well—changed his mind. When he reached the ridge I went on for the N. face. This has several natural steps, but the first two yards required a few gentle touches with the magic wand, the chalk being very hard. Thence the route lay westward to the N.W. corner and then back again to the shoulder, only one step being at all awkward. The whole climb, however, requires a method of climbing which may be described as a chemical combination of the writhe, the squirm, and the slither. This indeed applies to all difficult chalk. The rate of motion should never exceed that of a glacier or a South-Eastern express, and a spring or a jerk, it should always be remembered, means a fall. The summit consists of a big square block, which rocked and swayed under me as I sat down, upon it. The return to the ridge was soon accomplished, and I then lowered my friend, and tried to swarm down myself, an operation rendered aggravating by the generous but ill-timed hospitality of the numerous projecting flints.

ETHELDREDA'S PINNACLE, BEACHY HEAD.

G. Grant's chimney.

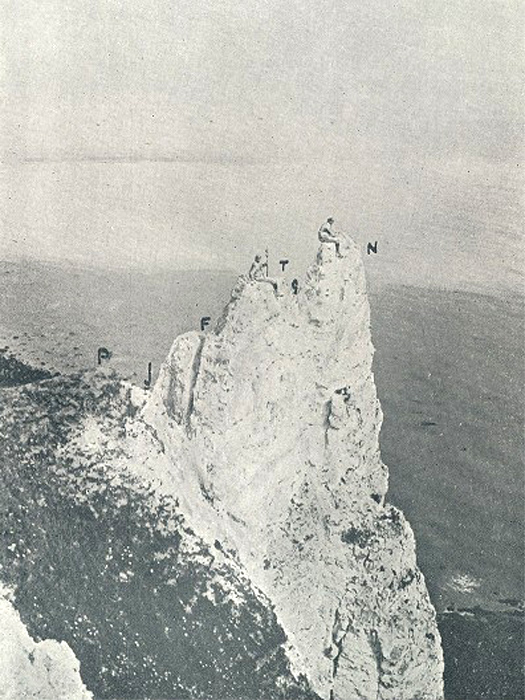

On July 4th we made an attack on the Devil's Chimney, a magnificent pillar of rock which projects boldly from the main cliff at a point rather to the W. of Etheldreda's pinnacle. "Devil's Chimney" is a local name, and, as far as "chimney" goes, misleading to climbers. Nobody, however, who has been twice on the summit, as I have, will entertain the smallest doubt as to its ownership. We walked along the top of the cliffs till we reached the descent to Pisgah, on which my friend fixed himself, while I descended the rotten ridge that leads to Jordan. Above and beyond rises Few-chimney, perhaps 20 feet high, affording what seemed the only possible access to the Tooth. By dint of much squirming, and the judicious use of such pressure holds as were available, I succeeded in reaching the top, to find myself on the top of the block forming the eastern wall of the chimney, while the summit of the Tooth still towered above me in all its rottenness. Both the N. and the E. faces were coated with loose layers of chalk, which came away with a single touch, but the E. had the advantage of being less vertical. After much belabouring of it with my axe I succeeded in reducing it to a condition of comparative stability, and by dint of a few steps and hitching the rope over the top managed to struggle to the summit. The laborious nature of the climbing is evidenced by the fact that two hours and more were required to overcome a vertical height of only thirty feet. After carefully reconnoitring the Needle, which lay beyond, and pronouncing it impossible, I rejoined my friend on Pisgah.

On July 11th I went out to reconnoitre for new climbs, as my cousin, Mr Gregor Grant, intended coming down in the ensuing week to join me. I went down Etheldreda's walk, discovered Grant's Chimney, and proceeded westward till brought up by the tremendous wall of the Devil's Chimney towering some 200 feet above. But the cliff, to my sanguine spirit, seemed practicable, either on the face of the chimney, leading up to the Gash, or on the cliff proper on the right, which would bring me, as I then thought, to Jordan [J]. I now proposed to make the attempt by the latter route. The first obstacle was a smooth hard chalk slope, which needed steps. Once up this the way was easier, but very winding and varied, till a large but unsafe ledge was reached, with a nasty wall rising above and forming the lower part of a knee-shaped buttress, since called the Knee. The chalk here was very rotten, and the flank of the buttress, where the route lay, exceedingly exposed. The difficulties of the way were somehow mastered, and I found myself on another ledge some 50 feet below Pisgah [P]. A very nasty rotten cirque was above me, but, being fairly firm, I could hack away till some moderate hold was obtained. The ascent of this little steep bit brings one under the vertical or undercut cliff. There is here a colossal buttress some 40 feet high, which will probably come down on the next few parties if they hack away too much. A sharp turn to the left brought me to a nice little scree-shoot leading up to Pisgah, and when I flung myself down on its grassy summit I felt exceedingly comforted. The Knee may probably be avoided by a traverse to the left, and the climb will then lead to Jordan; but I have some doubt whether the attempt would not lead one, out of the frying-pan, indeed—but into the fire.

On July 13th, Grant having arrived, we made another attempt upon Etheldreda's pinnacle, and climbed it by a difficult chimney on the opposite side of the cleft from Castor and Pollux. This chimney is 50 feet high, is shaped like a bow, with the concavity facing outwards, and is closed towards the middle by several large jammed stones. The angle above these is not so severe, and another block forms a fine natural arch. Grant took the lead, and, after some arduous climbing, which involved a good. deal of "going outside" at the jammed stones, emerged, victorious on the top. From this col my previous route was followed to the top of the pinnacle, and in descending we made a new variation by way of the Pollux chimney.

THE DEVIL'S CHIMNEY, BEACHY HEAD.

P. Pisgah. J. Jordan. F. Few-chimney. T. Tooth. G. Gash. N. Needle.

After lunch at the Beachy Head Hotel, we followed the usual high-level route to Pisgah, and then proceeded to do the Tooth as before, of course in much less time than on the first ascent. On this Grant "fixed himself" - a humorous term we sometimes employ - and I went down the ridge into the Gash, "fixed myself," and began my steps. The chalk is much firmer than on the Tooth, but the N. face is, if not undercut, at least vertical, the W. overhangs, and the E. is about 70° if not more. On the N.E. corner, therefore, three steps were cut, going as high as possible to save subsequent work. Five times I tried to cross the Gash, but with no decent handhold it is hardly to be expected that one can pull one's self up to a vertical wall. One chance, however, remained. I scooped a hole out in the E. face, inserted my chin, and hauled. I had not shaved for a day or two, so was practically enjoying the advantages of Mummery spikes! The extra steadiness proved sufficient, and I came up into a position of the most ticklish balance conceivable, but the next step was easier, and from it I managed to hitch the rope well over. Soon I was able to get my hands on the ridge; my right leg followed, then the rest of my body, and the Needle was conquered. However, as it is not "built for two," Grant, much to his disappointment, had to stay on the Tooth, and console himself by hoisting the Union Jack, which we left to wave triumphantly over the scene of our victory. For the photographs which illustrate these two climbs I have to thank Mr Sidney Gibbs, who dared the most awful perils in his attempts to depict us.

Later on in the season I returned to Eastbourne with Grant, and prepared for another climb. On October 1st, after Grant had achieved a splendid variation of my climb of the cliff to Pisgah by turning to the right at the cirque instead of the left, and reaching the top by a chimney between the "Split block" and main cliff, we made an unsuccessful attempt upon the "Cuillin crack." This chimney is nearly 200 feet high, and affords the finest and most difficult piece of climbing that I have yet found in the whole neighbourhood. It is broken at two places, one near the bottom, and the other about 100 feet higher up. The first break presents terrible difficulty, but after incredible exertion it yielded, and then I got a leg and an arm jammed, and managed to wriggle up about 60 feet higher. At this point the rope and my strength were alike exhausted, some four hours, without any sort of rest, having already passed. Foothold and handhold there were none that could be relied upon to support Grant's additional weight, if any pressure were to be put on the rope. There was nothing for it but to let down a rope from above, or to descend with ignominy and much toil. So Grant sped away to invoke the assistance of the coastguard, and meanwhile I sat wedged in a most uncomfortable position, at the bottom of the second break, up to which I had struggled while waiting Grant's return. Presently a rope was let down from above, so that by tying my own length of sixty feet to it I could scramble to the top, climbing for the most part, but receiving now and then aid that was more "moral" than any description of it as such. Whoever first climbs the "Cuillin crack" will have no reason to be displeased with his trophy, and will be able to reflect with satisfaction that the superior character of the chalk renders this climb more justifiable than a great many others.

To sum up, climbing on Beachy Head has a place of its own among the fine arts. But let no devotee seek to penetrate the shrine of this spotless deity when she forbids - I mean on wet and windy days. On the former, the soddened chalk is slippery and dangerous, and too unpleasant in fact to be indulged in by the most enthusiastic. Dry windy days, on the other hand, when chalk particles, varying from fine dust to large nuggets, are being driven about, are fatal to the eyes, which may be bloodshot and sore for days afterwards. In external appearance, also, the worshipper must face the infidel fashion of Eastbourne, and be scorned for a miller or a baker; but then, these are small drawbacks to the glorious sensations that await him who is careless of mockers. But the mighty goddess reserves a terrible doom for the profane who would impiously violate her sanctuaries; he will be a foolish man who treats her otherwise than with reverence and respect. Go then, with true worship, undaunted, and your reward shall be joy unspeakable in the glorious divinity of sun-glistening altitude and towering whiteness.

1—I have made countless vain endeavours to discover what Monkey Island may be. Its position is, however, some distance east of Etheldreda's pinnacle. |