|

As Related by John Symonds

from

ALEISTER CROWLEY: THE DEVIL'S CONTEMPLATIVE.

WORLD REVIEW London, England July 1949 (pages 54-57)

I first met Aleister Crowley [on 3 May 1946] when he was already old. He was living in retirement in a boarding-house on the outskirts of Hastings, a large and—to me—sombre house, standing in its own grounds, and hidden from the road by stalwart trees.

A year before, Clifford Bax had said to me: ‘You should meet Aleister Crowley. He will die soon and then you would have lost your chance.’ He added with a smile: ‘I will have him sent to London for you’, as if Aleister Crowley were some fine old vase or piece of carved ivory.

I didn’t bother Mr. Bax to pack up Crowley for me, but instead made the journey to Hastings, taking with me my friend, Rupert Gleadow, the astrologer and poet. ‘He will die soon and then you would have lost your chance,’ I said to him.

I did not think as much of Crowley’s achievements as Arthur Symons had thought of Verlaine’s when, as a young man, he made, in the company of Havelock Ellis, the journey which brought him face to face with the French poet. But I am sure that I felt every bit as keen. Whether I believed in magic or not, or thought Crowley a great poet or just one of the also-rans, I was going to meet a man who had devoted his life to kicking against the pricks, and about whom floated a hundred legends. And although an old man is not necessarily a wise one, the paying of one’s respects to an old poet is homage to all the past.

In addition, I had a personal reason for wishing to meet Crowley: I had been warned with a shudder by a lady in whose house I had lived, when I mentioned that I wanted to meet Aleister Crowley, not to do anything of the kind, for he had put a spell on her husband and it had taken her ten years of prayer to exorcise it.

The moment arrived at last. As he was about to enter the room, I drew back to take the full impact of him.

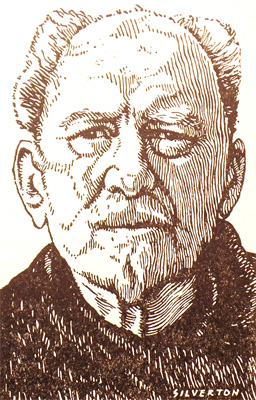

He was not much more than medium height, slightly bent, and shrunk into an old-style plus-four suit with silver buckles at the knee. In his eyes was a staring, puzzled, pained look. He had a little goatee beard and his hair, or what remained of it, was cut close. A large ring was on his finger and a brooch of the god Thoth on his tie.

‘Do what thou wilt, shall be the whole of the law,’ he said in a nasal and fussy tone of voice.

The ‘Wickedest Man in the World’, as Crowley had been called, did look a little wicked, but mostly rather exhausted—whether from wickedness, or from old age, I did not then know.

It was an awkward meeting in rather mediocre circumstances—the drawing-room of the average boarding-house is not, after all, either the most diabolic or the most romantic of surrounding.

I remember that when we began talking about astrology, a subject which Crowley said he hardly believed in. This opinion rather surprised me, in view of the fact that he had been casting horoscopes for himself and others all his life and could more easily tell you what degree and sign of the zodiac the sun was in, than whether the day was Tuesday.

But astrology is a good subject for strangers to get together over, and by the time we had dropped astrology and gone on to magic, we had begun to feel at home.

As lunchtime approached, he kindly ordered lunch for us and retired. He did not eat much now, apart from sweets and sugar (ten spoonfuls in a cup of tea) and drugs. He had a voracious appetite for heroin. Later I was to see him raise a skeleton arm and inject himself with this drug.

‘Do you mind?’

‘Not at all; can I help?’ I replied.

He explained that recently an army officer [Grady McMurtry] had shown such a distasteful face when he had prepared himself for the syringe, that he had gone next door to the bathroom. He added drily: ‘I left the bedroom door open, and from behind the bathroom door I bent down to the keyhole and began to squeal like a stuck pig. When I came out, I found my poor friend had almost fainted.’

Before we left, he gave us each a copy of his Book of the Law, which, he said, was dictated to him in Cairo in 1904 by a spirit called Aiwass. This work is the bible of a new religion for mankind, an orgiastic piece of writing containing two fundamental principles: that there is no law beyond do what thou wilt, and that every man and woman ‘is a star’ or, as Christians would say, has an immortal soul.

I saw Aleister Crowley on a few occasions after this. There was something about him which fascinated me. I cannot define what this ‘something’ was, but its explanation lies in the region where those symbols and archaic pictures cluster—that dark, almost impenetrable part of the mind called by psychologists the Unconscious. He was, after all, a magician, the modern Cagliostro; he had also been considered the devil himself or, at least, a man inspired by the forces of darkness. In his own eyes, he was just a god, one of the company of heaven.

At the end of 1947, Aleister Crowley, as Mr. Bax had predicted, died. The newspapers had found him good copy while he was alive, and they got out their files and rehashed his infamies for their obituaries of England’s famous ‘Black Magician’.

Amongst his papers I came across the strangest of documents: The Magical Record of the Beast 666. The Beast 666 was Crowley, a title he took when he attained the status of Magician. This Magical Record, or diary, is a day-to-day account, set down in the frankest way, of Crowley’s magical, or religious, activities, in which sex and drugs played a not inconsiderable part.

He was, indeed, the strangest of men. I realized how little I had known of him when I had sat beside him in his room in Hastings hung with his own uncanny paintings. Through these pages of his diary he returned in all his mature fascination and eccentric foolhardiness. |