|

ALONG CAME LUND One Magician Rescues the Library of Another

David Meyer

The Caxtonian Journal of the Caxton Club

Volume XXII. No. 1

January 2014 (pages 1-5, 7)

Aleister Crowley (1875-1947) appropriated the number "666." Reference to him as a beast was said to have originated with his unloving mother. He was , to quote the curator of an exhibition on black and white magic at The Peabody Institute Library, "a remarkable Englishman who was a poet, writer, painter, and athlete . . . but best known as a practitioner of devil worship and black magic. His practices were so notorious that he was commonly referred to by his contemporaries as 'The Great Beast' "[1]

Think "crow" to pronounce Crowley's name correctly, although, unlike crows, he was migratory most of his life. He hiked across China; climbed K2, the second-highest mountain in the world (although he didn't reach the summit); spent two years roaming India; had his "first mystical experience" in Stockholm; and became a Thirty-Third Mason in Mexico—all by the time he was 27 years old.

He met Somerset Maugham in Paris in 1904, which led Maugham to write The Magician, a novel that included this passage alluding to Crowley: "There was always something mysterious about him, and he loved to wrap himself in romantic impenetrability. . . . A legend grew up around him, which he fostered sedulously, and it was reported that he had secret vices which could only be whispered in bated breath."

Maugham was writing fiction, but it was based on what he knew of Crowley. In an introduction to a reprint of the novel, Maugham expressed a more critical opinion of Crowley, saying, "I took an immediate dislike to him, but he interested and amused me. . . . He was a fake, but not entirely a fake. . . . He was a liar and unbecomingly boastful, but the odd thing was that he had done some of the things he boasted of. . . . At the time I knew him he was dabbling in Satanism, magic and the occult."[2]

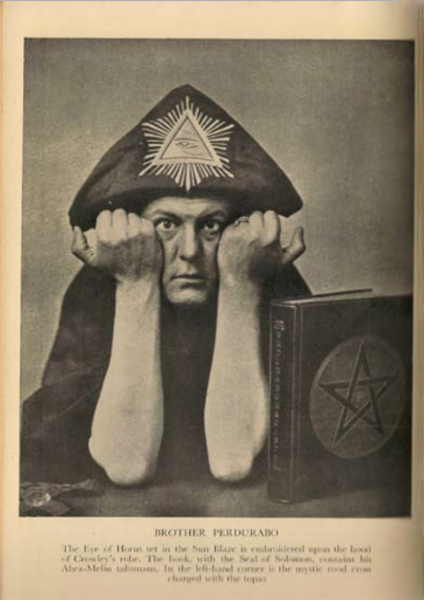

Crowley adorned in regalia for occult pursuits, from The Great Beast: The Life of Aleister Crowley by John Symonds (1952).

Crowley developed a reputation for wreaking havoc on those would-be believers in the mystical and occult who came under his influence. All his life was complicated by associations he formed, secret organizations he joined or created, followers he corrupted and used, wives he seduced and stole.

He had been self-publishing poetry, fiction, erotica, and essays since the late 1890s. Much of this was financed by an inheritance from his parents that was estimated at 40,000 pounds, equivalent to approximately two million dollars at the time. By 1914, however, when he came to the United States, he was reported to be nearly bankrupt. He brought with him personal copies of his manuscripts and books. Titles of a few allude to their contents, such as Alice: an Adultery (1903) and Jezebel and Other Tragic Poems (1898), Other titles suggest more obscure subjects: Aceledama: A Place to Bury Strangers In (1898) and Bagh-i-Muattar: The Scented Garden of Abdullah the Satirist of Shiraz (1910), an erotic novel noted in a Crowley bibliography as having been issued in 200 copies, "the bulk destroyed by H.M. Customs in 1924."[3]

This personal collection, variously described as being carried in two trunks or cases consisted of approximately 125 titles, many the same but in different formats. Ahab and Other Poems, for instance, was privately printed "from a Caxton font of antique type" at London's Chiswick Press in 1903. Crowley brought three copies with him: one (of only two copies) printed on vellum, one (of only 10 copies) printed on Japanese vellum, and one (of 150 copies) printed on handmade paper. He also had the holograph manuscript and the original typed manuscript with corrections in ink and pencil in Crowley's hand—bound in three-quarters leather over marbled boards with raised bands. In fact, most of the typeset works in Crowley's personal library were printed on vellum; these and a number of his manuscripts were luxuriously bound in full leather, some with silk endpapers, by the famous London bindery Zaehnsdorf.

His hope was to sell his so-called "rariora" to John Quinn, a New York attorney, art patron, and book collector. Quinn was known for buying manuscripts from contemporary authors whose work he admired. Quinn came to own the manuscripts and typescript of 24 works by Joseph Conrad, James Joyce's original manuscript of Ulysses, and drafts of works by William Butler Yeats, William Morris, Robert Louis Stevenson, Ezra Pound, and many others.[4] However, his purchases from Crowley were probably disappointing. When Quinn's collection was dispersed, between November 1923 and March 1924, a five-volume auction catalogue was prepared offering 12,108 lots, which were sold in 33 sessions. Of the 67 lots of Crowley books and manuscripts in the sale, only 20 were likely to have been purchased directly from Crowley.[5]

Crowley remained in the United States until 1919, moving from place to place, often staying for only short periods of time to establish contacts with members of a Masonic-related organization variously known as the O.T.O. or Ordo Templi Orientis or Order of the Oriental Templars or Order of the Temple of the East. When the O.T.O. came under Aleister Crowley's leadership its stated beliefs became "Do what thou will shall be the whole of the Law" and "Love is the law, love under will." Free love, purported orgies, and ruined lives and livelihoods were reported in published accounts of the group's activities.

Crowley arrived in Detroit in 1918, bringing his rariora with him. While in New York he had met a prominent Detroit businessman and Mason named Albert W. Ryerson, who agreed to distribute the trade editions of Crowley's many self-published books and to publish his journal, The Equinox. Another reason for Crowley's coming to Detroit was to visit the drug manufacturer Parke-Davis and Company, which was preparing a batch of peyote extract that Crowley intended to use in O.T.O. rituals. Although accounts differ as to why Crowley stored his personal collection in a Detroit warehouse, there it remained, unclaimed, for nearly 40 years.

Robert Lund in the 1990s. (Photo courtesy of Jerry Sharff.)

"Many people leave books in warehouses," Robert Lund said in 1983.

He was being interviewed by Caxtonian Martin Starr, a member of the Illinois Masonic Fraternity who was researching aspects of Crowley's life that had never been adequately explained. Lund, he learned, had purchased Crowley's personal library, and the first question asked was how and when the material was discovered.

"This would have been about 1944 of '56," Lund replied, although he was incorrect regarding the date, which is not surprising considering that he was attempting to recall an event that had occurred 25 years before.

In a letter dated January 13, 1958, Lund wrote his close friend Jay Marshall, a professional magician (and future Caxtonian): "The Crowley stuff is great."

Lund signed the letter, "Robert Lund His number 333 because he is only half as bad as The Great Beast, whose number was 666."

"If they're law books or medical books," Lund continued "you frequently have to pay a trashman to take them away. Not only do they have no value, you actually have to pay someone to take them. . . ." In the process of clearing out books of this kind, workers in the Leonard Warehouse in downtown Detroit "came across some books in beautiful bindings and some manuscript material," Lund said. "The owner of the warehouse was not about to throw this stuff away. He called in a book dealer, who offered him two hundred, two hundred fifty, some such sum. . . . This alarmed the owner, because he had never been offered such an amount of money for some old books. He called the curator of rare books at the Detroit Public Library."

At this point in the interview, Lund and his wife scoured their collective memories to remember the curator's name—Frances Brewer, it was—who told the warehouse owner she'd find out who Aleister Crowley was and call back. When she did, according to Lund, she told the warehouse owner, "The man who is an authority on magicians is a friend of mine. His name is Bob Lund. Why don't you call him?"

Lund began his career as a newspaper reporter in Detroit and later became an auto industry columnist for Hearst Publications. He was also an amateur magician and ardent collector of magic—the performing kind—and sought everything relating to magicians' tricks and careers. "I want it all," he used to say, and he meant it. Over a period of 50 years, through correspondence with magicians and fellow collectors, and by purchases of posters, publicity materials, scrapbooks, periodicals, and books, Lund's collection grew to be one of the largest ever assembled on the subject. Every letter, postcard, news clipping, photograph, and item of ephemera that reached him was kept and carefully filed. The collection became so extensive it filled Lund's home and garage in Southfield, a suburb of Detroit.

"I don't really have an interest in Aleister Crowley," Lund told the warehouse owner and Martin Starr.[6] "I have an interest in all types of superstition, hallucinations, self-deception, that sort of thing." When the warehouse owner called, briefly described the books, and asked Lund if he'd be interested in buying them, Lund recalled telling the man, "It's not really my line, but I know a little bit about Aleister Crowley and I'll make you an offer for them. I made him an offer for what was a great deal of money in those days. 'If you want to pay that sum of money, the books are yours' [the owner said]. I had to go to the bank to borrow that money. It wasn't a great deal of money . . . but it was to me at that time.[7]

"I [made] a complete list of everything I bought. I took a few things I wanted. . . . I gave a few things away. I gave a little thing to Jay Marshall. I can't even remember what it is now,"

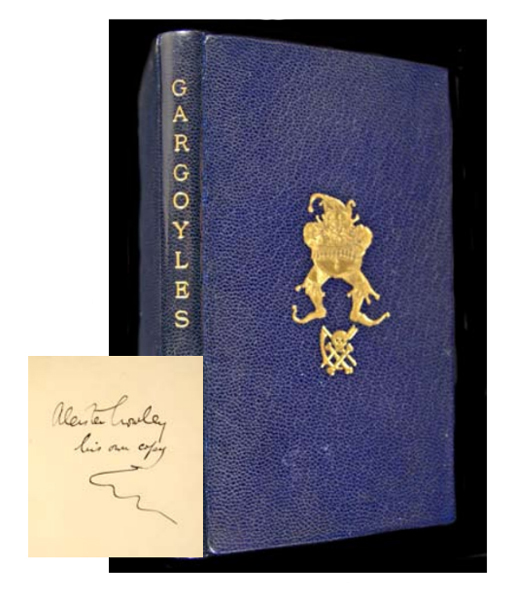

The "little thing" was a book of poems titled Gargoyles: Being Strangely Wrought Images of Life and Death and published in 1906 by the Society for the Propagation of Religious Truth, the name Crowley gave his self-publishing operation. The book was printed on handmade paper in an edition of 50 numbered and signed copies. Crowley's copy, given to Jay, was number "1," signed by the author on the limitation page, and, on the front free endpaper, inscribed "Aleister Crowley his own copy." It was bound by Zaehnsdorf in blue-dyed leather, the title boldly stamped on the spine; and on the cover is a grinning gargoyle and a skull, criss-crossed by bones, a scythe, and an arrow. The poems are powerful: the first lines of the prologue read: "My head is split. The crashing axe / of the agony of things shears through / the stupid skull: out spurt the brains."

Crowley's Gargoyles, a book of poetry, given as a gift to Caxtonian Jay Marshall by Robert Lund. INSET Crowley's inscription on the front free endpaper of Gargoyles.

Twenty-seven poems of similar intensity make up the text. Yet it was the final, untitled, sex-charged poem printed in red ink on the last page that accounted for its going to Jay Marshall. Jay liked poetry of a certain kind—ribald. Crowley's poem addressed to a maiden kneeling before him for a certain purpose was one Lund knew Jay would enjoy.

Another book was given to Lund's friend Joseph Dunninger, a magician and mentalist famous for his radio broadcasts in the 1920s and TV shows in the 1940s and '50s. Lund couldn't recall the title of the book.

"Sometime after I bought this collection," Lund told Martin Starr, "a friend of mine in The Detroit News, a man named Bill Noble, who had written a couple of pieces about my magic collection, called me up and said, 'What's new?' and I told him about finding this Crowley material."

The first of several articles by Noble appeared in the Sunday edition of The Detroit News on January 26, 1958. Four days later, Lund wrote Jay Marshall: "One of the believers called me at home a couple of days ago, after the Crowley piece appeared in the paper, and said I would shortly receive instructions from Crowley's 'magical son' as to how and when I would be required to ship the collection to National Headquarters, in California, under penalty of death if I disobeyed."

Lund appeared to enjoy the threat. "This letter," he wrote to Jay, "will inform my widow that you are to have my autographed copies of [several magic books] in the event of my sudden demise."

Noble's article was titled "Black Magic Once Detroit Cult Decades Ago by Sorcerer Aleister Crowley." A mixture of fact, misstatement, and speculation, it was sensational journalism at its best.[8] Under the heading "Horns of Hair," for example, Noble described an incident of "decades ago" as reported in the Detroit newspapers at the time:

"A unique thing about Crowley," said Lund, "is that he actually believed he was invisible."

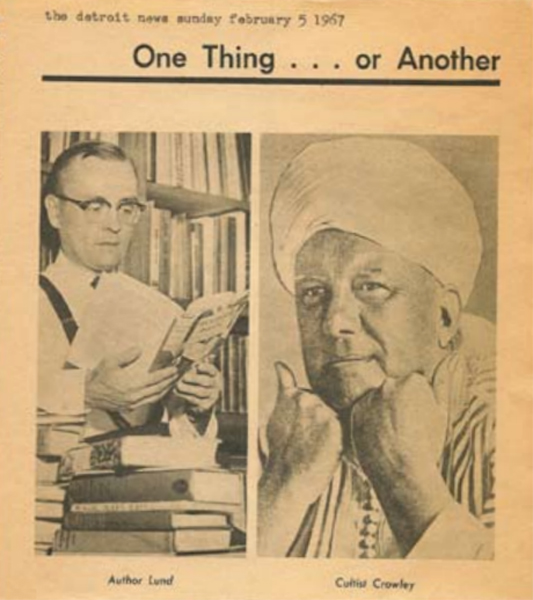

The article produced such a strong reader response that Noble rewrote it nine years later, employing the same information differently worded. When the story appeared in the Sunday edition of February 5, 1967, the title read: "Psychedelic Seeds Planted in 1919?"

Robert Lund and Aleister Crowley, side-by-side in William Noble's article for the Detroit News. This, the follow-up account nine years after Noble's first article, brought "curious phone calls" asking Lund his intentions regarding Crowley's private library.

Talking about the 1958 articles in 1983, Lund said, "As a result . . . I started getting some curious phone calls from people. I got quite a few phone calls from different parts of the United States and some from outside the United States. One man in California . . . Karl Germer told me he was Crowley's son. I said 'What do you mean you're his son?' He says, 'I'm his spiritual son.' I said, 'All right.' "

Karl Germer, a long-time associate of Crowley and member of the O.T.O., wrote two letters to Lund.[9] The first explained how an acquaintance had sent him "the clipping" from The Detroit News and given him Lund's home address. He offered his version of how "Crowley gave to the Leonard Warehouse in Detroit two trunks containing valuable books and manuscripts." In Germer's words, "These two trunks disappeared in a mysterious way—by 'black magic'?"

Germer stated that he had visited Detroit in 1926 but "could not get any useful information from the warehouse people." He also asked Lund for a list of the contents of the trunks, being very specific in his request. "What I need is (a) titles, names, and the type of bindings of the printed books; (b) the same, as far as possible for the MSS." In his second letter, he thanks Lund for allowing him to have "first choice" of the material once he received the list.

Nothing came of this promise, however, as eager inquiries poured in for two months following the appearance of Noble's article: letters from an antiquarian book dealer in Baltimore who had been told about the Crowley material by a friend of Lund's; brief negotiations with Samuel Weiser, the foremost dealer in occult books in the East; calls from those who had read the article or had been alerted to the discovery by the person who had first contacted Germer. One of these eager inquirers was a collector named Philip Kaplan, who lived in Long Island City, New York.

"After I acquired this material," Lund said, "a book dealer that I knew in Detroit named Charlie Boesen, a friend of mine and a very reputable and high-class book dealer, came to me, and he said:

"You want to sell that [Crowley] stuff?'

"Yeah, I'm going to sell it eventually.'

"Well, I'll offer you so much for it.'

"Well, I'll think about it. I'm dealing with a guy named Kaplan who wants to buy it.' "

Lund couldn't recall how Philip Kaplan initially contacted him, but in 1983 he remembered that they'd had phone conversations and Kaplan was "very pleasant." Kaplan, he learned, already owned an extensive collection of Crowley material, including more than 100 photographs of Crowley's paintings and drawings.

In a written account obtained by Martin Starr, Kaplan offered his reasons for believing that Crowley should be considered an important artist and poet. He began on a personal not: "I first became acquainted with Aleister Crowley when I came across the ten volumes of [Crowley's publication] The Equinox . . . in the Cleveland Public Library. This huge work filled with mysticism, occultism, poetry and extraordinary fiction and articles on the most unusual subjects revealed an exciting new personality who was to influence my own creative expressions in the years to come." The combination of Kaplan's enthusiasm for Crowley and his prowess as a fellow collector quite likely influenced Lund's choice in selecting Kaplan as the buyer of Crowley's books and manuscripts. Nut it must not have been a quick decision.

"So Charlie Boesen kept coming back to see me," Lund said. "Every so often . . . and every time he'd increase the price a little bit. I was not twisting his arm because I liked Charlie. I subsequently discovered that Charlie was trying to buy it for a university.

"Now you should understand [this] about me," Lund declared to Martin Starr, "I do not like institutions. I don't like any institution, including this place, which is my own institution."

He was referring to the American Museum of Magic, founded by Lund and his wife in 1976. They conceived the idea of turning his magic collection into a museum, in part to separate it from their home life. They were not successful. Once they made the decision, the project enveloped their lives.

"We created a monster," Lund said many times later. Not only did the museum attract the attention of curious visitors and amateur magicians from around the world, it also became a place where many professional magicians wished to donate their props and publicity materials for posterity. Many others sought out the museum archives for research purposes.

"When I discovered that Charlie was negotiating to buy [the Crowley material] for an institution, I sold it to Me. Kaplan," Lund said. "I sold it . . . for an outrageous sum of money in those days. I sold it to him for less money than Charlie Boesen offered, because I wanted to keep it out of the hands of an institution.[10]

When Martin Starr told Lund that Philip Kaplan sold the Crowley books and manuscripts to the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas in Austin for $17,000, Lund said, "You just caused a great lump in my throat. I sold it for very, very substantially less than $17,000 . . . I sold it for less than $2,000."

The monetary difference was not as substantial as it seemed, considering the fact that Kaplan was selling his entire collection to the university, not just the items he obtained from Lund. More importantly, it was Lund alone who had the greater pleasure of acquiring the long-lost library of Aleister Crowley. He confirms this in a final letter on the subject to Jay Marshall:

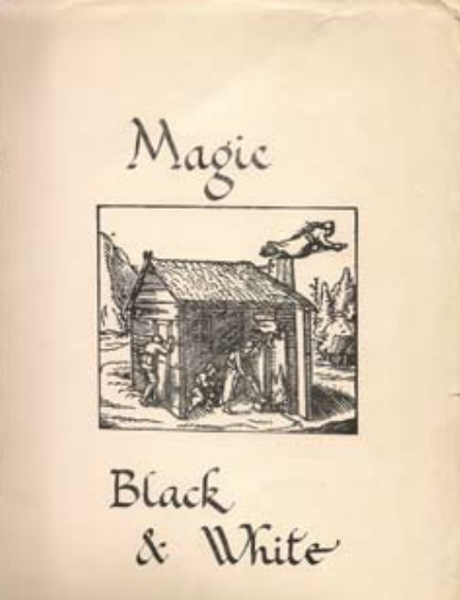

"Magic Black and White"—the exhibition held at Baltimore's Peabody Institute Library in 1960—included items loaned by Robert Lund and Philip Kaplan.[12] For the "Sorcery" section of the show, Kaplan contributed five photographs of Aleister Crowley. One of these was in his role as "Master Therion," one of Crowley's assumed spiritual titles, and another "in magical robes with uraeus serpent crown and magical paraphernalia, including the stele of revealing."

Catalog cover for the "Magic Black and White" exhibition at the Peabody Institute Library, Baltimore, in 1960.

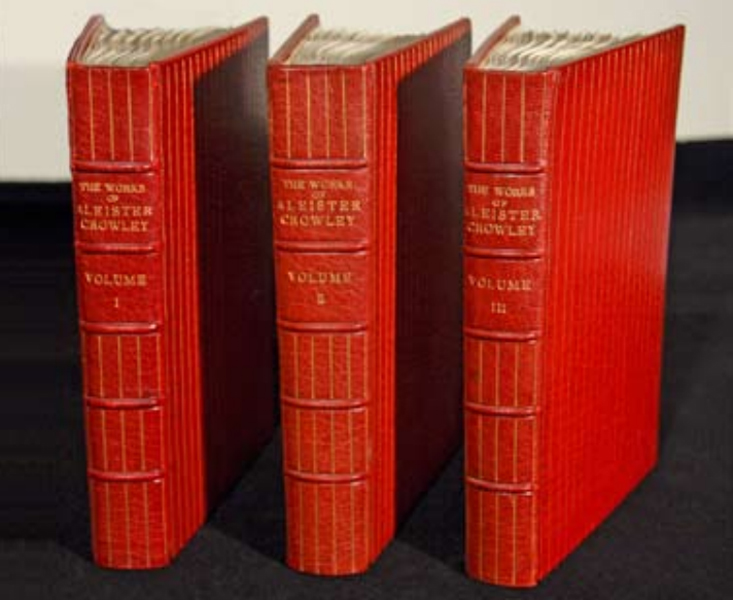

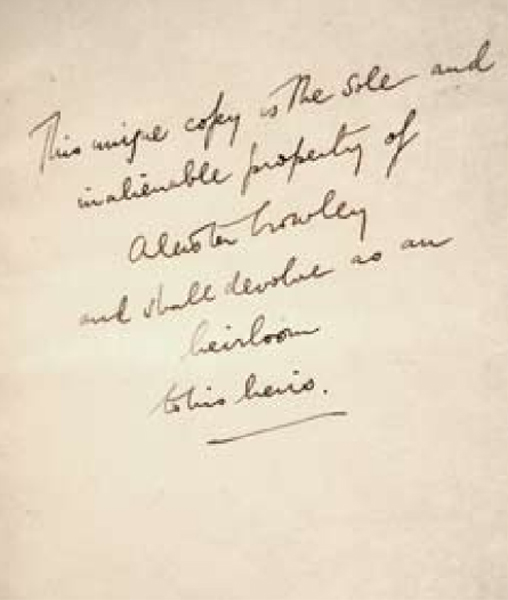

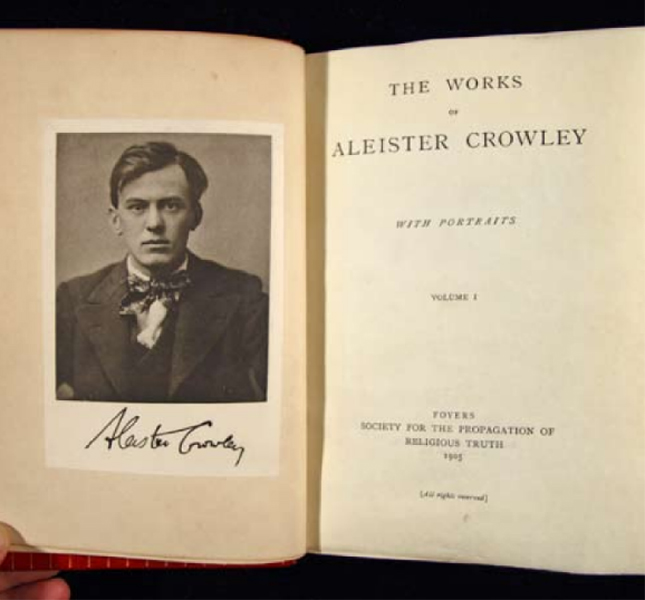

Lund loaned two books that he had not sold to Kaplan: The manuscript of Crowley's Book of Lies (1913) and The Works of Aleister Crowley, a three-volume collection, each volume published individually from 1905 to 1907. The set is printed on vellum and bound in red morocco with gilt stripes running vertically over the front and back covers and spines. Raised bands on the spines set off the titles and volume numbers. On the free front endpaper of the first volume, Crowley had written "This unique copy is the sole and inalienable property of Aleister Crowley and shall devolve as an heirloom to his heirs."

The Works of Aleister Crowley (1905-1907) in three volumes.

Crowley's inscription in The Works of Aleister Crowley.

Many of the individual works reprinted in this three-volume set had been in the library Lund purchased. He may have kept this set as a remembrance of those original manuscripts and first editions he once owned. In the late 1980s, he sold the manuscript of Book of Lies, on my recommendation, to a rare-book dealer in California—"for upwards of money" to use one of Lund's favorite phrases. He kept The Works of Aleister Crowley prominently displayed in an open-front bookcase in his living room.

I had known Bob Lund since the 1960s, when I was a teenage collector of books on magic and would call him to ask for advice. Over the next 35 years, we became good friends and kept in contact by letters, phone calls, and my frequent visits to his home and museum in Marshall. Our conversations covered many topics, but if they strayed too long in any direction, Lund would say, "Let's get back to the subject of magic."

After inspecting his Crowley set in 1986, and seeing that he had tucked a card in it carrying the name and address of the California book dealer I had recommended to him, I sent him a card of my own. I requested that Bob place it nest to the first card. Mine read: "David Meyer will but this Crowley set and pay more for it than any book dealer."

Robert Lund died the night of one of my visits in October 1995. His widow incorporated the American Museum of Magic as a nonprofit institution in 1998. After Elaine's death, I received a call from the attorney handling her estate advising me—for I had forgotten—that I could purchase The Works of Aleister Crowley.

My wife Anita and I drove to Marshall, and on the way back, she said, "Do you realize what day this is? It's June 6, 2006."

666? Not exactly. But perhaps close enough for Karl Germer to believe the date was decreed by black magic.

Title page and Frontispiece portrait of a young Aleister Crowley from the first volume of his collected works.

This article could not have been written without the invaluable research provided by Dorcas Abbott and the generosity of Martin Starr in sharing his interview with Robert Lund. My grateful thanks to both. Thanks also to friends Jim Alfredson, Allen Berlinski, and Daniel Waldron for their assistance in tracking down helpful information; to John Powell for his guidance in the Newberry Library; and to the American Museum of Magic, Inc. for letters written by and to Robert Lund.

Photos of the Gargoyles and Collected Works by Catherine Gass / The Newberry.

NOTES 1—Examples of Crowley's signature—signing as "The Beast", "666 The Beast," and simply "666"—are reproduced in "Panic in Detroit: The Magician and the Motor City" by Richard Kaczynski, Ph.D. Royal Oak, MI: The Blue Equinox Journal, No. 2, Spring 2006. 2—"A Fragment of Autobiography" by W. Somerset Maugham in The Magician. London: William Heinemann Ltd., 1956. 3—"Bibliography of the Works of Aleister Crowley," compiled by Gerald Yorke in The Great Beast: The Life of Aleister Crowley by John Symonds. New York: Roy Publishers, 1952. 4—The Fortunes of Mitchell Kennerly, Bookman by Matthew J. Bruccoli. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Publishers, 1986. 5—This assumption is based on the fact that the chapbook editions were exceptionally limited (for example, "one of a few copies printed"), the printing and binding were luxuriant (two, for example, were bound in "camel's hair wrappers"), and the manuscripts were the author's originals. 6—He has enough of an interest, however, to purchase several biographies, which he read "when I was trying to sell off the Crowley stuff," he wrote to Jay Marshall on May 13, 1958. 7—In a letter to Jay Marshall dated January 20, 1958, Lund stated, "The Crowley stuff broke me for awhile." 8—A veteran newspaper man, Lund often declared, jokingly, "If it appears in the newspaper, it has to be true." 9—Internet articles refer to Germer as the O.H.O., or Outer Head of the Order, of the O.T.O., although one article strongly refutes this titular designation. 10—He had been even more emphatic about this in print 23 years before. In his column "Robert Lund Reports" in the British magic weekly Abra, for January 9, 1960, he wrote that "in another generation the latter day [dealers in old books] will be reduced to selling nothing but those mimeographed sheets that pass as books among magicians because all the good stuff will be stored in institutions. Stop laughing at me, please, because this is a serious matter. You won't believe it, of course, but I am so serious about it that I once sold some stuff to a private collector for $750 less than the University of Indiana offered for it, simply because I did not want the material to rot away in an institution." 11—Letter dated April 12, 1958. 12—Black magic refers to supernatural powers for doing evil, and white magic for doing good. White magic is also associated with deceptions by sleight of hand or illusion. 13—This collection is still in print in hardcover and paperback editions. |