|

THE SPIRIT OF SOLITUDE

An Autohagiography

Subsequently re-Antichristened

THE CONFESSIONS OF ALEISTER CROWLEY

Volume One

London 1929 THE MANDRAKE PRESS 41 Museum Street W.C.1

DEDICATION OF VOLUME ONE

To Three Friends

who suggested this booklet

who gave practical assistance

who saw the point

PRELUDE

CONCERNING THE ART OF BIOGRAPHY, IN GENERAL, AND THE PECULIAR CONSIDERATIONS APPLICABLE TO THE PRESENT ATTEMPT TO PRACTISE THE SAME UPON ALEISTER CROWLEY

“Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law.” Not only to this autohagiography—as he amusedly insists on calling it—of Aleister Crowley, but to every form of biography, biology, even chemistry, these words are key.

“Every man and every woman is a star.” What can we know about a star? By the telescope, a faint phantasm of its optical value. By the spectroscope, a hint of its composition. By the telescope, and our mathematics, its course. In this last case we may legitimately argue from the known to the unknown: by our measure of the brief visible curve, we can calculate whence it has come and whither it will go. Experience justifies our assumptions.

Considerations of this sort are essential to any serious attempt at biography. An infant is not—as our grandmothers thought—an arbitrary jest flung into the world by a cynical deity, to be saved or damned as predestination or freewill required. We know now that “that, that is, is,” as the old hermit of Prague that never saw pen and ink very wittily said to a niece of King Gorboduc.

Nothing can ever be created or destroyed; and therefore the “life” of any individual must be comparable to that brief visible curve, and the object of writing it to divine by the proper measurements the remainder of its career.

The writer of any biography must ask, in the deepest sense, who is he? This questions “who art thou?” is the first which is put to any candidate for initiation. Also, it is the last. What so-and-so is, did and suffered: these are merely clues to that great problem. So then the earliest memories of any autohagiographer will be immensely valuable; their very incoherence will be an infallible guide. For, as Freud has shown, we remember (in the main) what we wish to remember, and forget what is painful. There is thus great danger of deception as to the “facts” of the case; but our memories indicate with uncanny accuracy what is our True Will. And, as above made manifest, it is this True Will which shows the nature of our proper motion.

In writing the life of the average man, there is this fundamental difficulty, that the performance is futile and meaningless, even from the standpoint of the matter-of-fact philosopher; there is, that is to say, no artistic unity. In the case of Aleister Crowley no such Boyg appeared on the hillside; for he himself regards his career as a definitely dramatic composition. It comes to a climax on April 8th, 9th and 10th, 1904 E.V. The slightest incident in the History of the whole universe appears to him as a preparation for that Event; and his subsequent life is merely the aftermath of that crisis.

On the other hand, however, there is the circumstance that his time has been spent in three very distinct manners: the Secret Way of the Initiate, the Path of Poetry and Philosophy, and the Open Sea of Romance and Adventure. It is indeed not unusual to find the first two, or the last two, elements in the molecule of a man: Byron exemplifies this, and Poe that. But it is rare indeed for so strenuous and out-of-doors a life to be associated with such profound devotion to the arts of the quietist; and in this particular instance all three careers are so full that posterity might well be excused for surmising that not one but several individuals were combined in a legend, or even for taking the next step and saying: This Aleister Crowley was not a man, or even a number of men; he is obviously a Solar Myth. Nor could he himself deny such an impeachment too brutally; for already, before he has attained the prime of life, his name is associated with fables not less fantastic than those which have thrown doubt upon the historicity of the Buddha. It should be the True Will of this book to make plain the truth about the man. Yet here again there is a lion in the way. The truth must be falsehood unless it be the whole truth; and the whole truth is partly inaccessible, partly unintelligible, partly incredible and partly unpublishable—that is, in any country where truth in itself is recognized as a dangerous explosive.

A further difficulty is introduced by the nature of the mind, and especially of the memory, of the man himself. We shall come to incidents which show that he is doubtful about clearly remembered circumstances, whether they belong to “eal life” or to dreams, and even that he has utterly forgotten things which no normal man could forget. He has, moreover, so completely overcome the illusion of time (in the sense used by the philosophers, from Lao-Tze and Plotinus to Kant and Whitehead) that he often finds it impossible to disentangle events as a sequence. He has so thoroughly referred phenomena to a single standard that they have lost their individual significance, just as when one has understood the word “cat,” the letters c a t have lost their own value and become mere arbitrary elements of an idea. Further: on reviewing one’s life in perspective the astronomical sequence ceases to be significant. Events rearrange themselves in an order outside time and space, just as in a picture there is no way of distinguishing at what point on the canvas the artist began to paint. Alas! it is impossible to make this a satisfactory book; hurrah! that furnishes the necessary stimulus; it becomes worth while to do it, and by Styx! it shall be done.

O O O O O

It would be absurd to apologise for the form of this book. Excuses are always nauseating. I do not believe for a moment that it would have turned out any better if it had been written in the most favourable circumstances. I mention merely as a matter of general interest the actual difficulties attending the composition.

From the start my position was precarious. I was practically penniless, I had been betrayed in the most shameless and senseless way by practically everyone with whom I was in business relations, I had no means of access to any of the normal conveniences which are considered essential to people engaged in such tasks. On the top of this there sprang up a sudden whirlwind of wanton treachery and brainless persecution, so imbecile yet so violent as to throw even quite sensible people off their base. I ignored this and carried on, but almost immediately both I and one of my principal assistants were stricken down with lingering illness. I carried on. My assistant died1. I carried on. His death was the signal for a fresh outburst of venomous falsehoods. I carried on. The agitation resulted in my being exiled from Italy; through no accusation of any kind was, or could be, alleged against me. That meant that I was torn away from even the most elementary conveniences for writing this book. I carried on. At the moment of writing this paragraph everything in connection with the book is entirely in the air. I am carrying on.

But apart from any of this, I have felt throughout an essential difficulty with regard to the form of the book. The subject is too big to be susceptible of organic structure unless I make a deliberate effort of will and a strict arbitrary selection. It would, as a matter of fact, be easy for me to choose any one of fifty meanings for my life, and illustrate it by carefully chosen facts. Any such method would be open to the criticism which is always ready to devastate any form of idealism. I myself feel that it would be unfair and, what is more, untrue. The alternative has been to make the incidents as full as possible, to state them as they occurred, entirely regardless of any possible bearing upon any possible spiritual significance. This method involves a certain faith in life itself, that it will declare its own meaning and apportion the relative importance of every set of incidents automatically. In other words, it is to assert the theory that the Destiny is a supreme artist, which is notoriously not the case on any accepted definition of art. And yet—a mountain! What a mass of heterogeneous accidents determine its shape! Yet, in the case of a fine mountain, who denies the beauty and even the significance of its form?

In the later years of my life, as I have attained to some understanding of the unity behind the diverse phenomena of experience, and as the natural restriction of elasticity which comes with age has gained ground, it has become progressively easier to group events about a central purpose. But this only means that the principle of selection has been changed. In my early years the actual seasons, climates and occupations determined the sections of my life. My spiritual activities fit into those frames, whereas, more recently, the converse is the case. My physical environment fits into my spiritual preoccupation. This change would be sufficient by itself to ensure the theoretical impossibility of editing a life like mine on any consistent principle.

I find myself obliged, for these and many other reasons, to abandon altogether any idea of conceiving an artistic structure for the work or formulating an artistic purpose. All that I can do is to describe everything that I remember, as best I can, as if it were, in itself, the centre of interest. I must trust nature so to order matters that, in the multiplicity of the material, the proper proportion will somehow appear automatically, just as in the operations of pure chance or inexorable law a unity ennobled by strength and beautified by harmony arises inscrutably out of the chaotic concatenation of circumstances.

At least one claim may be made; nothing has been invented, nothing suppressed, nothing altered and nothing “yellowed up.” I believe that truth is not only stranger than fiction, but more interesting. And I have no motive for deception, because I don't give a damn for the whole human race—“you’re nothing but a pack of cards.”

STANZA I

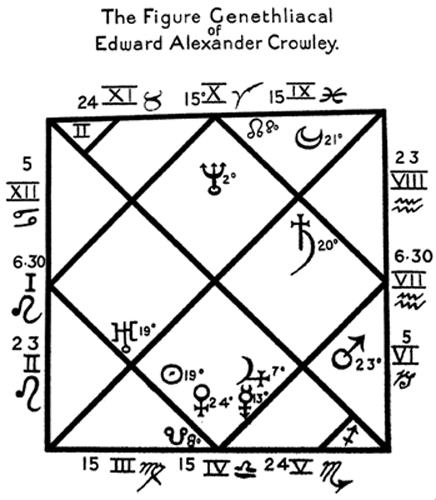

Edward Crowley,1 the wealthy scion of a race of Quakers, was the father of a son born at 30 Clarendon Square, Leamington, Warwichshire,2 on the 12th day of October,3 1875 E.V. between 11 and 12 at night. Leo was just rising at the time, as nearly as can be ascertained.4 The branch of the family of Crowley to which this man belonged has been settled in England since Tudor times: in the days of Bad Queen Bess there was a Bishop Crowley, who wrote epigrams in the style of Marital. One of them—the only one I know—runs thus:

“The bawds of the stews be all turnèd out: But I think they inhabit all England throughout.”

(I cannot find the modern book which quotes this as a footnote and have not been able to trace the original volume.)

The Crowleys, are, however, of Celtic origin; the name O'Crowley is common in south-west Ireland, and the Breton family of de Quérouaille—which gave England a Duchess of Portsmouth—or de Kerval is of the same stock. Legend will have it that the then head of the family came to England with the Earl of Richmond and helped to make him King on Bosworth Field.

Edward Crowley was educated as an engineer, but never practised his profession5. He was devoted to religion and became a follower of John Nelson Darby, the founder of the “Plymouth Brethren”. The fact reveals a stern logician; for the sect is characterized by refusal to compromise; it insists on the literal interpretation of the Bible as the exact words of the Holy Ghost.6

He married (in 1874, one may assume) Emily Bertha Bishop, of a Devon and Somerset family. Her father had died and her brother Tom Bond Bishop had come to London to work in the Civil Service. The important points about the woman are that her schoolmates called her “the little Chinese girl”, that she painted in water-colour with admirable taste destroyed by academic training, and that her powerful natural instincts were suppressed by religion to the point that she became, after her husband's death, a brainless bigot of the most narrow, logical and inhuman type. Yet there was always a struggle; she was really distressed, almost daily, at finding herself obliged by her religion to perform acts of the most senseless atrocity.

Her firstborn son, the aforesaid, was remarkable from the moment of his arrival. He bore on his body the three most important distinguishing marks of a Buddha. He was tongue-tied, and on the second day of his incarnation a surgeon cut the fraenum linguae. He had also the characteristic membrane, which necessitated an operation for phimosis some three lustres later. Lastly, he had upon the centre of his heart four hairs curling from left to right in the exact form of a Swastika7.

He was baptised by the names of Edward Alexander, the latter being the surname of an old friend of this father's, deeply beloved by him for the holiness of his life—by Plymouth Brethren standards, one may suppose. It seems probable that the boy was deeply impressed by being told, at what age (before six) does not appear, that Alexander means “helper of men”. He is still giving himself passionately to the task, despite the intellectual cynicism inseparable from intelligence after one has reached forty.

But the extraordinary fact connected with this baptismal ceremony is this. As the Plymouth Brethren practise infant baptism by immersion, it must have taken place in the first three months of his life. Yet he has a perfectly clear visual recollection of the scene. It took place in a bath-room on the first floor of the house in which he was born. He remembers the shape of the room, the disposal of its appointments, the little group of “brethren” surrounding him, and the surprise of finding himself, dressed in a long white garment, being suddenly dipped and lifted from the water. He has also a clear auditory remembrance of words spoken solemnly over him; though they meant nothing, he was impressed by the peculiar tone. It is not impossible that this gave him an all but unconquerable dislike for the cold plunge, and at the same time a vivid passion for ceremonial speech. These two qualities have played highly important parts in his development.

This baptism, by the way, though it never worried him, provided a peril to the soul of another. When his wife's conduct compelled him to insist upon her divorcing him—a formality as meaningless as their marriage—and she became insane shortly afterward, an eminent masochist named Colonel Gormley, R.A.M.C. (dead previously, then and since) lay in wait for her at the Asylum Gates to marry her. The trouble was that he included among his intellectual lacunae a devotion to the Romish superstition. He feared damnation if he married a divorced dipsomaniac with non-parva-partial dementia. The poor mollusc asked Crowley for details of his baptism. He wrote back that he had been baptised “in the name of the Holy Trinity”.

It now appeared that, had these actual words been used, he was a pagan, his marriage void, Lola Zaza a bastard and his wife a light o'love!

Crowley tried to help the wretched worm; but, alas, he remembered too well the formula: “I baptise thee Edward Alexander in the name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost.” So the gallant colonel had to fork out for a Dispensation from Rome. Crowley himself squandered a lot of cash in one way or another. But he never fell so far as to waste a farthing on the Three-Card trick, or the Three-God trick.

He has also the clearest visualization of some of the people who surrounded him in the first six years of his life, which were spent in Leamington and the neighborhood, which he has never revisited. In particular, there was an orange-coloured old lady named Miss Carey who used to bring him oranges. His first memory of speech is his remark. “Ca'ey, onange”;8 this, however, is remembered because he was told of it later. But he is in full conscious memory of the dining-room of the house, its furniture and pictures, with their arrangement. He also remembers various country walks, one especially through green fields, in which a perambulator figures. The main street of Leamington, and the Leam with its weir—he has loved weirs ever since—Guy's Cliffe at Warwick, and the Castle with its terrace and the white peacocks: all these are as clear as if he had seen them last week. He recalls no other room in the house except his own bedroom, and that only because he “came to himself” one night to find a fire lighted, a steam kettle going, a strange woman present, an atmosphere of anxiety and a feeling of fever; for he had an attack of bronchitis.

He remembers his first governess, Miss Arkell, a grey-haired lady with traces of beard upon her large flat face and a black dress of what he calls bombasine, though to this hour he does not know what bombasine may be, and thinks that the dress was of alpaca or even, it may be of smooth hard silk.

And he remembers the first indication that his mind was of a logical and scientific order.

Ladies will now kindly skip a page, while I lay the facts before a select audience of lawyers, doctors and ministers of religion.

The Misses Cowper consisted of Sister Susan and Sister Emma; the one large, rosy and dry, like an overgrown radish; the other small, pink and moist, rather like Tenniel's Mock Turtle. Both were Plymouth Sister old maids. They were very repulsive to the boy, who has never since liked Calf's head, though partial to similar dishes, or been able to hear the names Susan or Emma without disgust.

One day he said something to his mother which elicited from her the curious anatomical assertion: “Ladies have no legs.” Shortly afterwards, when the Misses Cowper were at dinner with the family, he disappeared from his chair. There must have been some slight commotion on deck, leading to the question of his whereabouts. But at that moment a still small voice came from beneath the table: “Mamma! Mamma! Sister Susan and Sister Emma are not ladies!”

This deduction was perfectly genuine: but in the following incident the cynical may perhaps trace the root of a certain sardonic humour. The child was wont to indicate his views, when silence seemed discretion, by facial gestures. Several people were rash enough to tell him not to make grimaces, as he “might be struck like that”. He would reply, with an air of enlightenment after long meditation: “So that accounts for it.”

All children born into a family whose social and economic conditions are settled are bound to take them for granted as universal. It is only when they meet with incompatible facts that they begin to wonder whether they are suited to their original environment. In this particular case the most trifling incidents of life were necessarily interpreted as part of a prearranged plan, like the beginning of Candide.

The underlying theory of life which was assumed in the household showed itself constantly in practice. It is strange that less than fifty years later, this theory should seem such fantastic folly as to require a detailed account.

The Universe was created by God 4004 B.C. The Bible, authorized version, was literally true, having been dictated by the Holy Ghost himself to scribes incapable of even clerical errors. King James' translators enjoyed an equal immunity. It was considered unusual— and therefore in doubtful taste—to appeal to the original texts. All other versions were regarded as inferior; the Revised Version in particular savoured of heresy. John Nelson Darby, the founder of the Plymouth Brethren, being a very famous biblical scholar, had been invited to sit on the committee and had refused on the ground that some of the other scholars were atheists.

The second coming of the Lord Jesus was confidently expected to occur at any moment.9 So imminent was it that preparations for a distant future—such as signing a lease or insuring one's life—might he held to imply lack of confidence of the promise, “Behold I come quickly.”

A pathetically tragic incident—some years later—illustrates the reality of this absurdity. To modern educated people it must seem unthinkable that so fantastic a superstition could be such a hellish obsession in such recent times and such familiar places.

One fine summer morning, at Redhill, the boy—now eight or nine—got tired of playing by himself in the garden. He came back to the house. It was strangely still and he got frightened. By some odd chance everybody was either out or upstairs. But he jumped to the conclusion that “the Lord had come,” and that he had been “left behind. It was an understood thing that there was no hope for people in this position.” Apart from the Second Advent, it was always possible to be saved up the very moment of death; but once the saints had been called up, the Day of Grace was finally over. Various alarums and excursions would take place as per the Apocalypse, and then would come the millennium, when Satan would be chained for a thousand years and Christ reign for that period over the Jews regathered in Jerusalem. The position of these Jews is not quite clear. They were not saved in the same sense as Christians had been, yet they were not damned. The millennium seems to have been thought of as a fulfilment of god's promise to Abraham; but apparently it had nothing to do with “eternal life”. However, even this modified beatitude as not open to Gentiles who had rejected Christ.

The child was consequently very much relieved by the reappearance of some of the inmates of the house whom he could not imagine as having been lost eternally.

The lot of the saved, even on earth, was painted in the brightest colours. It was held that “all things work together for good to them that love God and are called according to His purpose”. Earthly life was regarded as an ordeal; this was a wicked world and the best thing that could happen to anyone was “to go to be with Christ, which is far better”. On the other hand, the unsaved went to the Lake of Fire and Brimstone which burneth for ever and ever. Edward Crowley used to give away tracts to strangers, besides distributing them by thousands through the post; he was also constantly preaching to vast crowds, all over the country. It was, indeed, the only logical occupation for a humane man who believed that even the noblest and best of mankind were doomed to eternal punishment. One card—a great favourite, as being peculiarly deadly —was headed “Poor Anne's Last Words”; the gist of her remarks appears to have been “Lost, lost, lost!” She had been a servant in the house of Edward Crowley the elder, and her dying delirium had made a deep impression upon the son of the house.

By the way, Edward Crowley possessed the power, as per Higgins, the professor in Bernard Shaw's Pygmalion, of telling instantly from a man's speech what part of the country he lived in. It was his hobby to make walking tours through every part of England, evangelizing in every town and village as he passed. He would engage likely strangers in conversation, diagnose and prescribe for their spiritual diseases, inscribe them in his Address books, and correspond and send religious literature for years. At that time religion was the popular fad in England and few resented his ministrations. His widow continued the sending of tracts, etc. For years after his death.

As a preacher Edward Crowley was magnificently eloquent, speaking as he did from the heart. But, being a gentleman, he could not be a real revivalist, which means manipulating the hysteria of mob-psychology.

1 — “the youngest” (1834-87). 2 — It has been remarked a strange coincidence that one small county should have given England her two greatest poets—for one must not forget Shakespeare (1550-1616). 3 — Presumably this is Nature's compensation for the Horror which blasted Mankind on that date in 1492. 4 — See the Horoscope. 5 — His son elicited this fact by questioning; curious, considering the dates. 6 — On the strength of a text in the book itself: the logic is thus of a peculiar order. 7 — There is a notable tuft of hair upon the forehead, similar to the mound of flesh there situated in the Buddhist legends. And numerous minor marks. 8 — He has never been able to pronounce “R” properly—like a Chinese. 9 — Much was made of the two appearances of “Jesus” after the Ascension. In the first, to Stephen, he was standing, in the second, to Paul, seated, at the right hand of God. Ergo, on the first occasion he was still ready to return at once; on the second, he had made up his mind to let things take their course to the bitter end, as per the Apocalypse. No one saw anything funny, or blasphemous, or even futile, in this doctrine!

STANZA II

If troubles arose in the outer world, they were regarded as the beginning of the fulfilment of the prophecies in Daniel, Matthew and Revelation. But it was understood implicitly that England was specially favoured by God on account of the breach with Rome. The child, who, at this period, was called by the dreadful name Alick, supposed it to be a law of nature that Queen Victoria would never die and that Consols would never go below par.

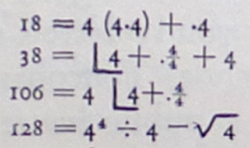

Crowley remembers, as if he had seen it yesterday, the dining-room and the ceremony of family prayers after breakfast. He remembers the order in which the family and the servants sat. A chapter of the Bible was read, each person present taking a verse in turn. At four years old he could read perfectly well. The strange thing about this is not so much his precocity as the fact that he was much less interested in the biblical narratives than in the long Hebrew names. One of his father's favourite sermons was based on the fifth chapter of Genesis; long as the patriarchs lived, they all died in the end. From this he would argue that his hearers would die too; they had therefore better lose no time in making sure of heaven. But the interest of Alick was in the sound of the names themselves — Enoch, Arphaxad, Mahaleel. He often wonders whether this curious trait was symptomatic of his subsequent attainments in poetry, or whether it indicates the attraction which the Hebrew Qabbala was to have for him later on.

With regard to the question of Salvation, by the way, the theory of the exclusive Plymouth Brethren was peculiar, and somewhat trying to a logical mind. They held predestination as rigidly as Calvin, yet this nowise interfered with complete freewill. The crux was faith in Christ, apparently more or less intellectual, but, since “the devils also believe and tremble”, it had to be supplemented by a voluntary acceptance of Christ as one's personal saviour. This being so, the question arose whether Roman Catholics, Anglicans or even Nonconformists could possibly be saved. The general feeling seems to have been that it was impossible for anyone who was once actually saved to be lost, whatever he did.1 But it was, of course, beyond human power to determine whether any given individual had or had not found salvation. This, however, was clear: that any teaching or acceptance of false doctrine must be met by excommunication. The leaders of the Brethren were necessarily profound Theologians. There being no authority of any kind, any brother soever might enunciate any doctrine soever at any time, and this anarchy had already resulted, before the opening of our story, in the division of the Brethren into two great sects: the Open and the Exclusive.

Philip Gosse, the father of Edmund Gosse, was a leader among the Open Brethren, who differed from the Exclusive Brethren, at first, only by tolerating, at the Lord's table, the presence of “Professed Christians” not definitely affiliated to themselves. Edmund Gosse has described his father's attitude in Father and Son. Much of what he wrote taxes the credulity of the reader. Such narrowness and bigotry as that of Philip Gosse seemed beyond belief. Yet Edward Crowley regarded Philip Gosse as likely to be damned for latitudinariansm! No one who loved the Lord Jesus in his heart could be so careless of his Saviour's honour as to “break bread”2 with a man who might be holding unscriptural opinions.

Readers of Father and Son will remember the incident of the Christmas turkey, secretly bought by Mr. Gosse's servants and thrown into the dust-bin by him in the spirit of Moses destroying the Golden Calf. For the Brethren rightly held Christmas to be a Pagan Festival. They sent no Christmas cards and destroyed any that might be sent to them by thoughtless or blaspheming “goats”. Not to disappoint Alick, who liked turkey, the family had that bird for lunch on the 24th and 26th of December. The idea was to “avoid even the appearance of evil”; there was nothing actually wrong in eating turkey on Christmas Day; for Pagan Idols are merely wood and stone — the work of men's hands. But one must not let others suppose that one is complying with heathen customs.

Another early reminiscence. On February 29th, 1808, Alick was taken to see the dead body of his sister, Grace Mary Elizabeth,3 who had only lived five hours. The incident made a curious impression on him. He did not see why he should be disturbed so uselessly. He couldn't do any good; the child was dead; it was none of his business. This attitude continued through his life. He has never attended any funeral4 But that of his father, which he did not mind doing, as he felt himself to be the real centre of interest. But when others have died, though in two cases at least his heart was torn as if by a wild beast, and his life actually blighted for months and years by the catastrophe, he has always turned away from the necrological facts and the customary orgies. It may be that he has a deep-seated innate conviction that the connection of a person with his body is purely symbolic. But there is also the feeling that the fact of death destroys all possible interest; the disaster is irreparable, it should be forgotten as soon as possible. He would not even join the search party after the Kang Chen Janga accident. What object was there in digging frozen corpses from under an avalanche? Dead bodies themselves do not repel him; he is as interested in dissecting rooms as in anything else. When he met the dead body of Consul Litton, he turned back, knowing the man was dead. But when the corpse was brought to Tengyueh, he assisted unflinchingly at the inquiry, because in this instance there was an object in ascertaining the cause of death.

One other group of incidents of early childhood. The family went to the west of England for the summer. Alick remembers Monmouth, or rather Monmouth Castle. It is curious that, in the act of remembering this for the purpose of this book, he was obsessed by the idea that there could not be such a place as Monmouth; the name seemed fantastic. It was confused in his mind with “Monster” and “Mammoth”, and it was some hours before he could convince himself of its reality. He remembers staying in a farm some distance from the road and has a very vague impression of becoming acquainted with such animals as ducks and pigs. Much more clearly arises the vision of himself on a pony with people walking each side. He remembers falling off, starting to yell and being carried up to the house by the frightened governess (or whoever it was) in charge of him. This event had a tragic result. He ought to have been put back on the pony and made to conquer his fears. As it was, he has never been able to feel at home on horseback, though he has ridden thousands of miles, many of them over really dangerous country.

On the other hand — subconscious memory of previous incarnations, or the Eastern soul of him, or the fact that he took to it after he had learned the foolishness of fear? — he was from the first perfectly at home on a camel. And this despite the fact that these animals act like highly placed officials and even — if scabby — like Consuls, and look (when old) like English ladies engaged in good works. (There is much of the vulture in the type of head.)

One incident connected with this journey is of extraordinary interest as throwing a light on future events. Walking with his father in a field, whose general aspect he remembers perfectly well to this day, his attention was called to a clump of nettles and he was warned that they would sting if he touched them. He does not remember what he answered, but whatever it was it elicited from his father the question, “Will you take my word for it or would you rather learn by experience?” He replied, “I would rather learn by experience,” and plunged head foremost into the clump.

This summer was marked by two narrow escapes. He remembers being seated beside the driver of some carriage with what seemed to him an extraordinarily tall box, though this impression may mean merely that he was a very small boy. It was going down hill on a road that curved across a steep slope of very green grass. He remembers the grinding of the brakes. Suddenly his father jumped out of the carriage and cried to the driver that a wheel was coming off. The only trace which this left in later life is that he has always disliked riding in unusual vehicles unless himself in control. He became a reckless cyclist and motorist, but he was nervous for a long while with automobiles unless at the wheel.

The last event of this period occurred at a railway station. He remembers its general appearance and that of the little family group. A porter, staggering under a heavy trunk, slid it suddenly off his back. It missed crushing the boy by a hair's breadth. He does not remember whether he was snatched away, or anything else, except his father's exclamation, “His Guardian Angel was watching over him.” It seems possible that this early impression determined his course in later life when he came to take up Magick; for the one document which gripped him was The Book of the Sacred Magic of Abramelin the Mage, in which the essential work is “To obtain the Knowledge and Conversation of the Holy Guardian Angel”.

It is very important to mention that the mind of the child was almost abnormally normal. He showed no tendency to see visions, as even commonplace children often do. The Bible was his only book at this period; but neither the narrative nor the poetry made any deep impression on him. He was fascinated by the mysteriously prophetic passages, especially those in Revelation. The Christianity in his home was entirely pleasant to him, and yet his sympathies were with the opponents of heaven. He suspects obscurely that this was partly an instinctive love of terrors. The Elders and the harps seemed tame. He preferred the Dragon, the False Prophet, the Beast and the Scarlet Woman, as being more exciting. He revelled in the descriptions of torment. One may suspect, moreover, a strain of congenital masochism. He liked to imagine himself in agony; in particular, he liked to identify himself with the Beast whose number is the number of a man, six hundred and three score six. One can only conjecture that it was the mystery of the number which determined this childish choice.

Many of the memories even of very early childhood seem to be those of a quite adult individual. It is as if the mind and body of the boy were a mere medium being prepared for the expression of a complete soul already in existence. (The word medium is here used in almost exactly the same sense as in spiritualism.) This feeling is very strong; and implies an unshakable conviction that the facts are as suggested above. The explanation can hardly fail to imply the existence of an immanent Spirit (the True Self) which uses incarnations, and possibly many other means, from time to time in order to observe the Universe at a particular point of focus, much as a telescope resolves a nebula.

The congenital masochism of which we have spoken demands further investigation. All his life he has been almost unduly sensitive to pain, physical, mental and moral. There is no perversion in him which makes it enjoyable, yet the phantasy of desiring to be hurt has persisted in his waking imagination, though it never manifests itself in his dreams. It is probable that these peculiarities are connected with certain curious anatomical facts. While his masculinity is above the normal, both physiologically and as witnessed by his powerful growth of beard, he has certain well-marked feminine characteristics. Not only are his limbs as slight and graceful as a girl's but his breasts are developed to quite abnormal degree. There is thus a sort of hermaphroditism in his physical structure; and this is naturally expressed in his mind. But whereas, in most similar cases, the feminine qualities appear at the expense of manhood, in him they are added to a perfectly normal masculine type. The principal effect has been to enable him to understand the psychology of women, to look at any theory with comprehensive and impartial eyes, and to endow him with maternal instincts on spiritual planes. He has thus been able to beat the women he has met at their own game and emerge from the battle of sex triumphant and scatheless. He has been able to philosophize about nature from the standpoint of a complete human being; certain phenomena will always be unintelligible to men as such, others, to women as such. He, by being both at once, has been able to formulate a view of existence which combines the positive and the negative, the active and the passive, in a single identical equation. Finally, intensely as the savage male passion to create has inflamed him, it has been modified by the gentleness and conservatism of womanhood. Again and again, in the course of this history, we shall find his actions determined by this dual structure. Similar types have no doubt existed previously, but none such has been studied. Only in the light of Weininger and Freud5 is it possible to select and interpret the phenomena. The present investigation should be of extraordinary ethical value, for it must be a rare circumstance that a subject with such abnormal qualities so clearly marked should have trained himself to intimate self-analysis and kept an almost daily record of his life and work extending over nearly a quarter of a century.6

1 — “Of those that thou gavest me have I lost not one, except the son of perdition.” In view of predestination, “those” means all the elect and not merely the Eleven, as the unenlightened might suppose. 2 — i.e. sit at the communion-table. 3 — What a name! 4 — With one notable exception, at which he officiated. 5 — That is, for those not initiated into the Magical Tradition and the Holy Qabbala — the Children's table from which Freud and Weininger ate of a few crumbs that fell. 6 — It should be added that the apparently masochistic stigmata disappeared entirely at puberty; their relics are observable only when he is depressed physically. That is, they are wholly symptoms of physiological malaise.

STANZA III

When Alick was about six years old his father moved from Leamington to Redhill, Surrey. There was some reason connected with a gravel soil and country life. The house was called The Grange. It stood in a large long garden ending in woods which overhung the road between Redhill and Merstham; about a mile, perhaps a little more, from Redhill. Alick lived here until 1886 and his memory of this period is of perpetual happiness. He remembers with the utmost clearness innumerable incidents and it becomes hard to select those which possess significance. He was taught by tutors; but they have faded, though their lessons have not. He was very thoroughly grounded in geography, history, Latin and arithmetic. His cousin, Gregor Grant, six years older than himself, was a constant visitor; a somewhat strange indulgence, as Gregor was brought up in Presbyterianism. The lad was very proud of his pedigree. Edward Crowley used to ridicule this, saying, “My family sprang from a gardener who was turned out of the garden for stealing his master's fruit.” Edward Crowley would not allow himself to be addressed as “Esquire” or even “Mr.” It seems a piece of atavism, for a Crowley had petitioned Charles I to take away the family coat of arms; his successor, however, had asked Charles II to restore them, which was done. This is evidence of the Satanic pride of the race. Edward Crowley despised worldly dignities because he was a citizen of Heaven. He would not accept favour or honour from any one less than Jesus Christ.

Alick remembers a lady calling at the house for a subscription in aid of Our Soldiers in Egypt. Edward Crowley browbeat and bullied her into tears with a Philippic on “bibles and brandy”. He was, however, bitterly opposed to the Blue Ribbon Army. He said that abstainers were likely to rely on good works to get to heaven and thus fail to realize their need of Jesus. He preached one Sunday in the town hall, saying, “I would rather preach to a thousand drunkards than a thousand T-totallers.” They retorted by accusing him of being connected with “Crowley's Ales”. He replied that he had been an abstainer for nineteen years, during which he had shares in a brewery. He had now ceased to abstain for some time, but all his money was invested in a waterworks.1

Besides Gregor Grant, Alick's only playmates were the sons of local Brethren. Aristocratic feeling was extremely strong. The usual boyish play-acting, in which various personalities of the moment, such as Sir Garnet Wolseley and Arabi Pasha, were represented, was complicated in practice by a united attack on what were called cads. Alick especially remembers lying in wait at the end of the wood for children on their way to the National School. They had to cross a barrage of arrows and peas and ultimately got so scared that they found a roundabout way.

Facing the drive, across the road, was a sand-pit. Alick remembers jumping from the top with a alpenstock and charging a navvy at work in the pit, knocking him down, and bolting home. But he was not always so courageous. He once transfixed, with the same alpenstock, the bandbox of an errand-boy. The boy, however, was an Italian; and pursued the aggressor to The Grange, when of course the elders intervened. But he remembers being very frightened and tearful because of some connection in his mind between Italians and stabbing. Here again is a curious point of psychology. He has no fear of being struck or cut; but the idea of being pierced disturbs his nerve. He has to pull himself together very vigorously even in the matter of a hypodermic syringe.

There has always been something suggesting the oriental — Chinese or ancient Egyptian — in Alick's personal appearance. As his mother at school had been called “the little Chinese girl”, so his daughter, Lola Zaza, has the Mongolian physiognomy even more pronounced. His thought follows this indication. He has never been able to sympathize with any European religion or philosophy; and of Jewish or Mohammedan thought he has assimilated only the mysticism of the Qabbalists and the Sufis. Even Hindu psychology, thoroughly as he studied it, never satisfied him wholly. As will be seen, Buddhism itself failed to win his devotion. But he found himself instantly at home with the Yi King and the writings of Lao-Tze. Strangely enough, Egyptian symbolism and magical practice made an equal appeal; incompatible as these two systems appear on the surface, the one being atheistic, anarchistic and quietistic, the other theistic, hierarchical and active. Even at this period the East called to him. There is one very significant episode. In some history of the Indian Mutiny was the portrait of Nana Sahib, a proud, fierce, cruel, sensual profile. It was his ideal of beauty. He hated to believe that Nana Sahib had been caught and killed. He wanted to find Nana Sahib, to become his ally, share in torturing prisoners, and yet to suffer at his hands. When Gregor Grant was pretending to be Hyder Ali, and himself Tipu Sahib, he once asked his cousin, “Be cruel to me.”

The influence of Cousin Gregor at this time was paramount. When Gregor was Rob Roy, Alick was Greumoch, the outlaw's henchman in James Grant's novel. The MacGregors appealed to Alick as being the most royal, wronged, romantic, brave and solitary of the clans. There can be no doubt that this phantasy played a great part in determining his passionate admiration of the chief of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, a Hampshire man named Mathers [MacGregor Mathers] who inexplicably claimed to be MacGregor of Glenstrae.

The boy's attitude to his parents is one of the most remarkable facts of his early life. His father was his hero and his friend, though, for some reason or other, there was no real conscious intimacy or understanding. He always disliked and despised his mother. There was a physical repulsion, and an intellectual and social scorn. He treated her almost as a servant. It is perhaps on this account that he remembers practically nothing of her during this period. She always antagonized him. He remembers one Sunday when she found him reading Martin Rattler and scolded him. Edward Crowley took his part. If the book was good enough to read on any day, why not on Sunday? To Edward Crowley, every day was the Lord's Day; Sabbatarianism was Judiasm.

When Alick was eight or thereabouts he was taken by his father to his first school. This was a private school at St. Leonards, kept by an old man named Habershon and his two sons, very strict Evangelicals. Edward Crowley wanted to warn his son against the commonest incident of English school life. He took a very wise way. He read to the boy very impressively the story of Noah's intoxication and its results, concluding: “Never let any one touch you there.” In this way, the injunction was given without arousing morbid curiosity.

Alick remembers little of his life at this school beyond a vivid visual recollection of the playground with its “giant's stride”. He does not remember any of the boys, though the three masters stand out plainly enough. One very extraordinary event remains. In an examination paper, instead of answering some question or other, he pretended to misunderstand it and wrote an answer worthy of James Joyce. Instead of selling a limited edition at an extravagant price, he was soundly birched. Entirely unrepentant, he began to will Old Habershon's death. Strangely enough, this occurred within a few weeks; and he unhesitatingly took the credit to himself.

The boy's intellect was amazingly precocious. It must have been very shortly after the move to Redhill that a tailor named Hemming came from London to make new clothes for his father. Being a “brother”, he was a guest in the house. He offered to teach Alick chess and succeeded only too well, for he lost every game after the first. The boy recalls the method perfectly. It was to catch a developed bishop by attacking it with pawns. (He actually invented the Tarrasch Trap in the Ruy Lopez before he ever read a book on chess.) This wrung from his bewildered teacher the exclamation, “Very judicious with his pawns is your son, Mrs. Crowley!”

As a matter of fact, there must have been more than this in it. Alick had assuredly a special aptitude for the game; for he never met his master till one fatal day in 1895, when W. V. Naish, the President of the C.U.Ch.C., took the “fresher” who had beaten him to Peterhouse, the abode of Mr. H. E. Atkins, since seven times amateur champion of England and still a formidable figure in the Masters' Tournament.

It may here be noted that the injudicious youth tried to trap Atkins with a new move invented by himself. It consists of playing K R B Sq, instead of Castles, in the Muzio Gambit, the idea being to allow White to play P Q 4 in reply to Q B 3.

In 1885 Alick was removed from St. Leonards to a school kept by a Plymouth Brother, an ex-clergyman named H. d'Arcy Champney, M.A. It is a little difficult to explain the boy's psychology at this period. It was probably determined by his admiration for his father, the big, strong, hearty leader of men, who swayed thousands by his eloquence. He sincerely wished to follow in those mighty footsteps and so strove to imitate the great man as best he might. Accordingly, he aimed at being the most devoted follower of Jesus in the school. He was not hypocritical in any sense.

All this strikes one as absolutely natural; what is extraordinary is the sequel.

A letter dating from his early school life at Cambridge:

He was thoroughly happy at this school; the boys liked and admired him; he made remarkable progress in his studies and was very proud of his first prize, White's Selborne, for coming out top in “Religious Knowledge, Classics and French”.

But to this day he has never read the book! For certain lines of study he had a profound, instinctive and ineradicable aversion. Natural History, in any form, is one of these. It is hard to suggest a reason. Did he dislike to analyse beauty? Did he feel that certain subjects were unimportant, led to nothing that he wanted to explore? However this may be, he used to make up his mind with absolute finality as to whether he would or would not take some particular course. If he would, be panted after it like the hart after the water-brooks; if no, nothing would persuade him to waste an hour on it.

It was while he was at this school that he began to write poetry. He had read none, except “Casabianca”, “Excelsior”, the doggerel of Sir Walter Scott and such trash. But he had a genuine love for the simple Hymns for the little Flock compiled by the “Brethren”. His first taste of real poetry was Lycidas, set for the Cambridge Local Examination, if his memory serves him aright. He fell in love with it at once and had it by heart in a few days. But his own earliest effort is more on the lines of the hymnal. Only a few lines remain.

I Terror, and darkness, and horrid despair! Agony painted upon the once fair Brow of the man who refused to give up The love of the wine-filled, the o'erflowing cup. “Wine is a mocker, strong drink is raging.” No wine in death is his torment assuaging.

II . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Just what the parson had told me when young: Just what the people in chapel have sung: “Wine is a mocker, strong drink is raging.” . . . . . . . . .

Of this Redhill period there remain also memories of two summers, one in France and Switzerland, the other in the Highlands.

The former has left numerous traces, chiefly of a visual character; the Grand Hotel in Paris, Lucerne and the Lion, William Tell, the Bears at Berne, the Rigi, the Staubbach, Trummelbach and Giessbach, Basle and the Rhine, the Dance of Death. Two points only concern us: he objected violently to being taken out in the cold morning to see the sunrise from a platform on the Rigi-Kulm and to illumination of a waterfall by coloured lights. He felt acutely that nature should be allowed to go her own way and he his! There was plenty of beauty in the world; why make oneself uncomfortable in order to see an extra? Also, you can't improve a waterfall by stage-craft!

There is the skeleton of quite a philosophy of life in this.

As to the Scottish Highlands, the boy's mind had been so poisoned by romance that he saw nothing that he can remember. The scenery was merely a setting for silly daydreams of Roderick Dhu!

Three other episodes of the Redhill period are pertinent; not that they are in themselves very significant, save that two of them exhibit Alick in the character of a normally mischievous boy with some skill in playing upon other people's psychology. But they illustrate the singular environment.

A frequent guest at The Grange was an old gentleman named Sherrall, whose vice was Castor Oil. Edward Crowley was in the habit of holding “Tea Meetings”; a score or so of people would be invited to what is vulgarly known as a blow-out, and when the physical animal was satisfied, there would be a debauch of spiritual edification. On the mahogany table in the dining-room, extended to its fullest length, would stand two silver urns of tea. Into one of these young Alick emptied Mr. Sherrall's Caster Oil. So far, so good. The point is this, that the people served from that urn were too polite or over-awed either to call the attention of their hostess or to abstain from the accursed beverage. The only precaution necessary was to prevent that lady herself from seeing one of the doctored cups.

A rather similar jest was played at a prayer meeting at the house of a Brother named Nunnerley. Refreshment was offered before the meeting; and a Sister, named Mrs. Musty, had been marked down on account of her notorious greed. Alick and some fellow conspirators kept on plying her with food after every one else had finished, with the object of delaying the prayer meeting. The women herself was too stupid to see what was happening and the Brethren could not be rude enough even to hint their feelings.

This hesitation to act with authority, which was part of the general theoretical P.B. objection to priestcraft, on one occasion reached an astounding point in the following circumstances. A Mr. Clapham, the odour of whose beard proclaimed him truthfully a fishmonger, had a wife and a daughter who was engaged to a Mr. Munday. These three had gone on an excursion to Boulogne; and, by accident or design, the engaged couple missed the boat for Folkestone. It was again a question of avoiding even the appearance of evil and Mrs. Clapham was expelled from fellowship. It is to be presumed that her husband believed her innocent of all complicity, as à priori appears the most natural hypothesis. In any case, next Sunday morning she took her place with her husband at the Lord's Table. It is almost inconceivable that any gathering of human beings, united to celebrate the supreme sacrament of their creed, should have been destitute of any means of safeguarding common decency. But the fear of the priest was paramount; and the entire meeting waited and fidgeted for over an hour in embarrassed silence. Ultimately, a baker named Banfield got up trembling in inquired timorously: “May I ask Mr. Clapham if it is Mrs. Clapham's intention to break bread this morning” Mrs. Clapham then bounced out of the room and slammed the door, after which the meeting proceeded as usual.

Bourbonism still survives among some people in England. I remember explaining some action of mine to Gerald Kelly as taken on my lawyer's advice. He answered contemptuously, “Lawyers are servants!” The social position of the Lord Chancellor and other legal officers of the Crown meant no more to him than the preponderance of lawyers on the councils of the nation. He stuck to the futile stupidity that any man who used his brains to earn a living was an inferior. This is an extreme case of an exceptionally stupid standpoint, but the psychological root of the attitude permeates English conceptions. The definition of self-respect contains a clause to include pitiless contempt for some other class. In my childhood, Mrs. Clapham — one of whose adventures has been already recorded — once came to the grain in conjugal infelicity. “How could I ever love that man?” she exclaimed; “why, he takes his salt with his knife!” There is nothing to warn a fishmonger's wife that such sublime devotion to etiquette is in any way ridiculous. English society is impregnated from top to bottom with this spirit. The supreme satisfaction is to be able to despise one's neighbour and this fact goes far to account for religious intolerance. It is evidently consoling to reflect that the people next door are headed for hell.

Practically all boys are born with the aristocratic spirit.4 In most cases they are broken down, partly by bullying, partly by experience. In the case of Alick, he was the only son of a father who was naturally a leader of men. In him, therefore, this spirit grew unchecked. He knew no superior but his father; and though that father ostentatiously avoided assuming authority over the other Brethren, it was, of course, none the less there. The boy seems to have despised from the first the absence of hierarchy among the Brethren, though at the same time they formed the most exclusive body on earth, being the only people that were going to heaven. There is thus an extreme psychological contradiction inherent in the situation. It is improbable that Alick was aware at the time of the real feelings which must have been implanted in him by this environment; but the main result was undoubtedly to stimulate his pride and ambition in a most unwholesome (?) degree. His social and financial position, the obvious envy of his associates, his undoubted personal prowess, physical and intellectual, all combined to make it impossible for him to be satisfied to take any place in the world but the top. The Plymouth Brethren refused to take any part in politics. Among them, the peer and the peasant met theoretically as equals, so that the social system of England was simply ignored. The boy could not aspire to become prime minister or even king; he was already apart from and beyond all that. It will be seen that as soon as he arrived at an age where ambitions are compelled to assume concrete form, his position became extremely difficult. The earth was not big enough to hold him.

In looking back over his life up to May 1886, he can find little consecution and practically no coherence in his recollections. But from that month onwards there is change. It is as if the event which occurred at that time created a new faculty in his mind. A new factor had arisen and its name was Death. He was called home from school in the middle of the term to attend a special prayer meeting at Redhill. His father had been taken ill. The local doctor had sent him to see Sir James Paget, who had advised an immediate operation for cancer of the tongue. Brethren from far and near had been summoned to help discover the Lord's will in the matter. The upshot was that the operation was declined; it was decided to treat the disease by Count Mattei's Electro-Homeopathy, a now discarded system of unusually outrageous quackery. No doctor addicted to this form of swindling being locally available, The Grange was given up and a house called Glenburnie taken at Southampton.

On March 5th, 1887, Edward Crowley died. The course of the disease had been practically painless. Only one point is of interest to our present purpose. On the night of March 5th, the boy — away at school — dreamed that his father was dead. There was no reason for this in the ordinary way, as the reports had been highly optimistic. The boy remembers that the quality of the dream was entirely different from anything that he had known. The news of the death did not arrive in Cambridge till the following morning. The interest of this fact depends on a subsequent parallel. During the years that followed, the boy — and the man — dreamed repeatedly that his mother was dead; but on the day of her death he — then 3,000 miles away — had the same dream, save that it differed from the others by possessing this peculiar indescribable but unmistakable quality that he remembered in connection with the death of his father.

From the moment of the funeral the boy's life entered on an entirely new phase. The change was radical. Within three weeks of his return to school he got into trouble for the first time. He does not remember for what offence,5 but only that his punishment was diminished on account of his bereavement. This was the first symptom of a complete reversal of his attitude to life in every respect. It seems obvious that his father's death must have been causally connected with it. But even so, the events remain inexplicable. The conditions of his school life, for instance, can hardly have altered, yet his reaction to them makes it almost incredible that it was the same boy.

Previous to the death of Edward Crowley, the recollections of his son, however vivid or detailed, appear to him strangely impersonal. In throwing back his mind to that period, he feels, although attention constantly elicits new facts, that he is investigating the behavior of somebody else. It is only from this point that he begins to think of himself in the first person. From this point, however, he does so; and is able to continue this autohagiography in a more conventional style by speaking of himself as “I”.

1 — At Amsterdam. It was a failure at first, the natives objecting to a liquid which lacked taste, smell and colour. 2 — i.e. Of the “playground”. 3 — Query? “Oiler”, of course, but what was that doing? 4 — It is purely a question of virility: compare the noble races, Arabs, Pathans, Ghurkas, Japanese, etc. with the “moral” races. Of course, absence of caste determines loss of virility and vice versa. 5 — On revision, he thinks it was “talking on the march”, a whispered word to the other half of his scale of the “crocodile”.

STANZA IV

I had naturally no idea at the time that the death of my father would make any practical difference to my environment. In most similar cases it probably would not have done so. Most widows naturally remain in the groove.

As things were, I found myself in a totally new environment. My father's religious opinions had tended to alienate him from his family: and the friends whom he had made in his own circle had no interest in visiting my mother. I was thrown into the atmosphere of her family. She moved to London in order to be near her brother, whom till then I had hardly met.

Tom Bond Bishop was a prominent figure in religious and philanthropic circles in London. He held a more or less important position in the Custom House, but had no ambitions connected with the Civil Service. He devoted the whole of this spare time and energy to the propagation of the extraordinarily narrow, ignorant and bigoted Evangelicalism in which he believed. He had founded the Children's Scripture Union and the Children's Special Service Mission. The former dictates to children what passages of the Bible they shall read daily: the latter drags them from their play at the seaside and hands them over to the ravings of pious undergraduates or hired gospel-geysers. Within his limits, he was a man of acute intelligence and great executive and organizing ability. A Manning plus bigoted sincerity; a Cotton Mather minus imagination; one might even say a Paul deprived of logical ability, and this defect supplied by invulnerable cocksureness. He was inaccessible to doubt; he knew that he was right on every point.

I once put it to him: suppose a climber roped to another who has fallen. He cannot save him and must fall also unless he cut the rope. What should he do? My uncle replied, “God would never allow a man to be placed in such a position”! ! ! ! This unreason made him mentally and morally lower than the cattle of the fields. He obeyed blind savage impulses and took them for the sanctions of the Almighty.

“To the lachrymal glands of a crocodile he added the bowels of compassion of a cast-iron rhinoceros; with the meanness and cruelty of a eunuch he combined the calculating avarice of a Scotch Jew, without the whisky of the one or the sympathetic imagination of the other. Perfidious and hypocritical as the Jesuit of Protestant fable, he was unctuous as Uriah Heep, and for the rest possessed the vices of Joseph Surface and Tartuffe; yet, being without the human weaknesses which make them possible, he was a more virtuous, and therefore a more odious, villain.

“In feature resembling a shaven ape, in figure a dislocated Dachshund, his personal appearance was at the first glance unattractive. But the clothes made by a City tailor lent such general harmony to the whole as to reconcile the observer to the phenomenon observed.

“Of unrivalled cunning, his address was plausible; he concealed his genius under a mask of matchless mediocrity and his intellectual force under the cloak of piety. In religion he was an Evangelical, that type of Nonconformist who remains in the Church in the hope of capturing its organization and its revenues.

“An associate of such creatures of an inscrutable Providence as Coote and Torrey, he surpassed the one in sanctimoniousness, the other in bigotry, though he always thought blackmail too risky and slander a tactical error.1

No more cruel fanatic, no meaner villain, ever walked this earth. My father, wrong-headed as he was, had humanity and a certain degree of common-sense; he had a logical mind and never confused spiritual with material issues. He could never have believed, like my uncle, that the cut and colour of “Sunday clothes” could be a matter of importance to the Deity. Having decided that faith and not works was essential to salvation, he could not attach any vital importance to works. With him, the reason for refraining from sin was simply that it showed ingratitude to the Saviour. In the case of the sinner, it was almost a hopeful sign that he should sin thoroughly. He was more likely to reach that conviction of sin which would show him his need of salvation. The material punishment of sin (again) was likely to bring him to his knees. Good works in the sinner were worthless. “All our righteousness is as filthy rags.” It was the Devil's favourite trick to induce people to rely on their good character. The parable of the Pharisee and the Publican taught this clearly enough.

I do not know whether my Uncle Tom could have found any arguments against this theory, but in practice he had a horror of what he called sin which was exaggerated almost to the point of insanity. His talents, I may almost say his genius,2 gave him tremendous influence. In his own house he was a ruthless, petty tyrant; and it was into this den of bitter slavery that I was suddenly hurled from my position of fresh air, freedom and heirship.

He lived in London, in what was then called Thistle Grove. The name has since been changed to Drayton Gardens, despite a petition enthusiastically supported by Bishop; the objection was that a public house in the neighbourhood was called the Drayton Arms. This is typical of my uncle's attitude to life. His sense of Humour. When I called him “Uncle”, he would snigger, “Oh my prophetic soul, my uncle!” But the time came when I knew most of Hamlet by heart, and when he next shot off his “joke”, I continued the quotation, replying sternly, “Ay, that incestuous, that adulterate beast!” — I am, in a way, glad to think that at the end of his long and obscene life I was reconciled with him. The very last letter he ever received from me admitted (if a little grudgingly) that his mind was so distorted that he had really no idea how vile a thing he was. I think this must have stirred his sense of shame. At least, I never received any answer.

I suppose that the household at Thistle Grove was as representative of one part of England as could possibly have been imagined. It was nondescript. It was neither upper nor lower middle-class. It had not sufficient individuality even to belong to a category. My grandmother was a particularly charming old lady. She was inexpressibly dignified in her black silks and her lace cap. She had been imported from the country by the exigencies of her son's position in the Civil Service. She was extremely lovable; I never remember hearing a cross word fall from her. She was addicted to the infamous vice of Bezique. It was, of course, impossible to have “The Devil's Picture Books” in a house frequented by the leading lights of Evangelicalism. But my Aunt Ada had painted a pack of cards in which the suits were roses, violets, etc. It was the same game; but the camouflage satisfied my uncle's conscience. No Pharisee ever scoured the outside of the cup and platter more assiduously than he.

My grandmother was the second wife of her husband; of the first marriage there were two surviving children; Anne, a stout and sensual old maid, who always filled me with intense physical repulsion; she was shiny and greasy with a blob nose and thick wet lips. Every night she tucked a bottle of stout under her arm and took it to bed with her — adding this invariable “joke” — “My baby!” Even to-day, when people happen to drink stout at a table where I am sitting, I manage instinctively not to see it.

Her brother John had lived for many years in Australia in enjoyment of wealth and civic distinction. His wealth failed when his health broke; and he returned to England to live with the family. He was a typical hardy out-door man with all the Colonial freedom of thought, speech and manner. He found himself in the power of his half-brother's acrid code. He had to smoke his pipe by stealth and he was bullied about his soul until his mind gave way. At family prayers he was perpetually being prayed at; his personality being carefully described lest the Lord should mistake his identity. The description would have suited the average murderer as observed by a singularly uncharitable pacifist.

I am particularly proud of myself for the way I behaved to him. It was impossible to help liking the simple-minded genial soul of the man. I remember one day at Streatham, after he and my grandmother had come to live with us, that I tried to cheer him up. Shaking all over, he explained to me almost in tears that he was afraid he was “not all right with Christ.” I look back almost with incredulity upon myself. It was not I that spoke; I answered him with brusque authority, though I was a peculiarly shy boy not yet sixteen. I told him plainly that the whole thing was nonsense, that Christ was a fable, that there was no such thing as sin, and that he ought to thank his stars that he had lived his whole life away from the hypocritical crew of trembling slaves who believed in such nonsense. Already my Unconscious Self was singing in my ears that terrific climax of Browning's Renan-chorus:

“Oh, dread succession to a dizzy post! Sad sway of sceptre whose mere touch appals! Ghastly dethronement, cursed by those the most On whose repugnant brow the crown next falls!”

However, he became melancholy-mad; and died in that condition. I remember writing to my mother and my uncle that they were guilty of “murder most foul as in the best it is; but this most foul, strange and unnatural”.

I lay weight upon this episode because my attitude, as I remember it, seems incompatible with my general spiritual life of the period, as will appear later.

I was genuinely fond of my Aunt Ada. She was womanly in the old-fashioned sense of the word; a purely passive type. Naturally talented though she was, she was both ignorant and bigoted. In her situation, she could not have been anything else. But her opinions did not interfere with her charity. A woman of infinite kindness. Her health was naturally delicate; an attack of rheumatic fever had damaged her heart and she died before her time. The meanness and selfishness of my Uncle Tom were principally responsible. He would not engage a secretary; he forced her to slave for the Scripture Union and it killed her.

One anecdote throws a curious light upon my character in these early days and also reveals her as possessed of a certain sense of humour. Some years before, on the platform at Redhill with my father, I had seen on the bookstall Across Patagonia by Lady Florence Dixie. The long name fascinated me; I begged him to buy it for me and he did. The name stuck and I decided to be King of Patagonia. Psycho-analysts will learn with pleasure that the name of my capital was Margaragstagregorstoryaka. “Margar” was derived from Margaret, queen of Henry VI, who was my favourite character in history. This is highly significant, as indicating the type of woman that I have always admired. I want her to be wicked, independent, courageous, ambitious, and so on. I cannot place the “ragstag”, but it is probably euphonic. “Gregor” is, of course, my cousin; “story” is what was then my favourite form of amusement. I cannot place the “yaka”, but that again is probably euphonic.

I cannot imagine why, at this very early age, I cultivated a profound aversion to, and contempt for, Queen Victoria. Merely, perhaps, the clean and decent instinct of a child! I announced my intention of leading the forces of Patagonia against her. One day my Aunt Ada took me to tea at Gunters'; and an important-looking official document was handed to me. It was Queen Victoria's reply. She was going to blow my capital to pieces and treat me personally in a very unpleasant manner. This document was sealed with a label marked with an anchor to suggest naval frightfulness, taken for this purpose from the end of a reel of cotton. But I took the document quite seriously and was horribly frightened.

The dinginess of my uncle's household, the atmosphere of severe disapproval of the universe in general, and the utter absence of the spirit of life, combined to make me detest my mother's family. There was, incidentally, a grave complication, for my father's death had increased the religious bigotry of my mother very greatly; and although she was so fond of her family, she was bound to regard them as very doubtful candidates for heaven. This attitude was naturally inexplicable to a child of such tender years; and the effect on me was to develop an almost petulant impatience with the whole question of religion. My Aunt Ada was my mother's favourite sister; yet at her funeral she refused to enter the church during the service and waited outside in the rain, only rejoining the procession when the corpse repassed those accursèd portals on its way to the cemetery. She stood by the grave while the parson read the service. It was apparently the architectural diabolism to which she most objected.

There was also an objection to the liturgy, on numerous grounds. It seems incredible, but is true, that the Plymouth Brethren regarded the Lord's Prayer as a “vain repetition, as do the heathen”. It was forbidden to use it! ! Jesus had indeed given this prayer as an example of how to pray; but everyone was expected to make up his own supplications ex tempore.

The situation resulted in a very amusing way. Having got to the point of saying. “Evil, be thou my good,” I racked my brains to discover some really abominable crimes to do. In a moment of desperate daring I sneaked one Sunday morning into the church frequented by my Uncle Tom on Streatham Common, prepared, so to speak, to wallow in it. It was one of the most bitter disappointments of my life! I could not detect anything which satisfied my ideas of damnation.

For a year or two after my father's death my mother did not seem to settle down; and during the holidays we either stayed with Bishop or wandered in hotels and hydros. I think she was afraid of bringing me up in London; but when my uncle moved to Streatham she compromised by taking a house in Polwarth Road. I hated it, because there were bigger houses in the neighbourhood.

I am not quite sure whether I am the most outrageous snob that ever lived, or whether I am not a snob at all. The truth of the matter is, I think, that I will not acquiesce in anything but the very best of its kind. I don't in the least mind going without a thing altogether, but if I have it at all it has got to be A1. England is a very bad place for me. I cannot endure people who are either superior or inferior to others, but only those who, whatever their station in life, are consciously unique and supreme. In the East, especially among Mohammedans, one can make friends with the very coolies; they respect themselves and others. They are gentlemen. But in England the spirit of independence is rare. Men of high rank and position nearly always betray consciousness of inferiority to, and dependence upon, others. Snobbishness, in this sense, is so widely spread that I rarely feel at home, unless with a supreme genius like Augustus John.

Aubrey Tanqueray is typical. He must not forfeit the esteem of his “little Parish”, and avoids mortification by shifting from one parish to another. When Paula asks him. “Do you trouble yourself about what servants think? he answers, “Of course.” If one had to worry about one's actions in respect of other people's ideas, one might as well be buried alive in an ant-heap or married to an ambitious violinist. Whether that man is the Prime Minister, modifying his opinions to catch votes, or a bourgeois in terror lest some harmless act should be misunderstood and outrage some petty convention, that man is an inferior man and I do not want to have anything to do with him any more than I want to eat canned salmon. Of course the world forces us all to compromise with our environment to some extent, and we only waste our strength if we fight pitched battles for points which are not worth a skirmish. It is only a faddist who refuses to conform with conventions of dress and the like. But our sincerity should be Roman about things that really matter to us. And I am still in doubt, as I write these words, as to how far it is right to employ strategy and diplomacy in order to gain one's point. The great men of the world have stood up and taken their medicine. Bradlaugh and Burton did not lose in the end by being downright. I never approved the super-subtlety of Huxley's campaign against Gladstone; and as for Swinburne, he died outright when he became respectable. Adaptation to one's environment makes for a sort of survival; but after all, the supreme victory is only won by those who prove themselves of so much hardier stuff than the rest that no power on earth is able to destroy them. The people who have really made history are the martyrs.

I suppose that there comes to all of us only too often the feeling which Freud calls the Œdipus complex. We want to repose, to be at peace with our fellows whom we love, who misunderstand us and for whose love we are hungry. We want to make terms, we want to surrender. But I have always found that, though I could acquiesce in some such line of conduct, though I could make all preparations for accommodation, yet when it came to the point, I was utterly unable to do the base, irrevocable act. I cannot even do evil that good may come. I abhor Jesuitry. I would rather lose than win by strategem. The utmost that I have been able to manage is to consent to put forward my principles in a form which will not openly outrage ordinary susceptibilities. But I feel so profoundly the urgency of doing my will that it is practically impossible for me to write on Shakespeare and the Musical Glasses without introducing the spiritual and moral principles which are the only things in myself that I can identify with myself.